By Dr. Nancy C. Unger and Dr. Christopher McKnight Nichols

March 29, 2022

This review contains small spoilers.

Our co-edited collection, A Companion to the Gilded Age and Progressive Era Wiley (Wiley Blackwell, 2017), will be released in an updated, paperback edition this spring. As scholars who have long been immersed in this pivotal period, we were excited to learn of the lavishly produced HBO series The Gilded Age. With the exception of the fabulously successful feature film Titanic in 1997, ours is a historical period that is often overlooked in popular culture. So we were delighted when The Gilded Age generated advance reviews in mainstream publications including the New York Times and Washington Post. We hoped it would bring attention to the period we find so important in our history, especially for the light it can shed on present day problems and issues—both how they were created and how they might be remedied.

Our reaction to the first season is mixed. Certainly it is a gorgeous series: the lavish sets and beautiful costumes are dazzling, reminiscent of those in the British series Downton Abbey. This is no coincidence, as both series were created by Julian Fellowes, who, in his ability to portray the incredibly wealthy and privileged class, is to be commended for his attention to historical detail.

Like Downton, The Gilded Age focuses primarily on interpersonal relationships. Most of the conflict centers on who will prevail, the Old Money families of New York who have been controlling its social scene for generations, or the New Money families who make up for their lack of genteel history with grand fortunes generated in the new industrial age.

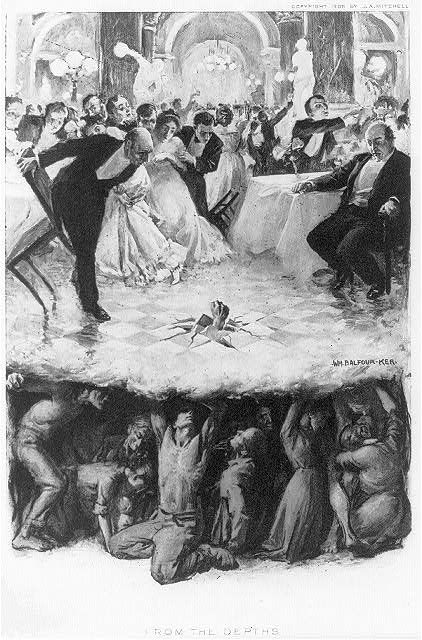

While there is much to criticize and much to celebrate in this series, our particular frustration comes down to its title. This period was termed “gilded” (gold plated) rather than solid gold. “The important word is gilded,” Fellowes expounded in an interview with Entertainment Weekly. “[T]hat tells us it was all about the surface. It was all about the look of things, making the right appearance, creating the right image.” In Fellowes’ rendering, the “gilt” of the era was glittering indeed. The series’ characters are modeled on the real-life Americans who made vast fortunes providing steel, oil, meat, beer, timber, and all the other raw materials, manufactured goods, and services vital to a burgeoning nation. But beneath this dazzling exterior chockablock with such modern marvels as street cars, telephones, electric lights, and inexpensive manufactured goods, darkness lurked. The economy was unregulated and frequently rocked by recessions and depressions.

