September 4, 2024

Over the next several weeks, we are going to be publishing a forum on the history and legacy of Anthony Comstock. This forum is forthcoming in the Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era and is formally titled The History and Legacy of Anthony Comstock and the Comstock Laws. Given our current debates on abortion following the Dobbs decision and the Heritage Foundation’s Project 2025, which proposes to revive the Comstock Act, we hope this forum will provide useful historical context about the Act’s influence on American life. This is the first of seven installments. All posts will be available here as they are published.

Forum Introduction

By Magdalene Zier, Lauren MacIvor Thompson, Cathleen Cahill, and Kimberly A. Hamlin

Anthony Comstock arrived in Washington, D.C., in January 1873 with a collection of pornography and big plans for what to do with it. Bearing a veritable grab bag of explicit images, books, pamphlets, contraceptives, and sex toys that he had ordered expressly for the purposes of shock, he set up displays, first in the private homes of legislators and then in the office of the vice president inside the congressional building.[1] As congressmen trooped by to gawk, Comstock spoke to them about the “nefarious business” of obscenity.[2] In just a few weeks, Congress would pass a sweeping law bearing his name, one that criminalized mailing anything to do with sex. “An Act of the Suppression of Trade in, and Circulation of, Obscene Literature and Articles of Immoral Use” included not just pornography and sexual material, but also personal correspondence, educational pamphlets, contraceptives, and items related to abortion.[3] To enforce this sweeping new law, Comstock was appointed Special Agent of the Post Office and endowed with the power to search the mail, seize obscene items, and make arrests. He would soon proudly declare of his accomplishments: “I have endeavored to raise a legal barrier between the youth and this hydra-headed monster of Obscenity.”[4] He was not yet thirty years old.[5]

