By Brendan Hornbostel

August 29, 2023

This is part of a series of blog posts on crime and punishment in the Gilded Age and Progressive Era, covering histories of violence, law, criminal justice, and incarceration. Read the posts in this series here and find the CFP here.

As the capital of the United States, Washington, D.C., is a place overdetermined with meaning. Simultaneously a symbol for the nation and a longtime major Black city without political representation, Washington, D.C., has appeared to many—in the words of blues poet Gil Scott-Heron—as “a ball of contradictions” between affluent white political elites “who come and go” and the predominantly Black poor and working-class “who’ve got to stay.”[1] Historians have often tried to solve this paradox by separating histories of the federal government in Washington from those of metropolitan D.C. as the “city beyond the monuments.”[2] In doing so, however, these histories have obscured the intertwined development of Washington as the headquarters of U.S. state power and the longstanding Black metropolis of D.C. as a “captive colony.”[3] Perhaps nowhere is this entanglement better illustrated than the McMillan Plan’s Progressive-Era redesign of “Imperial Washington” made possible by the racialized slum clearance of the Metropolitan Police Department’s “war on alleys” at the turn of the twentieth century.[4]

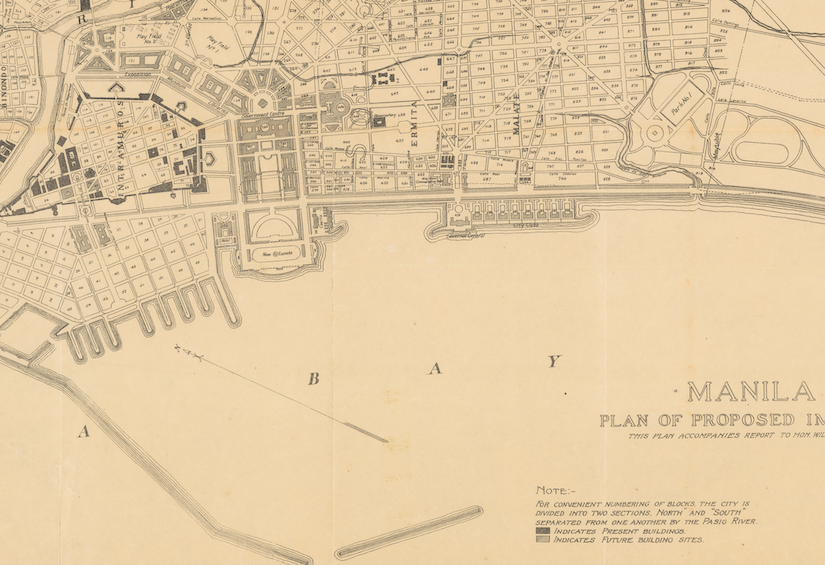

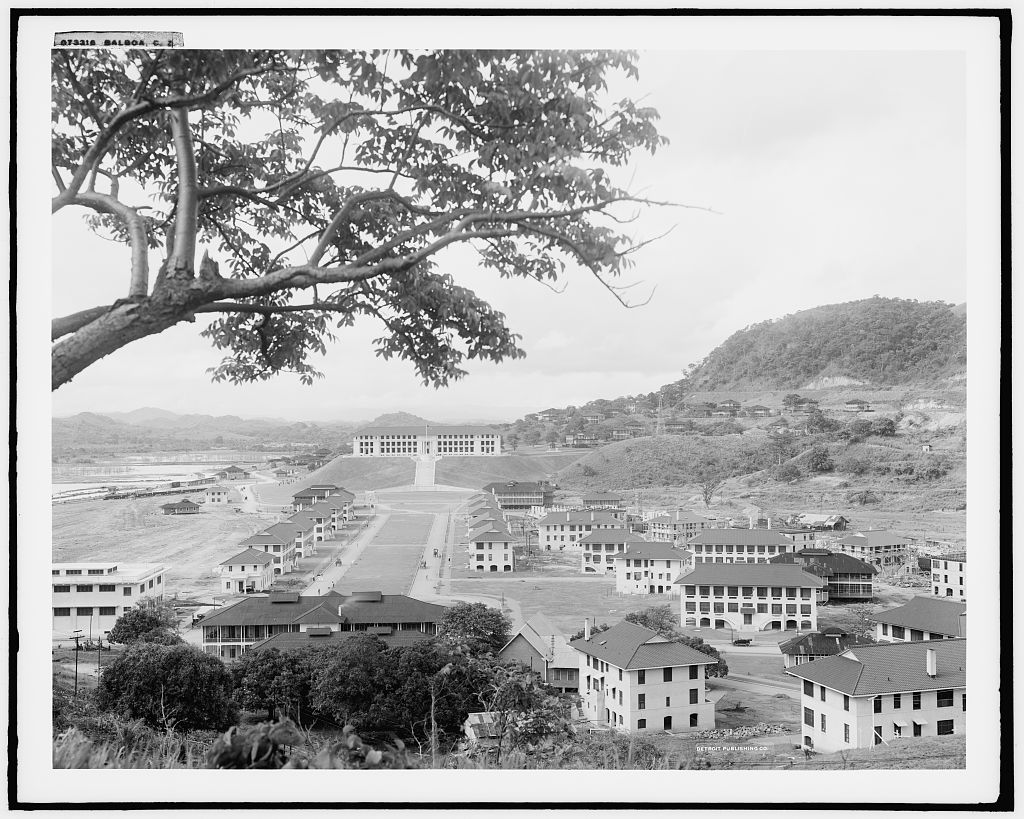

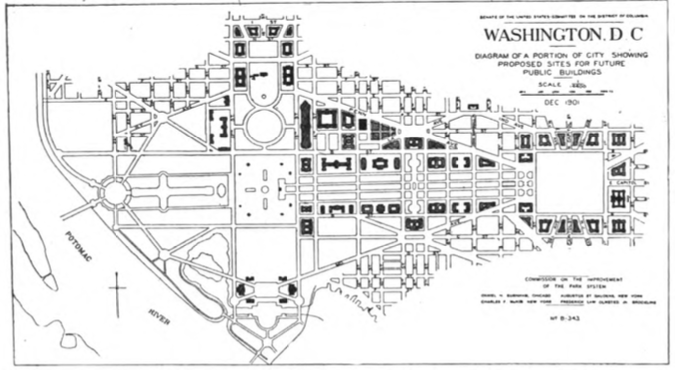

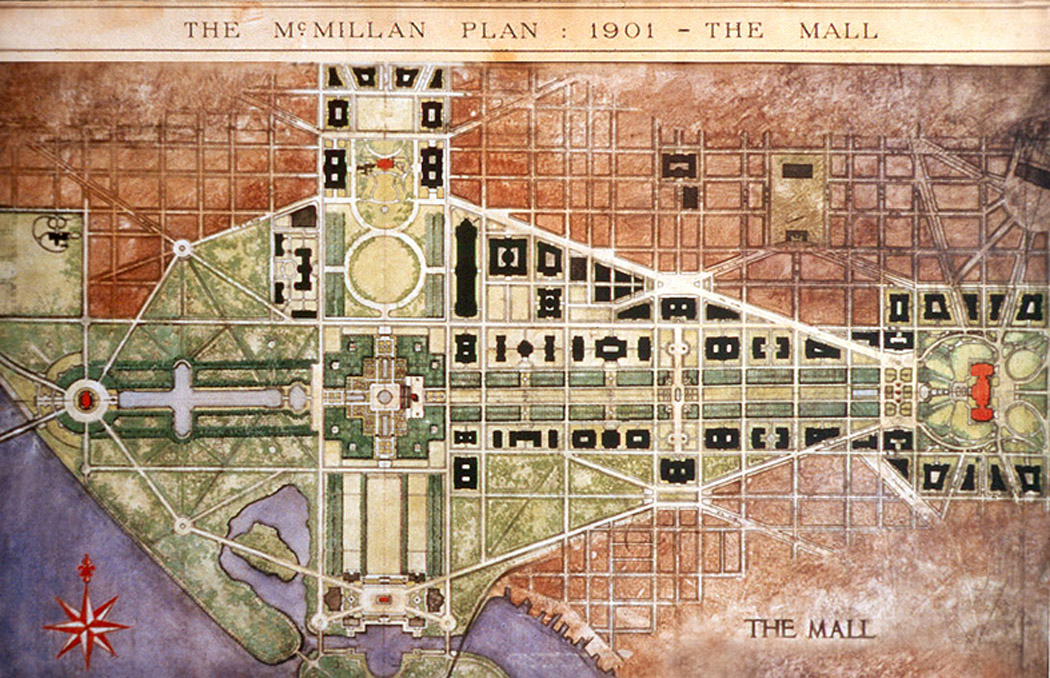

Emerging from the political dealings of Michigan Senator James McMillan, the Senate Park Commission’s 1902 report, “The Improvement of the Park System of the District of Columbia,” better known as the McMillan Plan, set the standard for the modern development of Washington.[5] Staffed by three of the most important architectural alumni of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition—Daniel Burnham, Charles McKim, and Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr.—the Commission’s McMillan Plan was an attempt, in the words of its secretary Charles Moore, to make “the ephemeral White City” of the Chicago world’s fair into an “Eternal City” in Washington.[6] In the wake of the 1898 Spanish-American War that founded a U.S. empire in the Pacific and Caribbean, the McMillan Plan not only catalyzed a national City Beautiful movement of urban planning, but importantly, presented downtown Washington as a “City Imperial” model for subsequent U.S. imperial development in the Philippines and the Panama Canal Zone (Figures 1-3).[7]