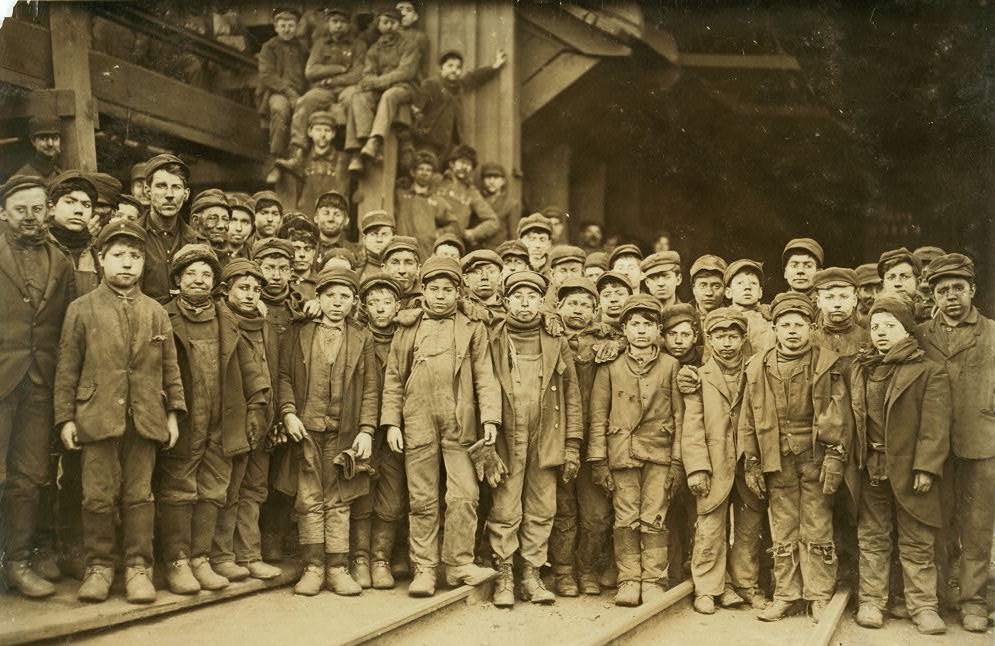

What was the source of all this wealth? A short answer is foreign capital and foreign peoples. Immigrants poured in, providing much of the labor force of industrialized America, while flaring anti-immigrant sentiment and rising xenophobia was embodied by everyday acts of violence and discrimination, and laws such as the Chinese Exclusion Act (1882). Dreams of the United States as a land of glorious opportunity, however, seemed to be realized exclusively by the already wealthy who pulled the ladder up after themselves rather than allow others to ascend. What remained were menial, often dangerous jobs so low paying that frequently the labor of the entire family was necessary for survival. After long hours in dangerous conditions, workers returned to urban ghettos rife with poverty, crime, and disease.