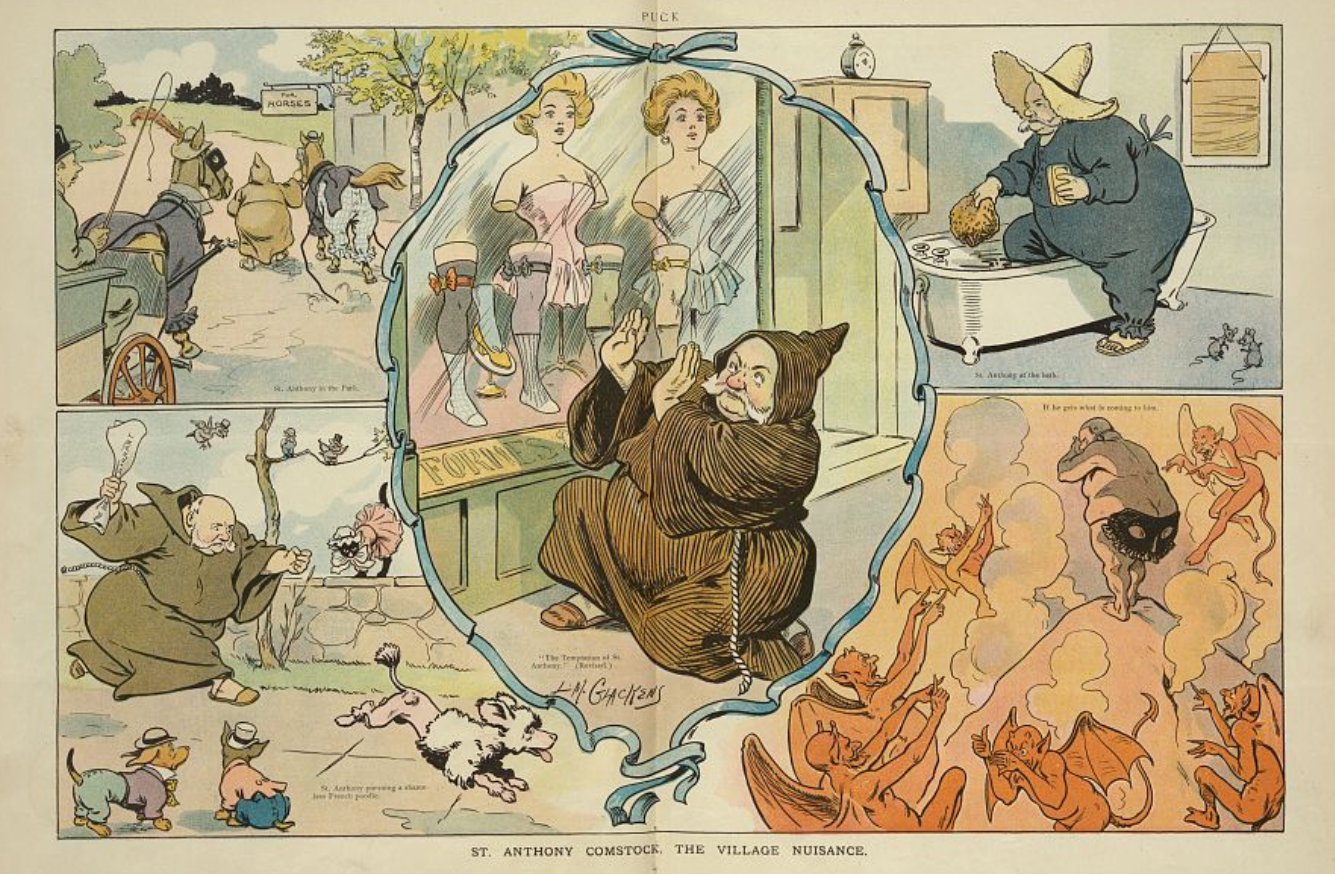

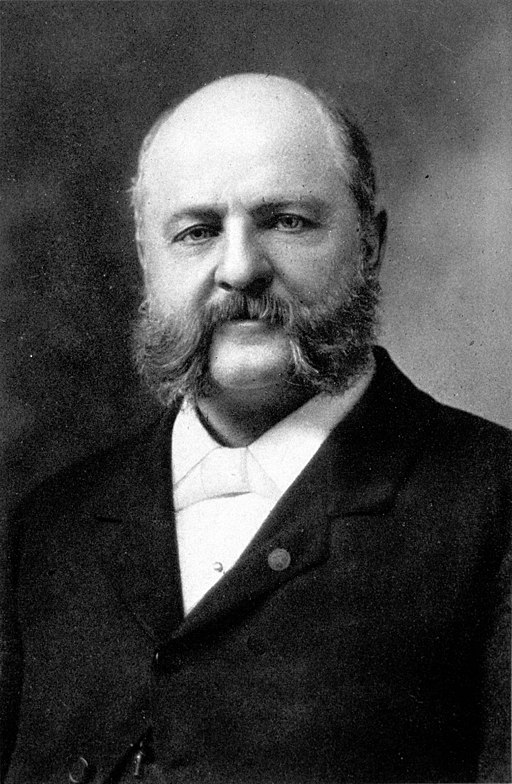

This blog series aims to provide vital historical context for those seeking to understand the modern revival of Anthony Comstock and his namesake law. The Comstock Act has never been repealed and remains part of Sections 1461 and 1462 in the United States Code, although many Americans have little to no idea about the details of this law, if they have even heard of it. Anthony Comstock himself seems like an odd joke today: a repressed, puritanical, anti-sex reformer and a relic of a bygone past (Figure 1). And yet, because the act has been revived as a strategy for limiting access to reproductive healthcare, Comstock is no joke. Some see the statute as a pathway to banning abortion and other reproductive care, which would effectively jettison any need for new Supreme Court abortion rulings or congressional legislation.[6] As scholars of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era, we are uniquely situated to intervene in this dialogue and ensure that contemporary conversations are based on accurate information. We present this series not as an exhaustive account of the Comstock Act and its architect, but as an opportunity to highlight the context in which this law, which holds so much potential relevance for our present, was created, enacted, enforced, and challenged. We also hope that these blog posts will stimulate further scholarly and public conversations around this long history of regulating reproductive rights and how it became entangled with other social anxieties.

Comstock’s biography only begins to explain his lifelong obsession with eradicating obscenity. Even for someone from the heart of Puritan New England, Anthony Comstock was exceptionally pious and prudish. One of ten children, he was born in New Canaan, Connecticut, in 1844 to Congregational Church members Thomas and Polly Comstock. They owned a sawmill and farm, and, although initially prosperous, his father declared bankruptcy when Anthony was just five years old. When he was ten, he arrived home from school to find his mother dead from “flooding,” or hemorrhage during childbirth.[7] Only a few years later, his father abandoned Anthony and his surviving siblings, moving to England and marrying a woman thirty years his junior.[8] After his elder brother died at the Battle of Gettysburg in 1863, Comstock enlisted in the Union Army. Contrary to his later claims, Comstock never saw combat. Instead, his regiment was stationed for the remainder of the Civil War in South Carolina and Florida, where Comstock was bored and uncomfortable with his fellow soldiers, who clearly disliked him.[9] Perhaps this was because he was the kind of man who once made a performative ceremony of pouring his daily ration of whiskey on the ground and reprimanding his compatriots for their drinking, carousing, and sharing of dirty pictures.[10]