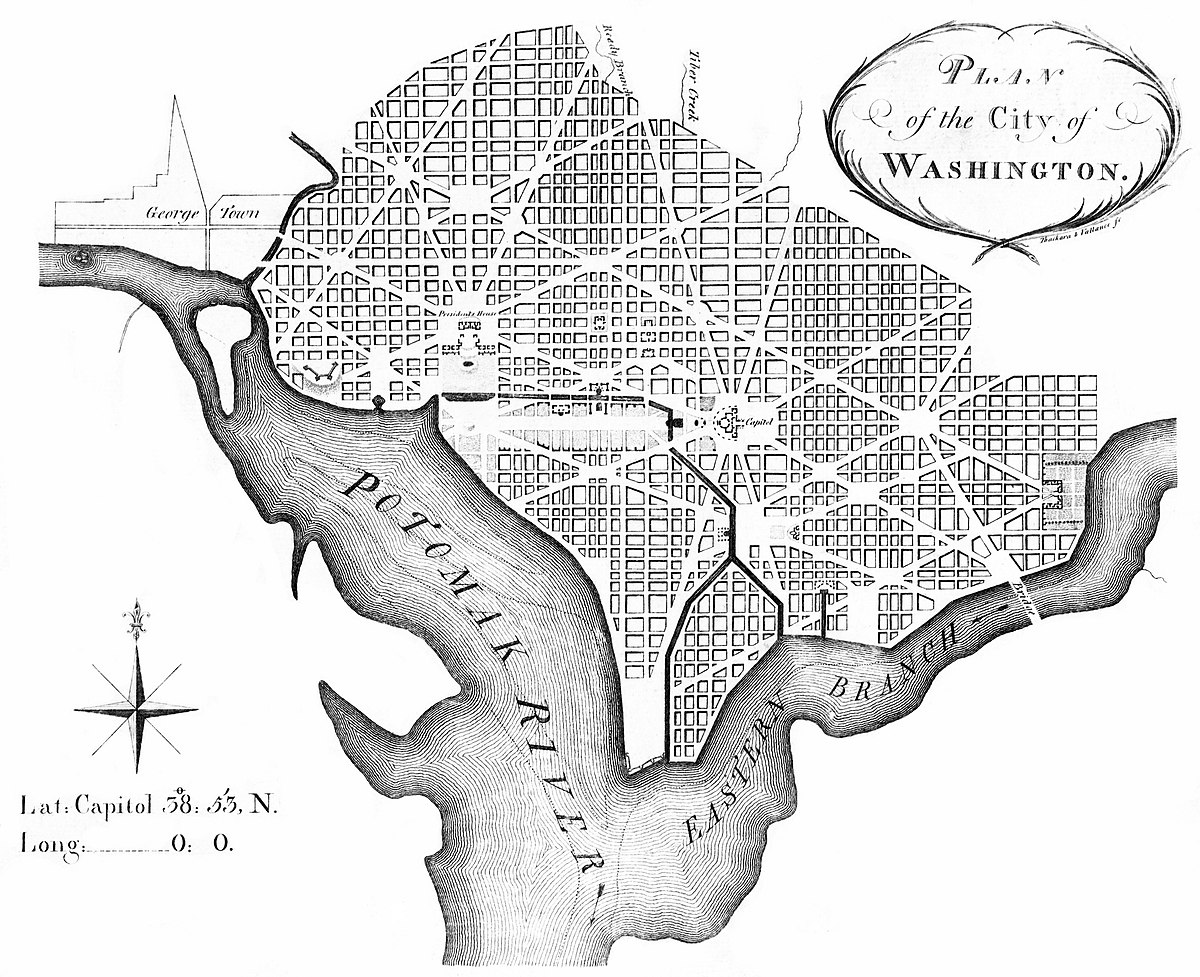

While the initial 1791 L’Enfant Plan had envisioned Washington as an architectural “microcosm” of the United States, with diagonal streets bearing the names of states radiating out to the city and the National Mall as a “Grand Avenue” embodying the balance of power between the Capitol and the White House, the McMillan Plan updated this architectural embodiment for the new U.S. empire (Figure 4).[8] In addition to its most celebrated achievements of Union Station and the Lincoln Memorial, the McMillan Plan envisioned housing the United States’ burgeoning imperial administration alongside the National Mall in what is today Federal Triangle and Federal Center (Figure 5). But standing in the way, quite literally, of the McMillan Plan, were the mostly poor and working-class Black neighborhoods of Murder Bay along Pennsylvania Avenue and The Island in Southwest D.C.[9]

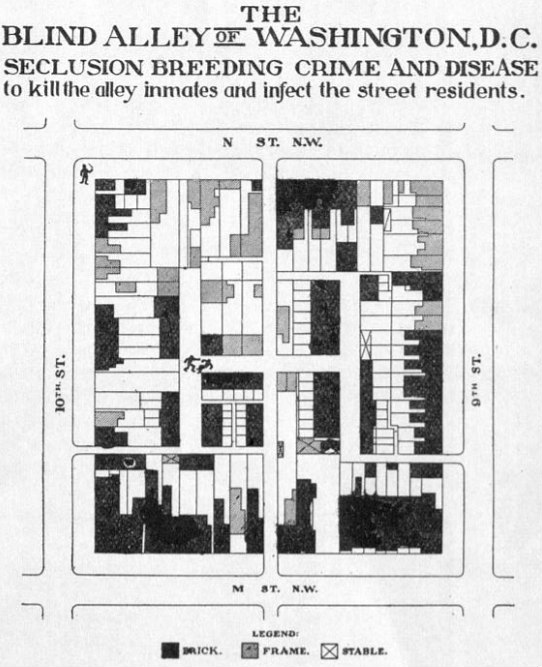

By centering these Black communities of downtown D.C., and the immense police violence undertaken to remove them in order to realize the McMillan Plan, we can arrive at a greater understanding of the intertwined development of imperial Washington and colonial D.C. For those residents who lived, struggled, and survived in the inhabited “blind alleys” of Murder Bay (present-day Federal Triangle) and The Island (present-day Federal Center), the 1902 McMillan Plan was merely one battle in a generations-long “war on alleys” carried out by the Metropolitan Police Department (MPD).[10] Since the Civil War, the MPD had defined itself through the criminalization of the informal economies of mutual aid, sex work, and community defense first developed by fugitive slaves and Irish immigrants in Murder Bay and Southwest D.C.[11] By the time of the McMillan Plan, the MPD had become the behind-the-scenes engine for local urban policy, from housing, education, and labor laws to the reorganization of public charity, the invention of juvenile delinquency, and the professionalization of social work—positioning the policing of Black alley-dwellers as the gravitational center for making D.C. a model of Progressive-Era social reform (Figure 6).[12] Rather than seeing the McMillan Plan as failing to address the social inequalities of the “city beyond the monuments,” taking an alternative view of downtown Washington helps us reframe MPD’s alley policing at the center, both literally and symbolically, of U.S. state-building at the turn of the twentieth century.[13]