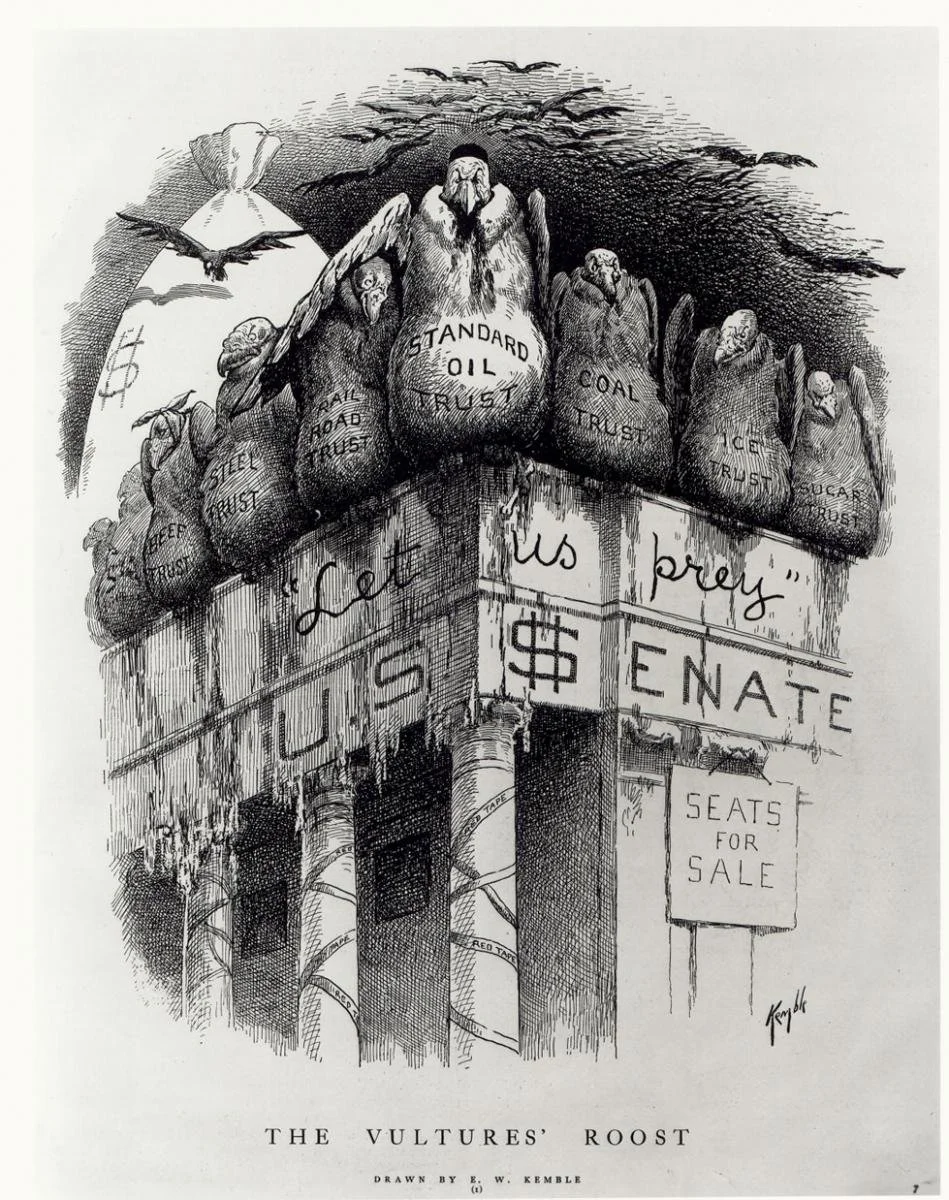

Precious, nonrenewable resources were decimated with no thought to their conservation, let alone preservation. And the government appeared, at best, helpless to curb the harmful excesses, at worst a willing collaborator in the profitable carnage.

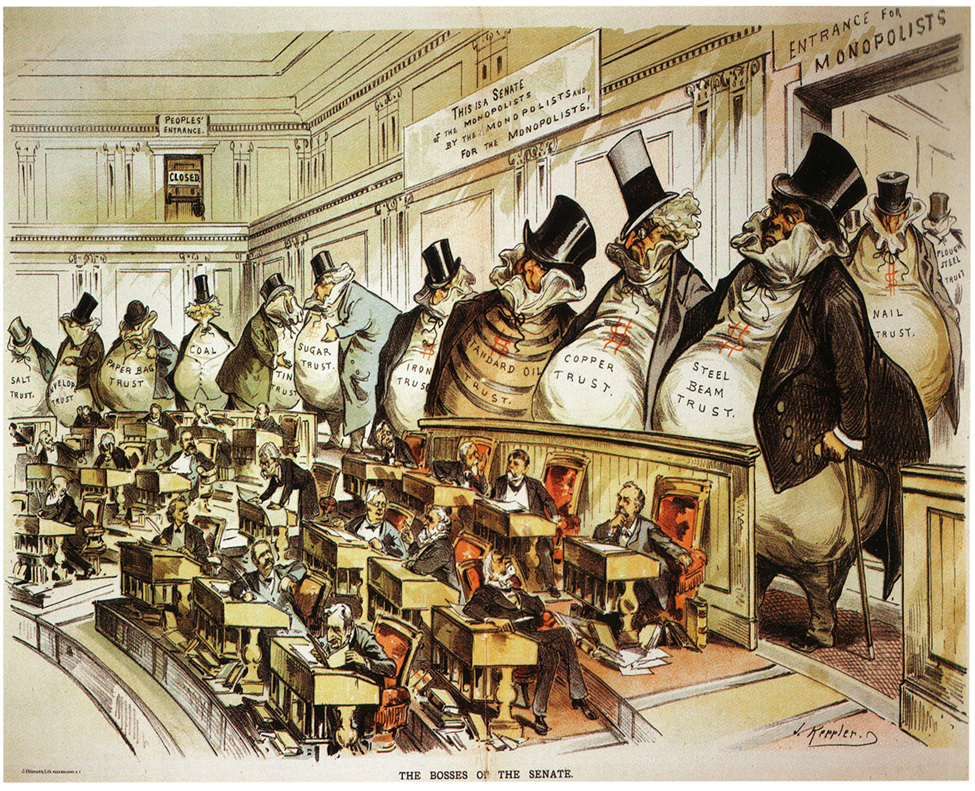

Politicians like New York’s Boss Plunkitt spoke openly and approvingly of “honest graft.” A seat in Congress (known as the Millionaire’s Club) could be purchased merely to increase a wealthy man’s status. More often, however, it was used to protect and promote his business. U.S. Senators were not elected directly by the people but were selected by state legislators, frequently through backroom deals.

