By Andrew Wender Cohen

September 11, 2024

Over the next several weeks, we are going to be publishing a forum on the history and legacy of Anthony Comstock. This forum is forthcoming in the Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era and is formally titled The History and Legacy of Anthony Comstock and the Comstock Laws. Given our current debates on abortion following the Dobbs decision and the Heritage Foundation’s Project 2025, which proposes to revive the Comstock Act, we hope this forum will provide useful historical context about the Act’s influence on American life. This is the second of seven installments. All posts will be available here as they are published.

It is best to think of Anthony Comstock’s campaign against vice as a response to Reconstruction that afflicted the nation long after that period was over. Comstock’s rise in the 1870s was not organic; it was backed by wealthy patrons engaged in intense political fighting over issues such as racial equality, taxation, and democracy. And although Comstock began by arresting vendors of so-called obscene goods, he soon expanded his portfolio, pursuing folks of every race and gender engaged in erotic, profane, or blasphemous correspondence. Interfering in personal conversations proved controversial, resulting in attempts by courts and postmasters to restrain Comstock’s authority, but he nevertheless prosecuted countless letter writers. The law that bore his name resulted in federal involvement in private correspondence well into the twentieth century.

Far from a lone crusader, Anthony Comstock was an active participant in the Reconstruction-era battle between Radicals and evangelical Republicans to determine the proper uses of federal power. His sponsors were Christian moguls, who favored what historian Gaines Foster has called “moral reconstruction,” that is, government policies promoting individual sobriety, continence, and religiosity. Consider William Earl Dodge of Phelps, Dodge & Co., the nation’s pre-eminent metal merchants. Dodge generously supported organizations promoting Protestant values at home and abroad. He was the president of the National Temperance Society, as well as a founder of the Syrian Protestant College and the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) of New York City. Yet Dodge never truly embraced any cause that interfered with profits. Publicly anti-slavery, he nevertheless traded English copper for Southern cotton. During the war, he lobbied for compromise with enslavers, arguing that bloodshed was bad business. After Appomattox, he served as a one-term Republican U.S. Congressman, demanding reconciliation with defeated Confederates to protect his Georgia timber and railroad investments.[1]

Dodge and his allies reviled the Radical Republicans who had dominated Congress for the past five years. At this moment, the leading Radical in Congress was General Benjamin Butler of Massachusetts. Butler sought to construct a majority coalition through attacks on the wealthy, defenses of Black southerners, support for women’s rights, and the rejection of overtly Christian policies. A key component of his agenda was higher taxes on foreign goods to pay the federal government’s $2.7 billion debt. A master of the art of patronage, Butler secured the appointment of his clients at the Port of New York. Between 1869 and 1872, these representatives aggressively pursued importers for undervaluing their goods to avoid taxation. The old money merchants thus viewed Butler as a corrupt demagogue, intent on inverting their world.[2]

Comstock was an obscure Brooklyn temperance advocate until 1872, when the YMCA and its backers – Dodge, financier Morris Jesup, and soap manufacturer Samuel Colgate – elevated him.[3] Early in the year, he established himself in Manhattan. In March, newspapers announced he had obtained a warrant for police to search several Ann and Nassau Street bookstores for “bawdy and obscene literature.” In the ensuing eight months, representing the YMCA, Comstock claimed to have seized 181,000 “impure” images and five tons of books, arrested thirty-nine, and secured twelve convictions or guilty pleas. In a particularly macabre moment, he bragged that five alleged perpetrators had died during his campaign.[4]

Comstock’s crusade caught fire partly because this was a moment of genuine panic over American sexual mores. Inexpensive erotica was now available due to advances in printing technology.[5] Critics labeled the U.S. Treasury a “house for orgies and bacchanals” when newly hired female employees fraternized with their male co-workers.[6] Journalists gossiped about New York City’s first drag balls in 1861, lobbyists cavorting with female sex workers in male attire in 1868, and U.S. diplomats being recalled for conspiring “to commit buggery” in 1870.[7] Advocates of free love and liberalized divorce had gained significant popular support since 1850. Women’s rights activists’ newly aggressive approach to politics frightened many observers.[8] Most disturbing to elite evangelicals were scandals involving their relatives, such as the January 6, 1872, shooting of financier Jim Fisk by aristocratic playboy Ned Stokes over the love of a notorious showgirl.[9]