During his time in the army, Comstock had felt lost and aimless. After moving to New York City in 1867, however, he found order in a new job, a new family, and a new mission. While working as a dry goods clerk, he was horrified at his co-workers’ (like his fellow soldiers’) consumption of pornography and familiarity with prostitutes. On his own, he began raiding shops that sold pornographic books and items and became more involved with the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA). Together with YMCA officials, he formed the Society for the Suppression of Vice (SSV), hanging a picture of himself in the new offices on Nassau Street.[11]

Soon, the YMCA and Comstock began working on the idea of a federal obscenity law. In this series of blog posts, Andrew Wender Cohen shows how Comstock’s campaign began during the election of 1872 as a political reaction to the radicalism of the post-Civil War period. His wealthy evangelical backers in New York City openly wanted the federal government to enforce individual morality rather than protecting Black civil rights and collecting tariffs to pay war debts. Lauren MacIvor Thompson also illustrates the confusion that Comstock’s legislation created in Congress during the winter of 1873. Originally written with a medical exception that would have allowed licensed physicians to prescribe contraception or abortion care, the removal of this language would create complex enforcement issues for appellate courts.[12]The codified statute, however, applied widely to the “obscene, lewd, lascivious,” “immoral,” and “indecent” and restricted the mailing of “any drug or medicine, or any article whatever, for the prevention of conception, or for causing unlawful abortion.”[13]

The statute handed Comstock all the power he needed, and “[o]n the wings of his new authority, [he] swooped jubilantly down upon the malefactors.”[14] He spent the rest of 1873 “on a rampage of trips,” traveling some 23,500 miles by railroad.[15] Even if Comstock fashioned himself as the nation’s chief vice crusader, he soon recognized that implementing his vision depended upon the investment of other government forces and private organizations, such as his key ally, the YMCA.[16] Perhaps most significantly, many states in the late nineteenth century enacted or revised obscenity laws to complement the new federal provision. Many of these “little Comstock laws” echoed the federal language but, rather than target only mailable matter, often criminalized a wide range of content and behavior. The breadth and diversity of these state statutes further muddled the legal definition of “obscenity” and turned it into a crime that violated a tangled web of state-federal jurisdiction. The details of the legislative and public debates surrounding the laws’ passages remain an important subject for further study.[17]

Bolstering this legislative campaign, Comstock’s New York SSV worked alongside sibling societies in other major cities, including Boston, Chicago, and San Francisco.[18] Magdalene Zier spotlights the Western Society for the Suppression of Vice and its leader, Robert W. McAfee. Zier’s post illustrates the important role that these regional groups played in expanding and enforcing obscenity laws beyond Comstock’s East Coast orbit. In addition to male-dominated anti-vice societies, women’s groups – especially the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) – played a central role in anti-obscenity activism and in carrying the push for purer popular culture into the twentieth century. However, central to the WCTU’s social purity efforts, as well as some of the male-dominated anti-vice groups’ agendas, was a critique of the sexual double standard and male sexual licentiousness.[19]

As the posts in this blog series illustrate, Comstock spent his career, from 1873 until his death in 1915, using his federal mandate, extensive network, and outsized reputation to target abortion providers, birth control advocates and merchants, purveyors of erotic material, exhibitionists, scammers, gamblers, lottery operators, modern artists, and other individuals of whom he simply disapproved. Comstock’s expansive agenda yielded arrests of nearly four thousand people – “enough to fill a passenger train of sixty-one coaches” – plus the seizure of “160 tons of obscene literature,” photos, cards, “rubber articles,” pills, and powders.[20] Though he did arrest many men, his most famous targets were outspoken women, including, as Allison K. Lange’s and Nicholas L. Syrett’s posts illustrate, Victoria Woodhull and Madame Restell.[21] Lange demonstrates that Woodhull and Comstock battled to define visual debates about women’s rights and sexuality. Woodhull defied gender norms through her photographic portraits and engravings in popular illustrated newspapers. These images won fame for her and her ideas but also made Woodhull and conversations about women’s rights the target of Comstock’s policing efforts. Syrett’s piece explores Comstock’s attitudes toward abortion via a case study of the arrest of nineteenth-century America’s most well-known female physician and abortion provider, Madame Restell. Syrett argues that Comstock objected to abortion because he believed it encouraged illegitimate sex and allowed married women to opt out of motherhood.