So, too, investments from within the United States and far beyond, from England and France in particular, poured in. Foreign investment dovetailed with domestic lending and investing practices that were often taken at great risk to speculate on railroads and emerging industries with hopes for enormous profits; such practices added additional unpredictability to the era’s economic boom and bust cycles, underscoring both the opportunities and dangers of a minimally regulated and rapidly expanding American industrial and financial system.

In episode three of The Gilded Age, there is a realistic business battle. Aldermen, practicing “honest graft,” leak information about new laws to manipulate stock purchases based on their insider information. To enrich themselves and hurt rivals, they make use of what was heralded as a new investment mechanism in the late nineteenth century: buying on margin and shorting stock. Such efforts, however, were unpredictable because they tended to leave the investors dramatically over-leveraged and thus exposed to ruin should their assumptions be flawed or if stock prices rose as others invested their capital to thwart such efforts.

In The Gilded Age, the aldermen’s machinations fail to yield the fruits they expected, leading to disaster in terms of both finance and reputation. To tell this story, the show focuses on the new-money Russell family, working to break into social circles and challenge both business and social norms. The storyline does a solid job of revealing the ruthless path by which minimal regulations and weaker competition, or less savvy antagonists, could be thwarted on the road to Gilded Age money and power. But as the show implicitly suggests this came at the expense of lives and livelihoods far beyond the moneyed elite. Their great wealth was built on the backs of poorly paid workers with little say over working conditions, wages, hours, or much else.

Bowing to present day sensibilities, the show refrains from focusing exclusively on the white men who wielded the era’s economic and political power. Homosexuality is depicted and women, particularly wealthy women, figure prominently in the various plot lines. Perhaps the most charismatic character in the series is played by Christine Baranksi, who stars as Agnes van Rhijn, a wealthy widow with family roots in the Colonial Era elite. Her character seeks to maintain control of New York’s social power and prestige, battling against a second most significant female star, the new money social climber Bertha Russell (Carrie Coon).

