By Dr. Chelsea Gibson and Dr. Kenyon Zimmer

January 13, 2025

Below is an interview with Dr. Kenyon Zimmer, a historian of transnational radicalism. Recently, as I was editing a piece for our blog, I stumbled across his personal website where he has published a comprehensive digital archive of Red Scare deportees. I thought our readers could benefit from this resource, both for their own research and for the classroom. It is also a wonderful example of a digital history project, and Zimmer gives us insight into the surprising responses he’s had to it. If you would like us to highlight any other digital projects, please reach out to me at chelsea.gibson@binghamton.edu!

Could you briefly describe your project?

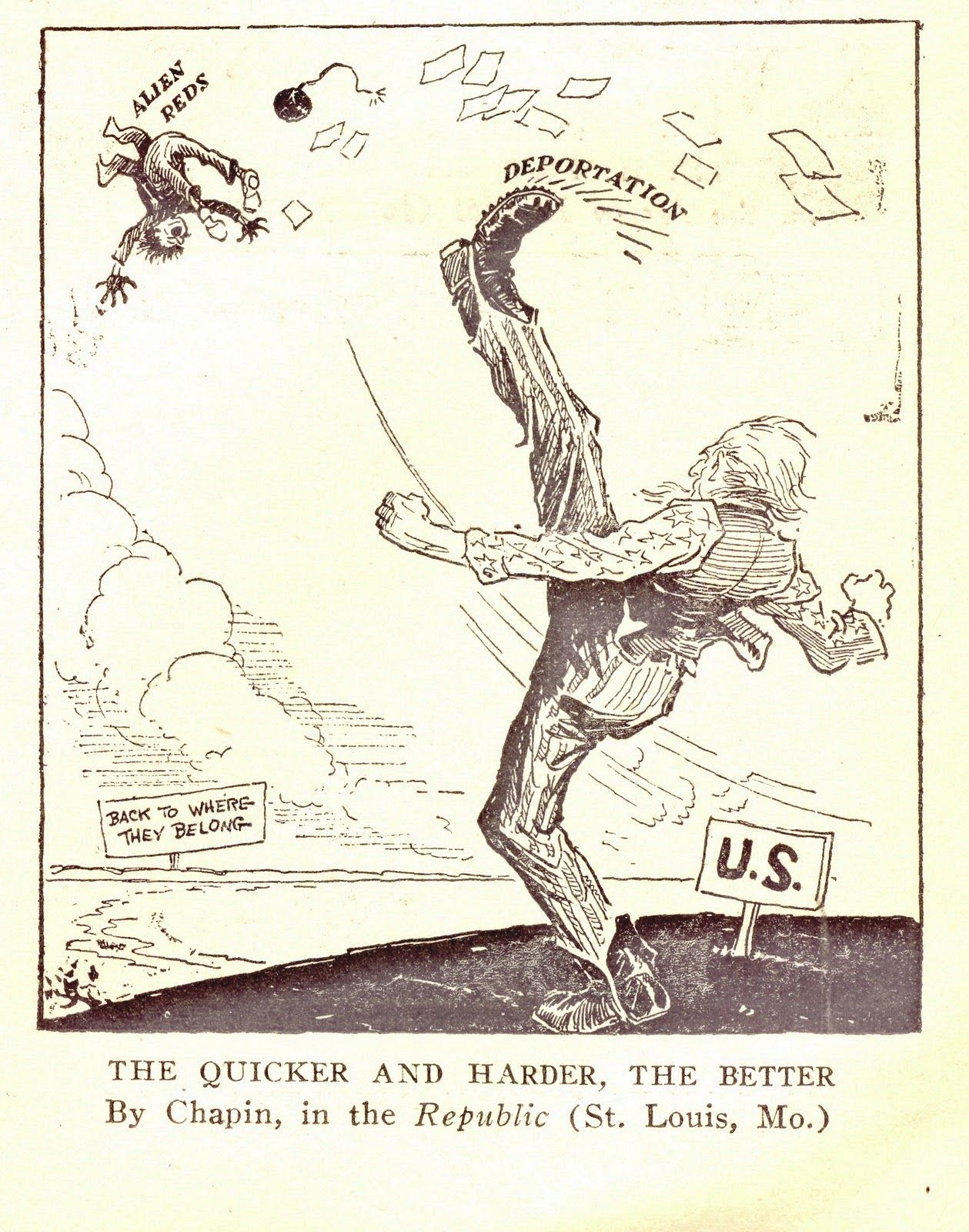

The website is a compilation of biographical profiles of immigrant radicals who were deported from the United States as part of the federal government’s antiradical campaign during and after the First World War, between 1917 and 1925. It currently includes information on 835 individuals, out of an approximate total of a thousand Red Scare deportees.

What is your research on and how did it lead you to become interested in these deportees?