Two Views from the National Mall

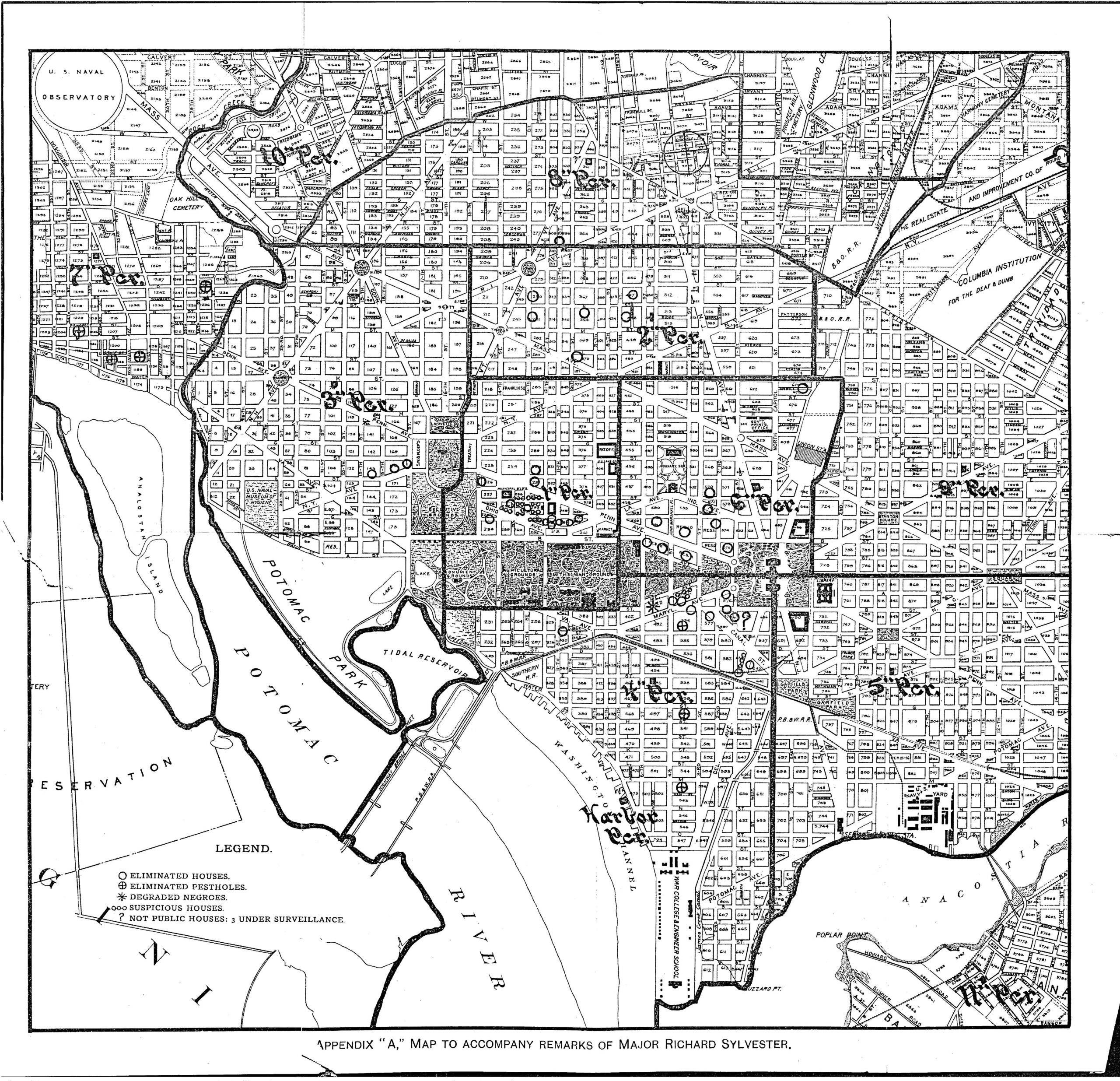

To get a more concrete understanding of the way the MPD’s alley policing made literal space for the McMillan Plan’s symbolic and administrative headquarters of U.S. empire, we can juxtapose the classic artistic depiction of the McMillan Plan with a lesser-known map of MPD alley and brothel raids in downtown D.C. As an essential propaganda tool that accompanied the Senate Park Commission report in museums, magazines, and governmental reports, the drawings and paintings produced for the McMillan Plan imagined the National Mall as a fortified space bordered by yet-unrealized plans for future government offices (Figure 7).[14] In the words of chief architect Daniel Burnham, the McMillan Plan was as much a celebration of “national purpose” to rival the imperial capitals of Europe as it was a local project “to remove and forever keep from view the ugly, the unsightly, and even the commonplace.”[15] However, the McMillan Plan’s fabulous and colorful representations remained, in the words of architectural critic Lewis Mumford, “a remedy on paper” that could only be made real after three-plus decades of politicking, propaganda, and, most importantly, policing.[16] For a more realistic representation, a contemporary map created by MPD Chief Richard Sylvester provides an alternative window into the incredible levels of police violence that helped realize the modern capital of imperial Washington.

