By Dr. Ben Markham

May 5, 2020

The islands of St. Thomas, St. Croix and St. John are surrounded by Puerto Rico—once a Spanish colony—and the British Virgin Islands. Between the early eighteenth century and the early twentieth, the three main islands, combined with smaller minor islands in the surrounding archipelago, formed a single Danish colony: the Danish West Indies. In March 1917, sovereignty over the Danish West Indies was transferred from Denmark to the United States. This was because the Americans had purchased the islands for $25 million (the most they had ever spent on new territory) and, in doing so, created the territory of the US Virgin Islands. It was to remain an “unincorporated” territory, which meant that, although subject to the power of the US Congress, citizens of the islands were not necessarily granted the same rights under the US Constitution as those on the American mainland. Moreover, statehood was not the ultimate goal. The acquisition of the islands was not expansion for settlement; it was expansion for strategic advantage. This was to impact the islands’ development in the future as they were left behind in favor of the newer portions of the continental United States.

In the context of the ongoing First World War that was raging elsewhere, the US purchase of the Danish West Indies—far from the Fronts—might be considered a somewhat marginal event. But it is nonetheless significant. Indeed, the purchase was more than simply a financial and territorial transaction. Rather, it revealed the trajectories of three different early-twentieth century empires: those of Denmark, Great Britain and the United States. For Denmark, the least powerful of the three, it meant the end of the Danish Empire outside of the North Atlantic and Arctic Oceans. (Another of Denmark’s islands, Iceland, had also begun to pull away during this period.) For the British, the purchase was proof of the decline of their influence in the Caribbean. As for the Americans, this was the last in a string of territorial acquisitions outside of the contiguous United States that had begun in the mid-nineteenth century. Alaska, the Midway Islands, Hawaii, the Philippines, American Samoa, Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Panama Canal Zone had all been brought under American control. By the mid-1910s, this had spread further into the Caribbean as Haiti and the Dominican Republic, too, were under American military occupation. The purchase of the Danish West Indies signified the continued rise of the United States as a global power at the expense of other European empires.