Comstock’s arrest records and writings also testify to his xenophobia and antisemitism, as well as an obsession with maintaining a culture of sexual purity that was built on protectionism of white middle-class women. Historians have examined Comstock’s prejudice against immigrants, especially Jewish immigrants, which he made explicit in his case ledgers, but there is more research needed to fully unpack the racial and religious biases that drove Comstock’s crusade and America’s embrace of it in this period.[22] The experiences of women of color have long been shaped by gendered violence, eugenic concerns about reproduction, and the ongoing forces of colonialism, but it is unclear how much the Comstock laws directly impacted them. It seems that parallel structures such as federal Indian policy, burgeoning immigration regimes, and the white supremacist violence that dismantled Reconstruction policies targeted people of color to a much greater extent than did Comstock.[23] Further research is thus required on the Deep South, Southwest, and Pacific Coast, to interrogate how Comstock laws interacted with other systems policing sexual and racial purity, such as segregation and anti-miscegenation laws, and with forms of legal and literal violence that persecuted immigrants and people of color for deviating from a standard of propriety rooted in xenophobia and racism.[24]

Comstock’s final target, ironically, was a white man. William (Bill) Sanger, Margaret Sanger’s husband, was arrested for handing out her birth control pamphlet, “Family Limitation.” On the eve of Bill’s trial, Comstock had just arrived back in New York after traveling to San Francisco for the International Purity Congress, returning with a cold that had developed into pneumonia. He rallied from his deathbed, however, to participate in the trial.[25] Bill told the court, “The obscenity laws, State and Federal, as administered by Comstock and his inhuman and ignorant censorship, have driven the mother of my children into exile, separated her from her children now for almost a year, and caused untold hardship to her and to me.”[26] Comstock’s prosecution of the Sangers is well-known and has shaped much of the public understanding of the Comstock Act. Kimberly Hamlin’s post gives readers a new glimpse of this story and the “Family Limitation” pamphlet, along with other key primary sources and artifacts, to illustrate for readers and teachers how these historical texts can help us better understand (and teach) Comstock today.

Anthony Comstock died in 1915, but the Comstock laws did not die with him. A series of significant court cases over the following fifty years testified both to the persistence of restrictive obscenity laws at the state and federal level and to growing resistance. Critics of Comstock struggled to mobilize a cohesive opposition movement during his lifetime, but advocates of free speech and of reproductive freedom gathered momentum in the late 1910s and 1920s.[27] Finding legislators unreceptive to pleas to repeal the Comstock laws, birth control leaders Margaret Sanger and Mary Ware Dennett turned to the courts.[28] A string of test cases in the 1930s succeeded in constraining the reach of the federal Comstock law, carving out protections for contraception and fueling the emerging civil liberties movement.[29] For example, in United States v. One Package of Japanese Pessaries (1936), the Second Circuit emphasized the necessity of narrowly construing the Comstock Act and held that Congress could not bar the shipment of contraceptives ordered by licensed physicians for their patients’ health and well-being.[30] While some states echoed federal courts’ approach, other states preserved restrictive obscenity laws.[31] Fifty years after Comstock’s death, the Supreme Court in Griswold v. Connecticut (1965) struck down Connecticut’s ban on contraception and asserted married couples’ fundamental privacy right to use birth control.[32] Then, in Eisenstadt v. Baird (1972), the Court took aim at Massachusetts’s lingering law and extended the Griswold principle to unmarried individuals.[33] The Court’s intervention coincided with legislative action: Congress in 1971 removed language about contraception from the Comstock Act.[34] In the same years, the Court reconsidered the legal definition of obscenity in Roth v. United States (1957) and Miller v. California (1973). Even as the Court confirmed that obscene materials fall outside the First Amendment’s protections of free speech and thus can be subject to criminal consequences, the Court sought to modernize the sweeping standard of obscenity that prevailed in Comstock’s day and develop a test seemingly focused more on commercial pornography than on reproductive healthcare.[35]

The history of Comstock has many facets, and the legal complexities of modern obscenity law remain in flux. We hope the posts in this blog series will be useful in providing an overview of the important historical themes present in a potential Comstock Act revival. Our work offers a cautionary note to the argument that the Comstock Act should play a future role in how the United States grapples with reproductive rights law. All too often, arguments for the Comstock Act’s contemporary resurrection are ahistorical, resting on modes of interpretation that seek to strip the statute’s language from its historical context. If the Comstock conversation is here to stay, we need to take seriously the circumstances in which the law was passed, the messiness of its enforcement, and the fierceness of resistance to it.