This online project grew out of my research for a book that I am currently writing about the Red Scare deportees and their transnational trajectories, connections, and impacts. The book examines the First Red Scare and deportation from the perspective of the deportees themselves, and begins, rather than ends, with their expulsion from the United States.

This topic emerged out of earlier research of mine, including my book Immigrants against the State: Yiddish and Italian Anarchism in America (2015) and articles I have published on American anarchist volunteers in the Spanish Civil War of 1936-1939. In both cases, I repeatedly encountered Red Scare deportees in the sources and included them in my narratives. As someone trained in both transnational history and migration history, I was alert to the fact that these individuals’ stories didn’t stop at national borders, and that their involuntary migrations served to link historical events in different locations. Eventually I realized that there was more than enough material about this cohort of radical deportees to literally fill a book, and that such a book could fundamentally reframe how we view the First Red Scare. It will also contribute to the new field of the history of deportation and, I hope, help lay the foundations for future research on the history of deportees themselves.

Where did you find the information?

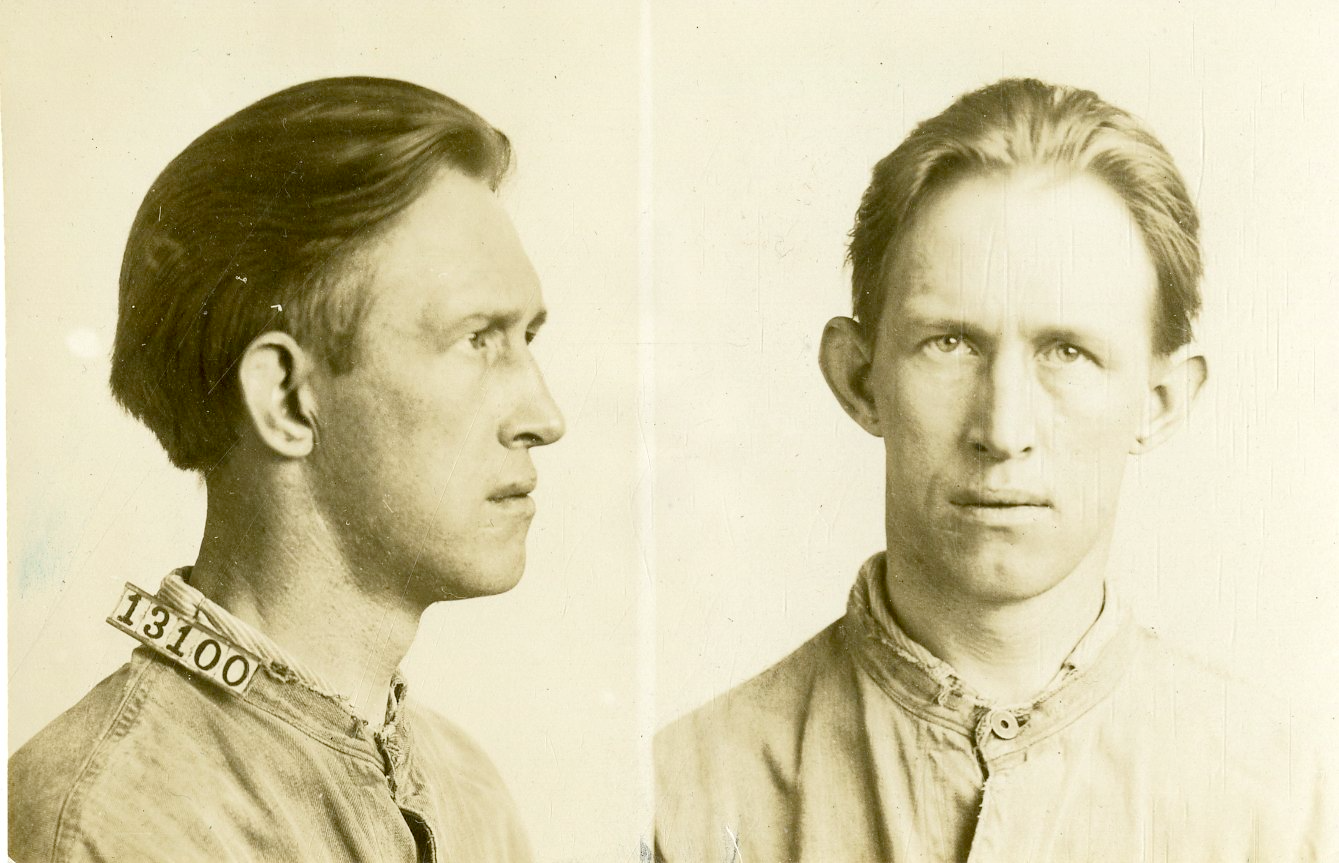

Anywhere and everywhere that I could! It turns out that no government agency at the time, and no historian since, ever compiled a comprehensive list of the Red Scare deportees, let alone studied them as a group. So even compiling the list of names to research was difficult, and involved searching through congressional hearings, records of both the Bureau of Investigation and the Bureau of Immigration, ship passenger manifests, commercial and radical periodicals, memoirs of people involved, and anything else I could find. My initial effort yielded around 500 names, which over the course of several years has grown to 835.

