By Chelsea Chamberlain

June 23, 2020

This is the third post in our series exploring the lived experience of the 1918 influenza pandemic. Read the other posts in the series here.

Between August 14 and August 19, 1908, the Pennsylvania Training School for Feeble-minded Children at Elwyn admitted seven new “inmates,” part of the yearly influx of new arrivals before the school year began. They ranged in age from seven to twenty and received diagnoses at the highest (“high grade imbecile”) and lowest (“excitable idiot”) ends of the classification scale used by Elwyn’s superintendent, Dr. Martin Barr. During their time at Elwyn some of them learned woodworking, floor scrubbing, laundry, or chicken keeping. Their unpaid labor was crucial to the maintenance of Elwyn’s budget and staffing levels, both of which were stretched impossibly thin. Other “inmates” were deemed “helpless.” These were placed in locked custodial wards, where they relied on nurses, attendants, and fellow residents to meet their daily needs. By November 1918, only one of the seven newcomers was still alive.[1]

In his 1919 annual report, Superintendent Barr announced that 138 of the 1,055 people under his care died the previous year. The influenza epidemic had so decimated their population, he wrote, that boys from a nearby boarding school had been brought in as grave diggers after their own were exhausted.[2]

The institution was caught entirely unprepared by the epidemic. Like many of the nation’s institutions for the so-called “feebleminded,” Elwyn had been chronically overcrowded and understaffed almost from the moment of its founding in 1852. At the turn of the century, Pennsylvania had established public institutions that expanded the commonwealth’s institutional capacity beyond semi-private Elwyn, but Barr nevertheless oversaw overcrowded wards and a waitlist hundreds long. In 1917, U.S. entry into World War I further exacerbated these conditions, when many staff and a cadre of male residents who performed valuable unpaid labor left to join the war effort. As the disease swept through nearby Philadelphia in the weeks after the city’s infamous super-spreader parade, it also overwhelmed Elwyn’s grounds. The “avalanche of unexpected sickness,” Barr reported, infected more than 80 percent of the institution’s population.[3]

The influenza epidemic of 1918 has become a global touchstone for our present moment, but when I first began dissertation research several years ago in the newly opened archive at Elwyn, it was not even on my radar. My dissertation is not about disease but instead about how vernacular ideas about dependence and citizenship shaped families’ interactions with psycho-medical diagnosis, institutionalization, and education during the Progressive Era.

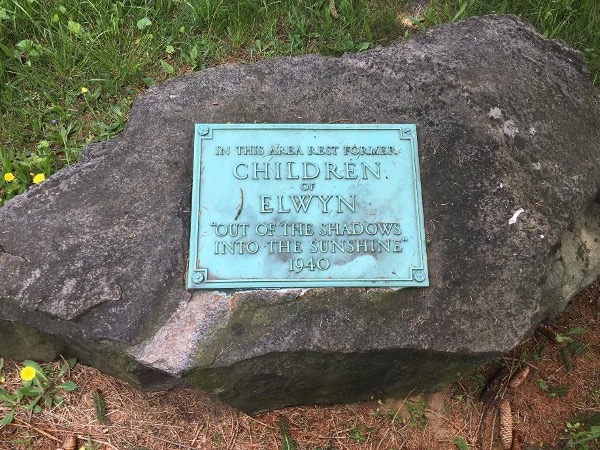

My work emphasizes the surprising power with which institutionalized people, their families, and their teachers upset institutional regimes and resisted custodialism even at the height of eugenic fervor in the first two decades of the twentieth century. Yet Elwyn’s leather-bound Medical Record books make clear the stark limitations of that power in the face of influenza’s deadly impact. The records provide a glimpse into the lives of Elwyn’s residents: a name and registration number are followed by dates of birth, admission, and removal. A short description of the resident’s appearance, behaviors, perceived “peculiarities,” and their reported family history gives way to a chronological record of events including “spasms,” illnesses, accidents, and surgeries such as tonsil removals or sterilization procedures.[4] I quickly learned that when an entry opened with a removal date in October 1918, it would conclude with the note “Death from Influenza.” Many of those who died, particularly those whose parents were too poor to transport their bodies back home, lie buried in Elwyn’s cemetery alongside hundreds of others.

In 1918, the segregation and devaluation of people deemed feebleminded was widespread and explicit. The psycho-medical experts who oversaw the nation’s institutions spent their annual meeting not mourning those who died, but rather celebrating that wartime intelligence testing might bolster their profession’s status. Their discussion of the epidemic was shockingly brief and revealed that at least one superintendent had treated it as a research opportunity by administering vaccines to only half of his institution’s residents.[5] Clearly unconcerned about whether high mortality rates might harm their reputations as competent medical providers and administrators, the experts did not pause to consider how influenza had laid bare the deadliness of congregate care, of housing people with complex needs in facilities too large to meet those needs. Perhaps they simply accepted the epidemic as nature’s unanticipated contribution to their ultimate pursuit of the elimination of the unfit.

Over the last sixty years, deinstitutionalization has shuttered these mega-institutions, and the harsh rhetoric of eugenics has largely faded. Yet the coronavirus pandemic has laid bare American society’s continued willingness to devalue disabled people and dismiss their deaths. Indeed, many of those closed institutions reopened as prisons in which disabled people are dramatically overrepresented.[6] Although congregate care facilities for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities are now smaller and more decentralized than in the early twentieth century, they remain underfunded, improperly staffed, and deadly. Alongside prisons and nursing homes, these facilities have proven especially vulnerable to the coronavirus outbreak. State-issued guidance for rationing treatment and stories of experimental drug treatments being performed on nursing home residents echo the chilling priorities of experts a century ago. Despite increased knowledge about how disease works, these facilities have once again experienced a viral epidemic as an “avalanche of unexpected sickness.” I hope that, unlike in 1918, we will grieve the loss our society has inflicted through these people’s unnecessary deaths and use that grief to finally recognize and dismantle the deadliness of congregate care.

Chelsea Chamberlain

Chelsea D. Chamberlain is a PhD Candidate in History at the University of Pennsylvania and a 2020 NAEd/Spencer Dissertation Fellow. Her research explores the history of education, politics, and medicine in the United States in the nineteenth and twentieth century. She received her MA in History from the University of Montana and a BA in History from Whitworth University.