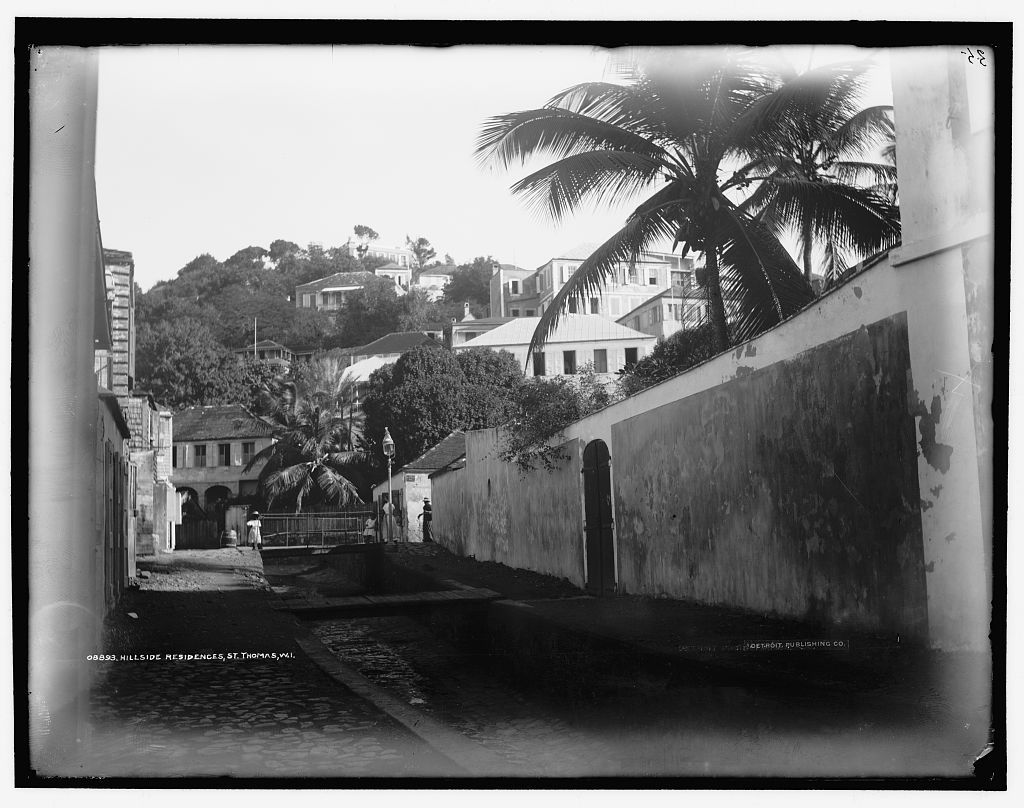

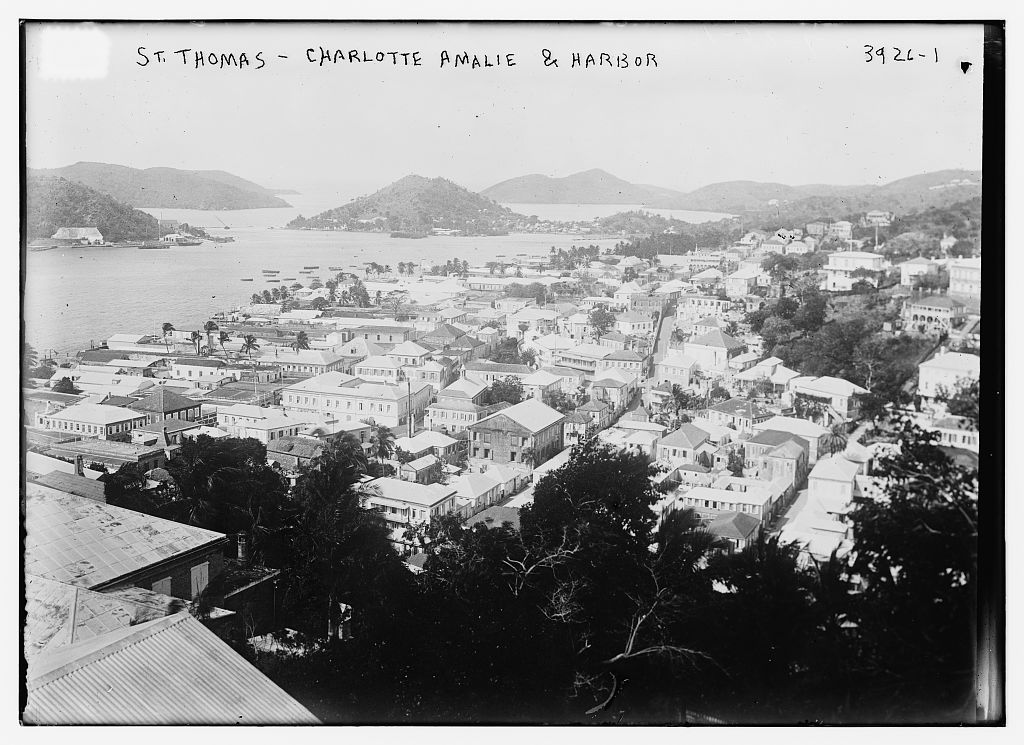

This was a process long in the making. The United States first expressed an interest in obtaining control of the islands as early as the immediate post-Civil War era. In 1866, the US Secretary of State, William H. Seward, toured the Caribbean and was struck by the strategic potential of the region, particularly the natural harbor located at St. Thomas. Shortly after Seward’s tour the United States offered to purchase the Danish islands, but the offer became mired in Senate proceedings and was eventually dropped, much to the irritation of the Danes. The United States did end up buying land during this period, though: the much larger territory of Alaska, acquired from Russia for $7.2 million in 1867.[1]

