By Dr. Theresa Ventura

February 19, 2020

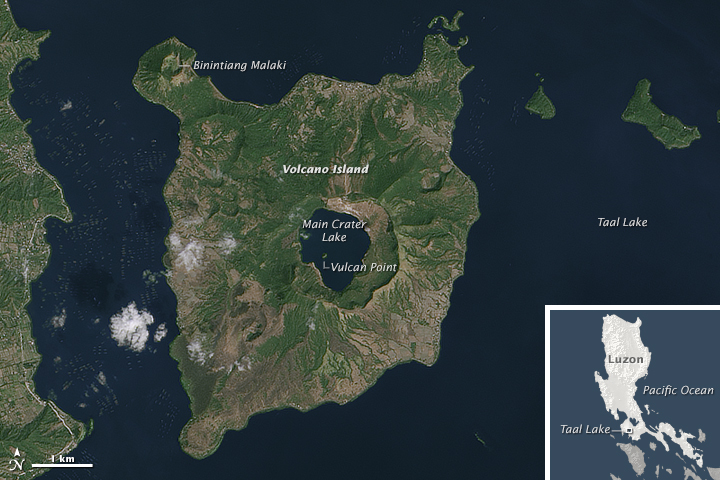

Taal Volcano crowns an island in the middle of Lake Taal in Southern Luzon. Its wide-mouthed cone is filled with water, giving Taal the Ripley’s Believe It or Not distinction of containing the largest lake on an island in a lake that is also on an island. Taal also has the distinction of being the second most active volcano in the Philippines. We were reminded of that destructive power when it began to show signs of an eruption on the morning of January 12, 2020. The Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology (PHIVOLCS) issued a level four out of five alert, mandating an evacuation of the area. In a matter of days, nearly 30,000 people within a nine-mile radius moved to safety, including the 6,000 living on Taal Island. Photographers arrived and captured the chaos of the evacuation, the devastation of homes blanketed in ash, and the arresting beauty of volcanic lightning storms. Such images also brought empathy and an international outpouring of donations. The week revealed the terror of an eruption, the ways in which local communities mobilize care, and the political outrage that follows when the federal state appears slow to respond, as was the case with the already contentious Duterte administration. The 2020 eruption also allows us to reflect on the politics of disaster, the press, and state obligation during Taal’s deadliest eruption in the Progressive Era.

When Taal erupted in January of 1911 the Philippines were the largest overseas colony of the United States. Residents on what was then called Bulkan ng Isla—Volcano Island—awoke to a strong earthquake on January 27. With quakes common and no official notice to evacuate, many decided to stay in place. But three days later Taal exploded in an outburst audible over an area 360-kilometers in diameter. For one week, the volcano spewed a four-kilometer high column of burning mud, iron salts, sulfur, and carbon dioxide. Taal Lake contracted before crashing onto the opposite shore in a volcanic tsunami that reached 762 meters inland. The receding waters dragged people, homes, and animals on its return to the lake bed. Bulkan ng Isla, wrote an observer, “was devastated, not a blade of grass escaping,” and an estimated 1200-2000 people lost their lives.[1] As Taal quieted, a new storm over the American response brewed.

In contrast to the wide circulation of today’s empathy-invoking photographs, Taal’s 1911 eruption barely registered in US mainland media. The inattention was an artifact of colonialism. Formally annexed in 1899, the Supreme Court ruled in 1901 the Philippines were foreign [to the US] in a domestic sense.” The verdict rendered Filipinos, along with Puerto Ricans, “non-citizen nationals.” As American subjects, they bore allegiance and responsibilities to the American government, including military service. But as “non-citizens,” they were denied the full privileges and protections of citizenship, not the least of which was a vote in federal governance. The nationalist paper El Ideal captured what it meant to belong to yet remain separate from the United States in an editorial condemning American “passivity in the disaster.” Mainland disinterest was due “in part, to the fact that the dead and wounded are only Filipinos. If the tragedy had occurred elsewhere in the United States and the Government had show[n] the same attitude the roar of indignation of the people would have made the White House tremble on its foundations.”[2]

The on-the-ground relief, moreover, demonstrated the difficulties of conducting a rescue mission during an extended military occupation. The Philippine Constabulary—a militarized island-wide police force led by Americans and composed of American and Philippine recruits—was the one state institution with the capacity to organize a coordinated response. Units were already in Southern Luzon when Taal erupted. But the Constabulary’s response was hindered by its well-deserved reputation as an agent of state repression. It guarded tax collectors, forcibly transferred suspected lepers from their communities, and made arrests for everyday practices like gambling and opium taking. The Constabulary policed agricultural workers suspected of breaking work contracts or reneging on debt, and it retained the legal power to resettle entire barrios suspected of harboring thieves. When the Constabulary finally reached Taal, survivors fled. Officers returned the mistrust; as one American later recalled, his superior assumed fleeing survivors were “robbing the dead in the stricken district.”[3] Far from organizing a rescue, the Constabulary devoted time and resources to investigating suspected cases of theft. The Red Cross disbursed its funds to a former US soldier turned Taal tour guide named JD Ward. Ward charged P2500 for the use of his bancas (small boats), a fee La Vanguardia called “stupendous!”[4] Adding insult to injury, Ward “dash[ed] aimlessly around the lake,” refusing to transport the injured and fulfill his contractual obligation “because there were American women aboard the launch.”[5] Inasmuch as Americans in the Philippines paid attention to the tragedy, they appear to have done so as disaster tourists.

