By Dr. Sara Harwood

April 22, 2020

Working with three first-year students and two graduate students at Georgia State University, I oversaw the development of a self-guided walking tour that uses David Fort Godshalk’s Veiled Visions to describe the horrific events that occurred on Saturday, September 22nd, the first day of the 1906 Atlanta Race Riot. The tour, available for free on Emory University’s mobile-optimized OpenTour website, takes about an hour to complete and extends approximately three quarters of a mile across downtown Atlanta. The race riot raged for three days, as angry mobs stormed from downtown Atlanta to surrounding neighborhoods. Our tour only visits sites connected to the first day of violence, as the distance between those locations allows users to walk easily from site to site. Furthermore, by focusing on just the first day, our team can narrate the events in chronological order. Our tour describes the height of the race riot’s violence while also addressing the failure of law enforcement to protect Atlanta’s marginalized communities.

The tour is a tangible example of public-facing student work, as anyone with internet access can view the mobile-optimized website. Our team hopes that the tour will appeal to local historians and scholars as well as to visitors of the Center for Civil and Human Rights and the Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historic Park, both located in downtown Atlanta. While local museums provide insightful historical information about the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s, our team posits that this tour will provide greater context for understanding race relations in Atlanta in the first half of the twentieth century.

The 1906 Atlanta Race Riot occurred over three days and spanned metropolitan Atlanta. Spurred on by race-baiting in local newspapers, which carried sensationalized headlines claiming that black men on Decatur Street had raped white women, thousands of white men gathered to retaliate in a racially integrated business area in downtown Atlanta on Saturday, September 22, 1906. Violence erupted when a member of the crowd supposedly spotted one of the accused rapists. The mob entered and vandalized black-owned businesses on Decatur and Peachtree Streets, then began disabling and entering streetcars, entering hardware stores to seize weapons, and storming any businesses that were known to employ black men. The mob was finally quieted in part by the arrival of the state militia and by a heavy rain that fell in the early morning hours on the 23rd. Over the next two days, huge white mobs tried to attack black neighborhoods, but armed black citizens prevented further attacks (Godshalk 102). The riot finally ended on Tuesday morning, when the militia deputized white civilians and arrested over two hundred black men. Not only were the white murderers never prosecuted, but licensing officials shut down black businesses permanently and more than fifty black men were charged for possessing firearms (Godshalk 144, 148). Adding to the injustice, traditional historical narratives largely ignore this awful chapter of Atlanta’s history.

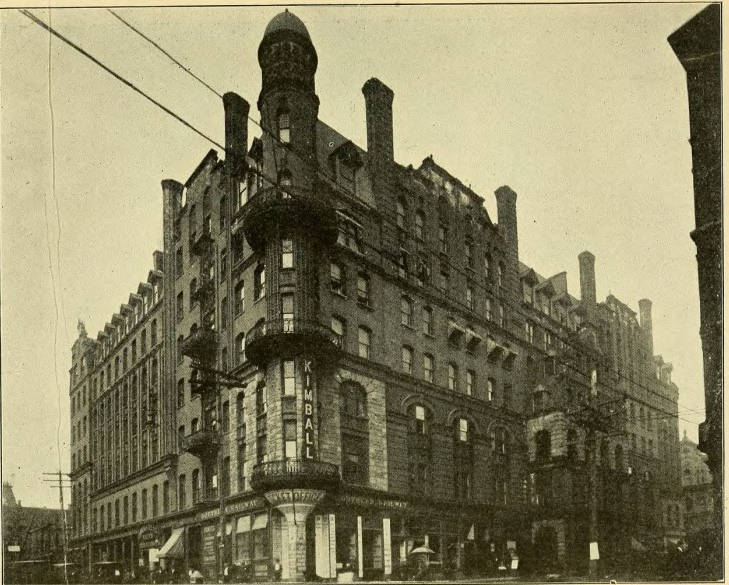

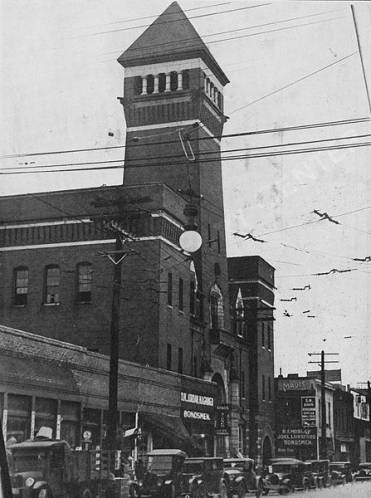

The self-guided walking tour we developed visits eight locations tied to the first day of the rioting. For context, the introduction to our tour briefly narrates the events of all three days of the riot. Our team chose both existing and no-longer-extant buildings for tour stops, selecting sites based on their significance to the narrative of the race riot and the ability to incorporate the site into the tour in chronological order. To create a coherent narrative for our walking tour, we chose sites in a straight line spreading west from the site of the Kimball House Hotel, where the mob first gathered. Stops on our tour include the Five Points intersection, where the mob stopped streetcars in order to attack African-American riders; the Henry Grady Statue, at the foot of which the mob placed the bodies of slain African-American men; and the site of the Bijou Theater, which the mobbed tried to storm before being repulsed by the armed theater manager.