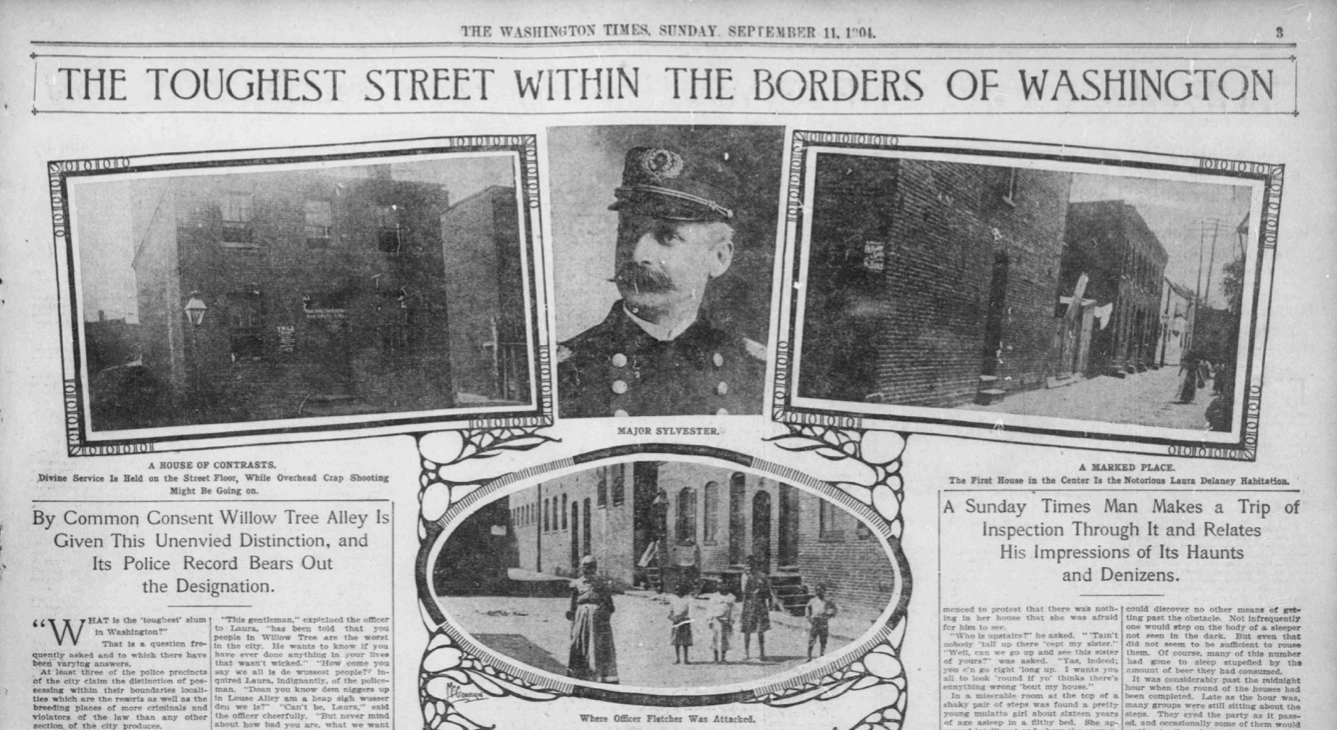

In December 1912, Chief Sylvester stood before Congress and laid claim to much of the Progressive-Era reform victories in D.C.[17] As the longest-serving police chief in MPD history, Sylvester made a name for himself as a “pioneering” police reformer by creating the International Association of Chiefs of Police to combat the global insurgency of anarchism while inaugurating the earliest remnants of a national security state from his municipal office in Washington.[18] So while taking a victory lap at a Senate hearing considering a new law to fight the ubiquitous “houses of ill fame” standing in the way of the McMillan Plan in the alleys of Murder Bay and Southwest, Sylvester could not help but provide a rare “object lesson” of his alley war tenure (Figure 8).[19] Outlining a decade and a half of alley raids concentrated on both sides of the Mall, Sylvester’s map presents a striking juxtaposition to the “remedy on paper” of most McMillan Plan illustrations.

In Sylvester’s map, the McMillan Plan’s grand design for downtown Washington is replaced with hundreds of violent raids, arrests, and condemnations enacted by the MPD to “purify conditions” and eliminate alley life.[20] In the Murder Bay neighborhood, the contemporary headquarters of the Department of Justice, the Agency for International Development, and the National Archives, Sylvester reported the elimination of 70 homes in Graham Alley and Slater Alley. Closer to the Capitol, where local, appellate, and federal courthouses now lie, the MPD succeeded in clearing 35 homes in Marble Alley, Kimball Alley, and Jackson Hall Alley. Of the 158 total homes made unlivable by D.C. police starting in the 1890s, Sylvester’s map reserved special designation for those “Degraded Negroes” of the Southwest neighborhoods of Louse Alley and Willow Tree Alley, where, despite closing 41 homes, almost a hundred alley dwellings of “the lowest class of negroes” remained to haunt the construction of future museum grounds, congressional buildings, and temporary War Department offices (Figure 9).[21] Sylvester’s racist descriptor of Black alley-dwellers as “in their animal state” mirrored the McMillan Plan’s own description of the “degraded” and “degenerated” neighborhoods surrounding the National Mall. The language importantly linked domestic policing in D.C. to the paternalistic, Social Darwinist justifications of U.S. imperialism abroad.