A second attempt to purchase the islands was made in the 1900s, at what might be considered to be the height of American expansion beyond the confines of the North American continent. In the wake of the Spanish-American War, the United States tightened its grip on the Caribbean region, taking control of Puerto Rico and establishing itself as the sole influential power in the former Spanish colonies of Cuba and Panama. This was also the moment that the United States seized the Philippines, Guam and American Samoa in the Pacific. These acquisitions represented the creation of a new form of American control, of which race was a defining factor. These were not territories whose acquisition catalyzed a wave of white settlement and statehood. Puerto Ricans, Panamanians, Filipinos, the Chamorros of Guam, and Samoans were considered racially inferior and incapable of self-government, let alone incorporation into the Union.[2] They were instead all brought under varying forms of military occupation as strategic outposts rather than further fulfilments or extra-continental extensions of Manifest Destiny. The Danish West Indies were to be viewed in a similar way. In the midst of this vast American expansion at the turn of the century, the future of the Danish islands once again came under discussion. In 1902, with the backing of a now more enthusiastic US legislature, another offer was made to Copenhagen. This time, in contrast to their 1860s-stance, it was the Danes who were reluctant, as they still hoped to reignite the islands’ economic fortunes.

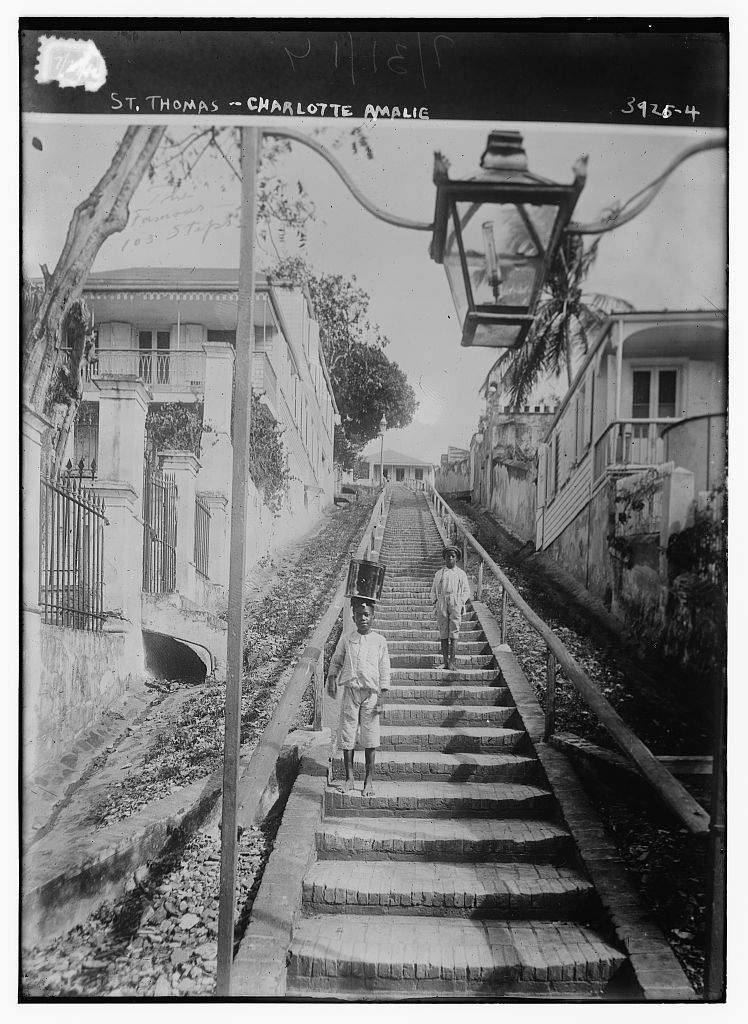

But, by the outbreak of the First World War, it was becoming increasingly clear that Denmark could no longer afford to maintain its small Caribbean colony. Sugar exports from the islands to Denmark had dropped dramatically, and the combined deficit of the islands averaged annually at $22,470 in the period between 1910 and 1917.[3] Denmark’s influence was clearly waning. Only a very small Danish population lived on the islands, the Danish language was hardly spoken, and the Spanish Alfonso—not the Danish Krøne –functioned as the currency in circulation (a legacy of the Spanish domination of the Caribbean in the eighteenth and early-nineteenth centuries). This dire situation reopened the possibility of the sale of the islands.