The next step entailed tracking down biographical information about each named person, including details about their political activities in the United States and their deportations. The most useful sources were usually their case files from the Bureau of Immigration at the National Archives, of which I have located and copied around 700. I also searched digitized Bureau of Investigation files (at website fold3.com), mainstream newspapers (at newspapers.com and the Library of Congress’s Chronicling America project), digitized and microfilmed radical periodicals, and relevant archives like the Joseph A. Labadie Collection at the University of Michigan and the Industrial Workers of the World Collection at Wayne State University. Finally, in a few cases I was able to track down and interview descendants of deportees.

The most challenging (and rewarding) research involved tracing individuals’ lives and activities after their deportations, which I’ve been able to do for about 20 percent of the deportees. Much of this relies on records of government surveillance that are accessible in state archives in countries like England and Italy, in digitized labor and radical newspapers from the countries involved, and, in the case of Russia, collaboration with a number of researchers in Eastern Europe with access to relevant knowledge and documents. It is worth adding that much of this would not be possible without the digitization of thousands of relevant sources, or without the aid of a number of research assistants and translators I have worked with (some of whom generously donated their skills, and others of whom I have paid out of my own pocket). In many ways, this has been the most collective endeavor of my academic career!

What made you want to publish this information online?

Initially, I mostly thought that posting the profiles might be a useful method for compiling and synthesizing the research that I had accumulated up to that point, allowing me to see the larger patterns of the deportee experience and find the most interesting stories to pursue for the book. Then COVID-19 hit, and I had to cancel further research trips, which led me to focus on completing the online profiles and developing the website as a more polished and public-facing resource. My notion was (and remains) that two main groups of people might find it useful: those interested in or doing research on the history of the American Left, and relatives and descendants of individual deportees conducting genealogical research.

I also, almost as an afterthought, added a note to the project’s homepage asking anyone who spotted an error or had more information about profiled individuals to contact me. To my surprise, a considerable number of people have reached out to me through the website since I first began posting profiles in early 2020. Some have been other scholars whose research touched upon certain figures, but most have been descendants of deportees either offering or asking for additional information about their relatives. I have freely shared copies of documents with those asking for them—many of whom were learning for the first time of their family’s radical past—while several others have generously shared invaluable documents and personal details with me about deportees and how the Red Scare affected their families. The website has therefore turned out to be an incredible, if unexpected, source of additional research material.

Is there a particular story that you find interesting or noteworthy?

So many! Too many, really. To give just a few examples: The deported IWW member who became the most powerful union leader in Finland. The Italian anarchist who was one of the first foreign volunteers killed in the Spanish Civil War. The English Communist who published an influential book of the menace of “Americanism.” The Russian Jewish anarchist who co-founded the first Yiddish newspaper in Mexico City. The German IWW member who became a highly effective underground agent of the Communist International’s international communications network. The Italian anarchist couple whose four American-born children remained behind and never spoke of their parents’ politics or deportation, even with their spouses. The four deported radicals who were later elected to national office in their respective countries (Italy, Finland, Ireland, and Spain). The surprising number of deportees who secretly returned to America and continued to carry out radical activities under assumed names. The Cuban anarchist poet who was allowed to legally return to the United States as an anti-Castro dissident in the 1960s.

I could go on and on—which is making the writing of the book challenging, though the existence of the website at least ensures that the stories and examples that don’t make it into the manuscript are not lost or forgotten.

Do you have any advice for scholars who are interested in making a digital archive in this vein?

Don’t be afraid to have it be a work in progress (which mine very much still is). Expect it to take a lot of time and effort. And encourage users to contact you—they can be an important resource to you, and vice versa!

What do the stories of these radicals help us better understand about the long Progressive Era?

These deportees and the movements they belonged to—anarchism, socialism, Communism, and the IWW—represented an insurgent counterpoint to Progressivism. They were motivated by the same “social problems” as the Progressives but arrived at much more radical conclusions, and they were ultimately victims of the Progressive Era’s expansion of state capacity and social control. Yet their stories did not end with deportation. If American Progressivism was, as Daniel Rodgers famously argued, a transnational result of “Atlantic crossings,” then the political deportations carried out under Woodrow Wilson’s Progressive administration represent a series of Atlantic crossings in the other direction: Deportation unintentionally disseminated “American” radicals and radical ideas throughout Europe (and beyond), and the transnational connections of the deportees continued to influence radical and labor movements on both continents throughout the interwar period.

If people want to add information to the collection, how should they contact you?

The website has a message submission page, but people are also welcome to email me at kzimmer@uta.edu.