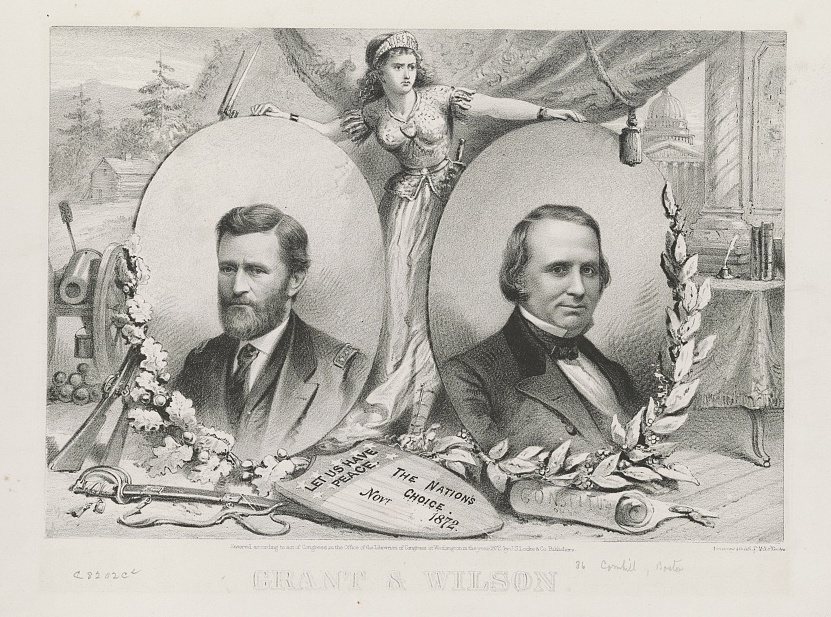

Yet more than anything, it was the 1872 presidential election that elevated Comstock to national stature. On one side was the Republican incumbent Ulysses S. Grant, the victorious general in the Civil War. Not a Radical, he had the support of those favoring a military presence in the South and an aggressive customhouse. On the other side was the mercurial Horace Greeley, the editor of the New York Tribune, and once an idealistic anti-slavery Republican. Having soured on the armed occupation of the former Confederacy and becoming convinced that the Grant administration was corrupt, Greeley obtained the nomination of the Liberal Republicans, a party that had achieved some success in the midterm Congressional elections. It was a shock to the entire political world when the Democratic Party decided to unify the opposition to Grant by also nominating Greeley – a man who had spent his career excoriating Democrats – for the presidency.[10]

With voting just weeks away, open combat erupted between Radicals and evangelicals. Since 1870, sisters Victoria Woodhull and her sibling Tennie Claflin had published a newspaper promoting women’s suffrage, free love, and other shocking notions. On October 29, 1872, allegedly at the instigation of General Butler, they published an exposé of the Reverend Henry Ward Beecher, minister at Brooklyn’s elite Plymouth Church. Beecher, they charged, had seduced Elizabeth Tilton, the wife of Theodore Tilton, Greeley’s campaign manager. Though the revelations are usually remembered as an attack on sexual hypocrisy, their timing and targets suggest their goals were electoral. They simultaneously wounded the Democratic candidate and delegitimized Beecher, an ally of the evangelical businessmen whose support for Grant had been lukewarm. In response, on the second of November, Anthony Comstock convinced federal marshals to seize all copies of the newspaper and jail the sisters on charges of obscenity.[11]

General Butler retaliated against Dodge in his own fashion. In December 1872, his representatives at the Customhouse seized a $1,750,000 shipment belonging to Phelps, Dodge, & Co. on account of a $7,000 undervaluation in their customs declaration. To re-acquire their goods, the company paid a settlement of $271,000. New York City’s outraged merchant community rallied around Dodge, prompting allegations of corruption at the Port. Butler responded by publishing his own pamphlet calling Dodge a tax cheat and phony reformer.[12]

This political battle between Radicals and evangelical businessmen was the context for Comstock’s rapid rise in the year 1873. In the aftermath of his arrest of Woodhull, he became the secretary of the new Society for the Suppression of Vice (SSV), an organization whose founders included his longtime backers, William Earl Dodge, Morris Jesup, and Samuel Colgate, as well as America’s foremost young investment banker, J. P. Morgan, and Henry Ward Beecher’s son, William. From this position, Comstock continued to raid book dealers and doctor’s offices under state obscenity statutes. But Congress’s enactment of the so-called Comstock Law of 1873 made him a special postal agent, with the ability to pursue ordinary individuals transmitting words dubbed obscene through the U.S. Mail.[13]

Comstock arose at a crucial moment, when the nation was deciding how to use the power the federal government had acquired in the Civil War. Butler and many others wanted to protect the civil rights, personal safety, and material well-being of formerly enslaved people. They wanted to collect taxes owed on foreign goods. Comstock and his backers proposed deploying the central government to punish sexually immoral individuals by surveilling the correspondence of the American people. Nearly from the moment of the law’s passage, Comstock desired the authority to open and read mail. In June 1873, Comstock “demanded possession of all letters directed to newspapers by initials and single names” claiming “the right to open and inspect” them “by virtue of his position as special agent.”[14]

Federal officials refused him this authority. On June 7, the postmaster for New York City, Thomas L. James, replied, “I am certainly unwilling to run the risk of doing serious injustice to innocent individuals, and unwarrantably interfering with legitimate private correspondence, however laudable in itself the object of such an action might be.” His superior, Postmaster General John Creswell, a Radical Republican, endorsed James’s decision, and newspapers cheered this “snub” accusing Comstock of “cheek and ignorance.”[15]