The US attraction to the islands remained largely the same as it had been for the last half-century or so. First, the acquisition of the Danish West Indies, it was hoped, would solidify American entry onto the world stage as an imperial—or quasi-imperial—power.[4] Second, the islands’ location was deemed to be ideal for the location of a new naval base. A US-controlled chain of islands from Puerto Rico to St. Croix could make certain the defense of American interests and, if necessary, of the mainland. The US Navy would have ready access to any part of the Caribbean, while being able to launch easily into either the Atlantic or Pacific Oceans, via the Panama Canal in the case of the latter.

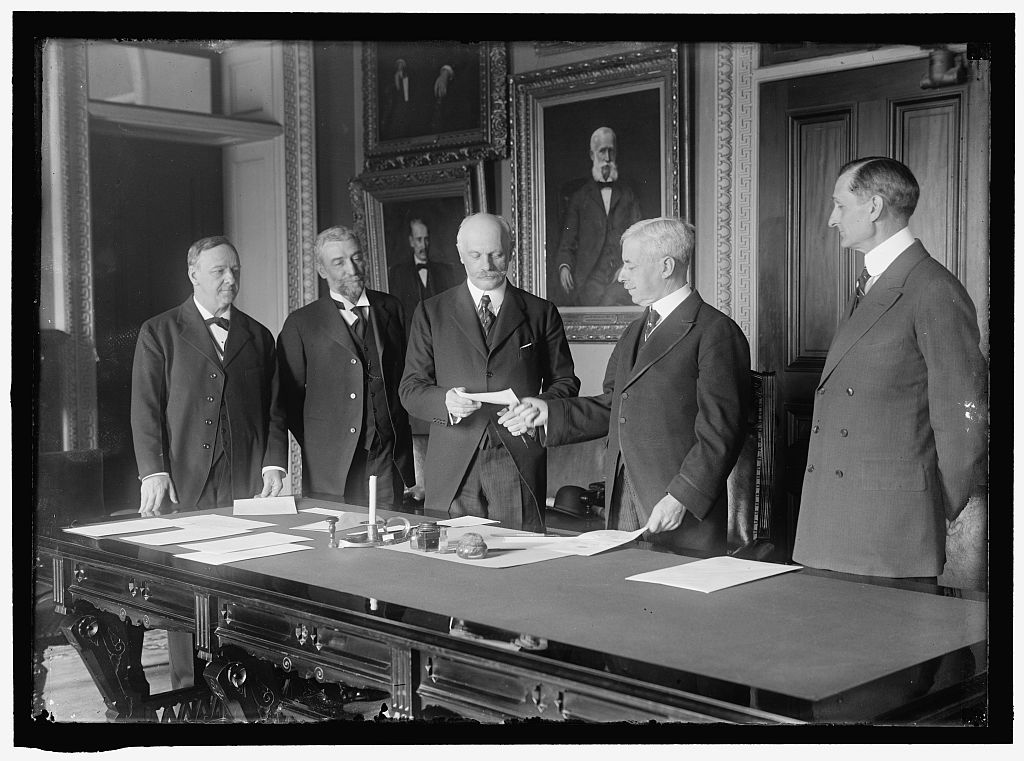

The third reason, while undoubtedly important in the past, was perhaps the most potent in the context of the First World War. This was a concern regarding the presence of other European powers in the Caribbean region. By the 1910s, this concern was focused primarily on one country: Germany. In hindsight, this may seem something of an over-exaggeration of the German threat to the Caribbean. The American worry, however, was that if Germany overran neighboring Denmark, this would bring the islands under German occupation as well.[5] In order to see off this potential threat, the Danish and the Americans negotiated a sale that was to the satisfaction of both parties, having been approved by referendum in Denmark and ratified by both nations in January 1917. As a result, Denmark was able to relinquish a colony it could no longer sustain, and the United States strengthened further its influence in the Caribbean.