To create this tour, my students and I planned the tour length and distance and plotted what we deemed the most significant sites on a Google Map. Each first-year student was assigned two stops to manage. Using digital archives, students found historic photos of each site and compiled quotations from Veiled Visions describing the role of the location in the race riot. Since publishing the tour in December, we have added two additional stops, bringing the total to eight, and we have begun to compile information about each landmark’s history and significance outside of its connection to the riot. For example, the tour highlights the Kimball House Hotel on Decatur Street in downtown Atlanta as the place where the violence first erupted during the riot, but at that time the hotel was located near one of Atlanta’s few integrated business districts, renowned for its black-owned businesses. This reputation, in fact, made Decatur Street one of the rioting mob’s primary targets. Similarly, as many of the historic buildings affiliated with the race riot no longer stand, we hope that this tour will highlight not only what happened in downtown Atlanta in September 1906, but how dramatically the built landscape has changed in the past century. We plan to add the seventh and eighth stops and the supplemental historical information to the website by the end of the spring semester.

Ours is the first self-guided online walking tour, but we were not the first scholars to create a 1906 Race Riot walking tour. Beginning around the centennial anniversary, the late Clifford Kuhn, professor of History at Georgia State University, led a bi-weekly walking tour for close to a decade. Recently, Civil Bikes, a local startup devoted to publicizing revisionist place-based history, offered a commemorative guided walking tour. These guided tours focused on describing the political and social context of the riot and on narrating the gruesome events of September 22. They rightfully cast blame for the riot on careless newspaper reporting and the ignorance and maliciousness of the mob.

Our tour’s narrative differs slightly by beginning and ending not at the places where the rioting began and ended but instead at the nearby locations affiliated with law enforcement authorities. Further revealing the extent of racism among white society in 1906, our tour demonstrates that despite their proximity to the violence, these law enforcement authorities did not intervene to protect the victims of the rioting. Instead of beginning the tour at the Kimball House Hotel, where the rioting actually erupted, we start our tour at the site of the Atlanta Police Department, now a modern classroom building in the center of Georgia State University’s downtown campus. We chose this starting point in order to illustrate the close proximity of the Atlanta police to the center of violence. The Atlanta police hesitated to become involved and claimed later that they were unable to act efficiently because their telephone wires had been cut (Godshalk 96).

Our tour then continues one-third of a mile west, to the location of the Kimball House Hotel and proceeds west, following the path of the 1906 mob. The tour ends at the location of the governor’s mansion, a third of a mile north of Five Points, the epicenter of the rioting. By the time the governor chose to summon the state militia, shortly after midnight on September 23rd, the rioters had murdered dozens of African-Americans and injured scores more (Godshalk 97). Despite having been at home all evening in such close proximity to the violence, the governor claimed to have slept through the riot (Godshalk 97). By beginning and ending the tour at the sites of the authorities who had the power to thwart the violence, but seemingly chose not to, we intend to demonstrate how law enforcement officials failed the victims of the riot. We offer minimal commentary beyond presenting this observation, but we hope that this tour encourages people to reflect critically upon the willingness of local authorities in 1906 to shirk their responsibility to protect in favor of abetting the violence.

In addition to sharing important information with the public, this project helps students prepare for their post-college careers. Our team is part of the Mapping Atlanta Project Lab, a component of the Experiential Project-Based and Interdisciplinary Curriculum Program (EPIC) launched last fall at Georgia State University. I became involved in this project through the Atlanta Studies Teaching and Learning Community (TaLC), which I joined upon its 2017 launch. The TaLC is a volunteer organization of faculty and graduate students from Georgia State University and Perimeter College who meet monthly to develop pedagogical resources on public history and urban studies. Members of the Atlanta Studies TaLC contribute publications to the Atlanta Studies network and teaching resources to Teaching Atlanta. Although I am affiliated with the Mapping Atlanta Project Lab, the TaLC, and the Atlanta Studies network, these organizations are not officially connected. Through the TaLC, I met Brennan Collins, who supervises EPIC and invited me to participate in the Project Lab.

EPIC’s Project Labs program, modeled on the Vertically Integrated Projects concept developed by the Georgia Institute of Technology, aims to develop career readiness skills, particularly for students majoring in Arts and Humanities. These labs bring together faculty and students from multiple disciplines including the sciences, social studies, and the humanities. Because of their collaborative nature, the labs provide students with excellent opportunities to work directly with faculty as well as with students from other majors. Students build skills and learn technologies that are not traditionally taught in the classroom. For example, participants meet weekly with the program’s supervisor, Brennan Collins, to learn digital mapping technologies such as Google Maps and ArcGIS.

The students on our team also develop hands-on archival research skills by using digital archives to locate historical images that we include at each stop on our walking tour. In turn, students learn first-hand about copyright and about approaching research institutions in order to request the rights to use archival materials. While traditional college essays require students to learn about citations, this project offers a real-world example of the importance of proper attribution and the potential consequences of not respecting copyrights. This project similarly strengthens students’ communication skills, as it requires our team to think about how to summarize our research efficiently for a mobile website and to consider the appropriate terms and context to include in order to address a broad public audience.

Because this tour is public-facing, students can include a link to it in their portfolios and refer to this project when applying for jobs. This project illustrates that these students have developed research skills and technological knowledge while optimizing their communication skills and working on a team. As the faculty supervisor for the project, I am overjoyed by how successfully we have met our goals. The walking tour has not only granted the students on our team the opportunity to learn about an important historic event, but they have done so while developing demonstrable practical skills that they will be able to use after they graduate.

Middle Cover Image

Five Points, Kenan Research Center at the Atlanta History Center, Francis E. Price

Dr. Sara Harwood

Sara Harwood is a Visiting Lecturer at Georgia State University, where she graduated with her Ph.D. in American Literary Studies in 2018. Her research interests include early American theology, place and public memory, and composition pedagogy. The Veiled Visions Mapping team members are Dionne Clark, a Ph.D. student; Pat Barrett, an M.A. student; and first-year students Alex Barnett, Aaliyah Brunson, and Chelsea Price.