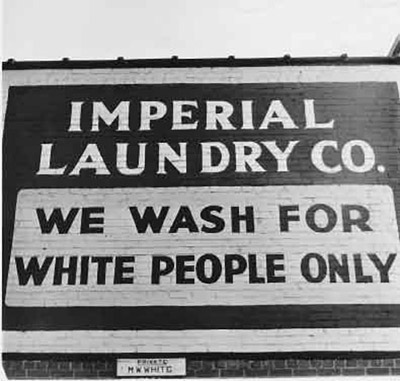

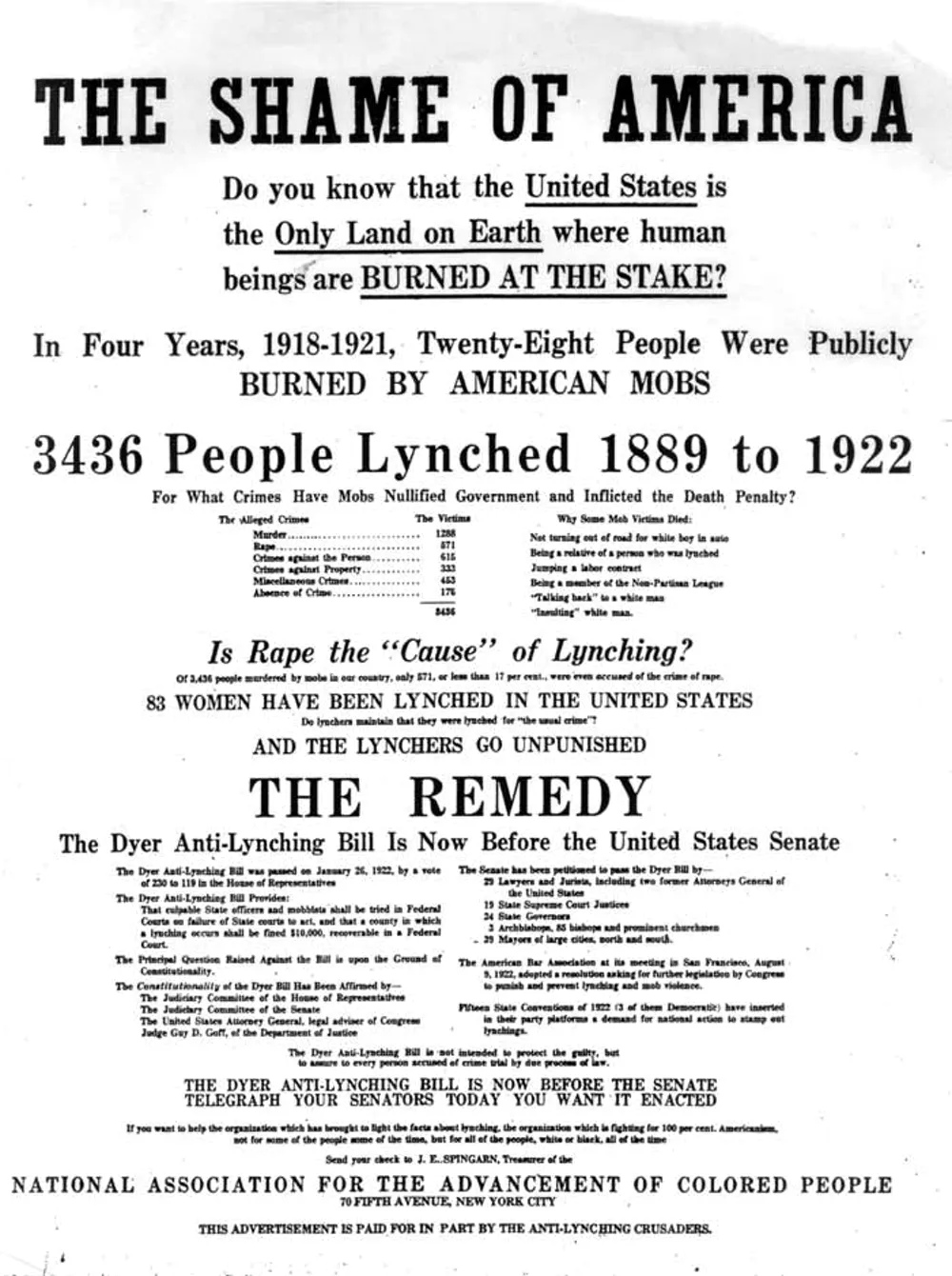

In The Gilded Age, racism is depicted as a rather genteel practice, characterized by rudeness and socio-economic limitations rather than by the extreme segregation and frequent poverty, terrorism, and violence of the actual period. Certainly racism was less intense, or at least less visible, in the wealthy New York City community featured in The Gilded Age than in the deep South. In reality, however, the Gilded Age has been termed the nadir of post Civil War race relations nationwide. It was marked by the institutionalization and legalization of racism, dramatically revealed by the landmark Plessy v. Ferguson decision (1896) in which the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of racial segregation under the “separate but equal” doctrine.

In the ensuing decades, despite valiant efforts by civil rights activists, Congress failed to pass anti-lynching legislation nearly 200 times, and the filibuster was increasingly used in the U.S. Senate as a means of blocking civil rights laws.

Fellowes has every right, of course, to focus on whatever aspect of this period he wishes. Our worry is that by entitling his series “The Gilded Age,” he’s misrepresenting the period to a very large audience. While it may accurately capture the cutthroat business tactics of the era, the ugly base beneath the gilt exterior remains unexplored, hinted at by the portrayal of limited educational and career options for women and by the inclusion of characters from the African-American middle class (a focus that some have praised) who are repeatedly subjected to thinly-veiled racism and social exclusion. The only other non-elites featured are members of the servant class with no suggestion that they enjoy relative comfort and security compared to the vast working class. In short, this series generally presents the early 1880s to be a wonderful period of wealth and glamor. It’s an era to be celebrated for its lavish excesses and examined primarily for the internecine squabbling among its top 1 percent.

It seems a bit unfair to be so critical of a misleading title. Certainly some of the appeal of Edith Wharton’s novel The Age of Innocence (made into a feature film in 1993), which also centers exclusively on questions of who belongs among the New York elites, is that title’s intentional irony. But for a popular series to focus almost exclusively on the gilt of the era, and hint only briefly at the dark forces that served as its foundation is a disappointing misrepresentation of this complex and important period.

Anyone hoping that The Gilded Age grapples with some of the more important issues and controversies of the actual Gilded Age is in for disappointment.