Subsequent press criticisms built on and extended longer-standing criticisms of US rule and in the process articulated what I call “disaster nationalism.” Disaster nationalism presented a formidable challenge to at least three tenets of colonial rule. First, to the charge that the Philippines were too ethnically and linguistically diverse to constitute one nation, disaster nationalists turned Taal into a symbol of national unity. Its eruption, wrote the once pro-American El Ideal, was “an invisible thread, which united common interests and makes one those who were born under the same sky.” Volunteer-led recovery efforts, including the wearing of black armbands to commemorate victims, were proof that there was a Filipino “public spirit [that] in private and in social matters watches over its own.”[6]

Second, disaster nationalism rejected the motif of American colonialism as a schoolhouse. As scholars have noted, including most recently Sarah Steinbock-Pratt’s Educating the Empire, American imperialists cast their rule as training Filipinos in the art of democracy.[7] This logic was embedded in institutions such as the Philippine Assembly, an elected legislative body established in 1907 that acted as a lower house to the presidentially-appointed seven-member Philippine Commission. The majority-American Commission retained full veto power over legislation proposed by the majority-Philippine Assembly. Otherwise staid matters of budgeting were heated battles over stewardship and the right, as one patriotic organization charged before Taal’s eruption, to “properly prepare the budgets without killing the people with hunger.”[8] Following the eruption, Assembly members appropriated P100,000 for relief, which the Commission vetoed. La Democracia declared the veto to be proof that US Commissioners, “in the presence of a scene of misery and much tears which urgently require the sacrifice of the most rebellious self-love,” chose “to establish supremacy, to show power.”[9]

Third, disaster nationalism reclaimed the tropics from the racist environmental determinism of colonialists. To the charge that tropical heat disinclined Filipinos to work, disaster nationalists held the American response lazy. That two of the most powerful members of the Philippine Commission – Secretary of the Interior Dean Conant Worcester and Governor General W. Cameron Forbes – were on vacation when Taal erupted confirmed the allegation. Both were in Baguio, the soon-to-open summer capital nestled in the Cordillera Mountains. Rebecca McKenna’s American Imperial Pastoral shows how US fears of Manila’s tropical heat led administrators to build a temperate summer capital at great cost to a perpetually small colonial treasury.[10] Even Worcester admitted that the distance between upland Baguio and lowland Taal meant that “a period of several days elapsed before it was realized that an appalling calamity had occurred.”[11] For the nationalist paper La Vanguardia, both vacations in the mountains during summer and tours through the islands by boat in cooler weather indicated that “the clamor of the people has not reached the yacht on which the gentlemen of the payroll have just made a trip for pleasure and investigation. The music on board drowns the imprecations of the multitude which supports the state.”[12]

Finally, disaster nationalism turned an intimate knowledge of Philippine landscape into a criterion of governance. Experiential knowledge, rather than temperate winters, bestowed foresight. When the rice crop failed later in 1911, La Vanguardia asked “why did the Philippine Commission not foresee that the rice crop would one day not be sufficient equal to consumption?” (September 22, 1911). The ability to anticipate disaster required a state that managed its risks. Assembly members scored their biggest victory when they secured funding for the establishment of a seismologic monitoring station at the base of Taal. Jumping to 1982, the independent Philippine state grouped this station and others into PHIVOLCS, which has since played a crucial role in monitoring volcanic activity, mandating, and coordinating evacuations. Taal’s 1911 eruption would become the last of the twentieth century to have claimed more than 1,000 lives. May it stay that way through the twenty-first century.

The anticolonial disaster nationalism of the Progressive Era emphasized a point increasingly relevant in an age of climate crisis. The boundary between natural and human-made disaster was and remains porous. For Filipinos, Taal’s tragedy was compounded by the disaster of US colonialism. Its sting was felt in the disinterest shown by the mainland press, the mutual distrust between the Constabulary and local residents, and the political and symbolic battles over the relief. Today’s global outpouring of support, by contrast, points to the global reach of the Filipinx diaspora as well as the changed geopolitical realities of Philippine independence. However, and as many have noted, the Trump administration’s response to Puerto Rico in the aftermath of Hurricane Maria and the earthquakes of 2020—whether lecturing on budgets, denying relief, or tossing paper towels—throws the human costs of “foreign in a domestic sense” into stark relief.

Dr. Theresa Ventura

Theresa Ventura is an assistant professor of history at Concordia University, Montréal. She is completing a manuscript entitled,Empire Reformed: The United States, the Philippines, and the Practices of Development, 1898-1946, which places contests over natural resource management at the center of American overseas state building and power. She has held fellowships from the ACLS-Melon Foundation, the Library of Congress's John W. Kluge Center, and the Fonds de Recherche du Québec and has published inPhilippine Studies(2015),Agricultural History(2016),History and Technology(2019), and theJournal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era(forthcoming 2020).