[22] By re-mapping the MPD’s “war on alleys” back onto the McMillan Plan’s making of modern Washington, then, we can recast “the city beyond the monuments” as a much more intertwined development between the imperial power from Washington and the racist domestic colonial rule in D.C. Or, as Mumford put it matter-of-factly in his 1924 excoriation of the McMillan Plan: “Can anyone contemplate this scene and still fancy that imperialism was nothing more than a move for foreign markets and territories of exploitation?”[23]

Although downtown Washington today more clearly resembles the drawings of the McMillan Plan, we ought to remember the D.C. alley communities who made cities before—and truly beyond—the monuments. While it remains near impossible to recover the words and ideas of alley-dwellers uncontaminated by the distortions of police archives and social reformer studies, we can still read against the grain of those who only saw disorder in order to appreciate the resistance of those local communities that were policed out of existence to build the imperial capital of the world (Figure 10).[24] For example, where Sylvester and reformers like Charles Weller saw “neglected neighbors” in need of paternalism and punishment, we might find newspaper references to traditions of mutual aid networks of alley residents helping to “bury their dead without assistance,” providing “medical attention for the ill,” and collecting “money to secure bail.”[25] And where Weller and other reformers saw “hidden inner worlds” impervious to police control, we might reveal news coverage of community defense strategies wherein “the arrest of a member of the fraternity is the signal for a general attack by the alley itself.”[26] And when the survival of alley communities in Murder Bay and Southwest D.C. continued to haunt the plans of the most powerful men of Washington for existing, in the words of Labor Commissioner Charles Patrick Neill, “without the law,” we should take seriously the words of an elderly Black alley resident in 1913 when faced with another round of alley reform: “I reckon some folks would a’ gone to law, but I ain’t never been the going-to-law kind.”[27]

Brendan Hornbostel

Brendan Hornbostel (they/them) is a PhD candidate in the History Department at George Washington University. Their dissertation research examines the history of policing in Washington, D.C., as a key site of U.S. state power in relation to DC’s simultaneous status as a racial-domestic colony and the world’s imperial capital.