Perhaps chastened, Comstock focused on commercial mail until 1876.[16] Indeed, when pressed by Congress on the matter in February of that year, he denied asking for “the privilege of opening letters.” But just a few months later, Comstock initiated the prosecution of Elsie Hallenbeck of Catskill, New York. For three years, Hallenbeck had sent anonymous letters harassing her lover’s estranged wife, Mary Wetmore, in the hopes of convincing her to leave town. Though sympathetic to Mrs. Wetmore, local newspapers mocked Comstock for insisting on “defending the purity of the United States mails.” The judge quashed the indictment, but Comstock’s exposure prompted Hallenbeck’s lover to leave Catskill for Kansas in 1882, without her or his wife.[17]

Likely noticing this new aggressiveness, in 1877, critics reminded Comstock he had no authority to search the sealed letters. One observer, a pseudonymous writer in the New York Sun called “Ajax,” insisted that Comstock was interfering with private correspondence, no matter what he claimed. A week later, the New York Postmaster James took the extraordinary step of issuing a second rebuke to Comstock, instructing him to cease interfering with the mails. Noting that Comstock had “no more authority to detail letters than any private citizen,” he henceforth had to “proceed through and not independent of the Postmaster.”[18]

Nor was the scolding limited to the Post Office. When the U.S. Supreme Court considered the constitutionality of the Comstock Law in Ex parte Jackson (1878), Justice Stephen Field limited the act’s scope to commercial mail rather than private communications. “All regulations” Field stated, “must be in subordination to the great principle embodied in the Fourth Amendment of the Constitution,” namely “the right of the people to be secure … against unreasonable searches and seizures.” The justice insisted that “no law of Congress can place in the hands of officials connected with the postal service any authority to invade the secrecy of letters and such sealed packages in the mail.” Comstock might have expected more from Justice Field, a minister’s son and opponent of Radical Reconstruction, but the jurist saw private morality and private property as equally sacrosanct. Though the SSV rejoiced that the court had affirmed the act, its repudiation of Comstock’s broader claims to authority must have stung.[19]

Yet remarkably, Comstock’s policing of personal correspondence only increased. In November 1879, he pursued Fanny Hoffman, a Manhattan housewife, for mailing letters deemed obscene to her neighbors. Then in early 1880, he arrested Edward F. Williams, a Brooklyn bank president and the brother of the former president of the Republican General Committee, for sending indecent anonymous letters to several other prominent residents of the borough. In both cases, the courts rebuked Comstock. He was unable to prove his charges against Hoffman, who convinced the grand jury to indict the vice crusader for assault. In the Williams case, the federal magistrate concluded that an “anonymous … strictly private letter, sealed, and with nothing objectionable on the envelope” was not “within the scope of the law.”[20]

These cases provoked outrage against Comstock. After conclusion of the Williams trial, the Brooklyn Eagle demanded either the repeal of the law or that someone make Comstock “understand that the reputation and liberties of decent citizens cannot, with safety or profit, be attacked.” Williams’s attorney all but accused Comstock of blackmail, observing, “Oh, it is so natural and so in his line to make charges against officials who do not bend the pregnant hinges of the knee to him.” Other responses were still less tempered. A small-town Minnesota newspaper called Comstock a “devil,” who was “enriching himself out of his infamous business,” predicting he would either “be killed by some of his victims or will end his career in prison.”[21]

Comstock stubbornly continued. Seeing erotic or merely profane mail as no different from letters sent to intimidate, Comstock turned private disputes into federal cases through the remainder of the century. He arrested a divorced wife for writing nasty letters to her ex-husband, who had “sold all her property and left her destitute.” When Minna Irving, a young Tarrytown poetess, gave Comstock torrid letters written by her former lovers in 1888 and then again in 1892, he pushed for them to be charged with obscenity. Then Comstock arrested an unfaithful husband, Charles W. Pease, when his wife found love notes he had written to his employee. He pursued, but ultimately declined to arrest, Frank DeNyse, a transgender man, for writing flirtatious letters to women.[22]

Meanwhile, in areas outside Comstock’s reach, such cases proliferated under the act bearing his name, affecting people of every type. As Magdelene Zier will discuss separately in a later post in this series, a “network of bureaucrats,” religious organizations, and local crusaders arose in other places. A Toledo judge sent Civil War hero Shepley Holmes to the workhouse in 1887 for mailing a strongly worded letter warning his nephew about his aunt. In 1889, a Baltimore grand jury charged Laura Landon, a Black woman, for sending a letter to another Black woman, Martha Briscoe, calling her a vile name. That same year, another Black resident of Baltimore, Charles H. Norton, spent thirty days in jail for posting a letter telling a mother about her child’s sexual behavior. An 1894 federal court acquitted Jim Lee, the “King of Buffalo’s Chinatown” for allegedly mailing an indecent letter in Chinese calligraphy.[23]

And so, during the very period when the United States federal government renounced responsibility for protecting Black civil rights, Anthony Comstock and his allies pushed it to focus on guarding Americans from insulting or explicit mail. That this was a choice was evident in 1873, the year Comstock rose to prominence. His crusade was a response to Reconstruction-era politics as much as changing sexual values. It sought to prosecute individuals for immorality rather than remedy society’s larger systemic issues, such as poverty, white supremacy, and patriarchy. And Comstock’s long career continued to pull the nation’s gaze away from more salient problems well into the twentieth century.[24]