The other major power in the Caribbean during this period was Great Britain, which was in possession of several islands around the region, the closest to the Danish West Indies being the British Virgin Islands, Anguilla, and St. Kitts. The proposed redistribution of territorial control in the Danish archipelago was watched closely between 1916 and 1917. In London, The Times reported the sale with disappointment at what it saw as a missed opportunity, particularly in the wake of the opening of the Panama Canal. The “complex civilization of the modern world,” noted one article, “rests upon the productions of the tropics to a much greater extent than is generally realised….The United States were quicker to see this than we [i.e. Britain] were, and have just proved that they saw it by purchasing the Danish West Indies.” The article went on to remark that, through the purchase, the United States had gained significant strategic and economic advantages in the Caribbean.[6] The British, meanwhile, were being left behind.

The reaction among British officials concerned with imperial and foreign affairs, however, appears to have been minimal. In contrast to the stance of The Times, the sale of the islands was viewed with satisfaction. The Danish deal with the United States ensured that the this strategic territory would not fall into the hands of Germany, with whom the British were, of course, currently at war. There was, nevertheless, a palpable sense that the sale had highlighted the fact that British influence in the Caribbean region was clearly in decline.[7] Indeed, in the midst of the First World War, Britain simply did not have the resources to reassert itself in the Caribbean; the Danish islands were most certainly out of their reach. In 1916, during the negotiation phase of the purchase, the British Foreign Office noted to the British Minister to Copenhagen that US control of the islands was preferable as “we could never in any case acquire them for ourselves.”[8] A challenge to the US purchase and the spread of American territorial control was also regarded as being out of the question. Again, the resources to do so simply were not there. Britain’s war effort relied too heavily on American trade and goodwill to be risked for a few islands thousands of miles from the Front.[9] The Foreign Office remarked, “It would be impossible for us to prevent it and most impolitic to do so.”[10] The 1916-17 sale of the Danish West Indies, then, demonstrates British retrenchment from a traditional region of influence in favor of the United States.[11] Such were the contemporary perceptions of British imperial decline, and growing American strength, that it was not considered feasible for the sale to have gone any other way.

The American flag was raised over Charlotte Amalie on the island of St. Thomas in March 1917, thus bringing the now-former Danish West Indies under US rule. But the transfer also forced the islands into constitutional uncertainty. Initially, administration of the islands was entrusted to the President of the United States directly. In light of the strategic significance of the islands, this was soon altered, with administrative responsibility delegated instead to naval governors appointed by the President (similar to systems that had been put in place in Guam and American Samoa). The hopes of the 26,000 resident Islanders—the vast majority of whom were African American—that the purchase would solve the islands’ ongoing socio-economic difficulties were soon dashed. Institutional racism was rife, government investment was minimal, and the status of the US Virgin Islands as an unincorporated territory of the United States was not even formalized until 1927, ten years after the transfer of power.[12]

Nevertheless, the purchase of the Virgin Islands by the United States was diplomatically significant, as it represented the cementation of American dominance over the Caribbean. While the transaction had been an entirely Danish-American affair, it nonetheless had a notable effect on British perceptions of its own role in the Caribbean. Indeed, the purchase ensured that the Anglo-American balance of power in the region, long in the making, had shifted in favor of the United States for good. For the islanders themselves, American rule did little to change the status quo, as development was impeded by indifference and racism. The islands were treated merely as a colonial backwater or, at best, a glorified naval base. It was not until decades after the purchase that the US Virgin Islands were revitalized as a center for tourism and other light industries and granted a greater degree of self-governance. The purchase of the US Virgin Islands was a symbol of American regional power and interest in further expansion, but the years afterward were to reveal a fundamental American disinterest in its own colonial acquisitions. The US Virgin Islands constituted the final territory to be purchased by the United States from another country.

Dr. Ben Markham

Ben Markham was awarded his PhD in History by the University of Essex in 2017. He has written and delivered several papers on the theme of Anglo-American relations in the early twentieth century. He teaches history at Plume, Maldon's Community Academy in Essex, UK.