By Dr. David I. Macleod

October 28, 2024

The 2024 Republican platform blames President Joe Biden’s administration for “Raging Inflation.” Technically, inflation in the sense of currently rising consumer prices has declined. Yet the cost of living remains substantially higher than voters remember from five years ago. And this—popularly termed “inflation”—is the point of attack.

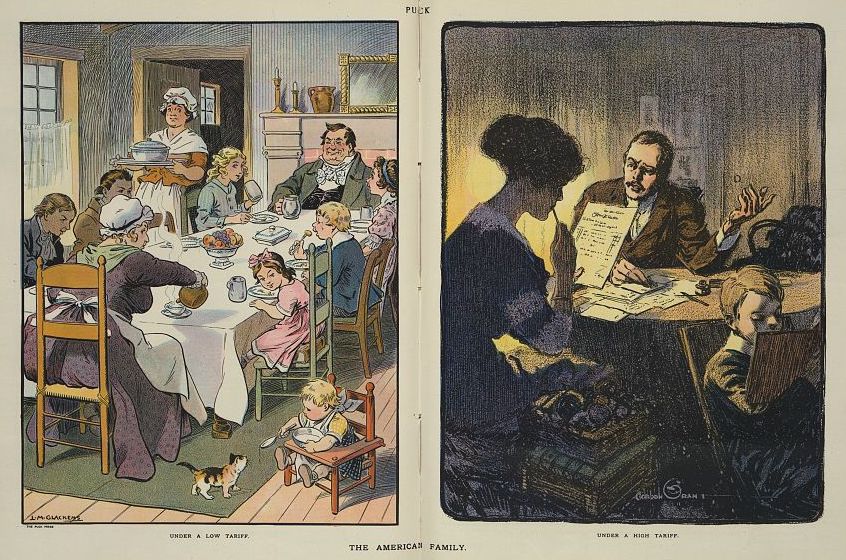

A century ago, the same issue troubled presidential administrations during the 1910s and defied ready remedy. Apparently, some popular anxieties and political responses are hardy perennials. Charges of price gouging abounded. Like Biden and Vice President Kamala Harris, Woodrow Wilson’s Democrats blamed large corporations. They also prosecuted smaller wholesalers and retailers. Tariff levels were fiercely debated—low rates to enhance competition (then a Democratic position) versus high tariffs to protect high-wage American industries and jobs (then and again today a Republican preference). Current Democrats are conflicted and merely warn that blanket high rates will spur inflation. Donald Trump promises lower prices but touts high tariffs as a cure-all for industrial and budgetary problems, ignoring their inflationary potential. Grocery prices remain a leading irritant today but mattered even more then, since food bulked larger in household budgets—41 percent of wage workers’ household spending according to a 1918 survey. Whereas economists today strip out volatile food and fuel prices to find core inflation, throughout the 1910s the federal government’s measure of the cost of living simply averaged the retail price at city stores of a small, meat-heavy list of food items.

The federal government’s regulatory involvement in the economy has grown greatly since the 1910s, even allowing for makeshift expansion during World War I. Federal agencies such as the Justice Department had skeletal staffing by today’s standards. Unlike today, the Federal Reserve Board that began operation in 1914 had no mandate to maintain stable prices, little economic expertise, and limited independence from the president’s administration. Until early 1920, it pursued liberal credit policies that monetarists consider inflationary. The incongruities of fiscal politics, though, resembled those of today. A Democratic administration tolerated massive borrowing—to meet wartime needs then and a pandemic emergency recently—while Republicans condemned as inflationary actions they might well have taken themselves (and did during Trump’s administration). Unlike in Wilson’s era, today’s Federal Reserve Board bears much of the responsibility for curbing inflation. Yet politically, the president’s administration still faces most of the criticism when consumer prices have risen sharply. Then and now, the budgetary pressures of competing policy needs and the sheer difficulty of lowering prices virtually guarantee voter discontent.

From 1897 onward, high-tariff Republicans controlled the federal government. Meanwhile, a wave of corporate consolidations around 1900 created behemoths like United States Steel with awesome pricing power. Then in 1910, after years of stable or slowly rising consumer prices, a 4.6 percent increase spurred widespread meat boycotts and a spate of journalistic alarmism that established the high cost of living as a leading political issue. Come fall, the incumbent Republicans lost fifty-six seats and control of the House of Representatives. Newspapers blamed Republican import tariffs and the high cost of living for the “Republican overthrow.”[1] President Taft predicted unhappily to a fellow Republican that without “lower prices in the necessities of life . . . we are going to be beaten in the next presidential election.”[2]

Although the Taft-Roosevelt split virtually guaranteed Wilson’s victory, historians remember the 1912 election for debates on two issues: high tariffs and corporate monopolies. Animating concern over both was the high cost of living. Taft had little to offer beyond having filed antitrust suits. Wilson blamed tariffs that shielded monopolistic, price-gouging corporations. Quotably, he charged, “The high cost of living is arranged by private understanding.”[3] Running as a Progressive, Theodore Roosevelt declared expansively, “There can be no more important question than the high cost of living necessities.”[4] A tariff protectionist, Roosevelt also derided efforts to break up corporations, arguing that petroleum prices rose after Standard Oil’s separation into regional firms. Instead, he proposed regulating corporations and curbing middlemen’s exactions. As consumers, urban voters moved away from the Republicans’ Taft and toward Roosevelt and secondarily Wilson. Overall, Wilson outpolled Roosevelt, Taft finished third, and Democrats won control of the Senate.

Wilson made tariff reduction 1913’s first legislative goal. New rates were broadly lower, and most meat and livestock, wheat, flour, milk, and potatoes entered duty-free, but supplies did not flood in immediately and the war soon disrupted trade patterns. Taking aim at corporations, Democrats passed the Clayton Antitrust Act, which supplemented the Sherman Antitrust Act by specifying forbidden practices. The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) Act authorized a presidentially appointed commission to order corporations to cease unfair methods of competition but depended on courts even more pro-business than today’s for enforcement.

The Biden administration and Harris campaign have also attacked monopolies and blamed inflation on corporate price gouging. Arguably, the pharmaceutical industry serves as today’s prize miscreant. For Wilson’s era, it was what contemporaries called the Meat Trust: Swift, Armour, and three lesser firms that dominated American meatpacking. Stock raisers, hog farmers, and consumers believed that this group underpaid for cattle and hogs, while supplying retail butchers at exorbitant prices. On matters of collusion and price the packers proved impregnable. Even during the World War I emergency, the packers’ complex accounting defeated federal efforts to limit their profits. Pork prices soared 42 percent–and other meats even more–in nineteen months of war. When in 1919 a federal grand jury in Chicago refused even to indict the meatpackers, Wilson’s attorney general settled for a tepid (and often violated) consent decree that required divestment of stockyards and some other assets but said nothing about price restraint. Today little has changed beyond a shift toward poultry and the names of the dominant corporations.

Due to wartime and postwar inflationary pressures, US consumer prices doubled between 1915 and mid-1920. Luckily for Wilson, the first huge upsurge came late enough to remain a secondary issue until late in the 1916 campaign. Nonetheless, the Republicans’ Charles Evans Hughes almost won, carrying most urban-industrial states. Commenting on the agrarian-urban divide, an editor observed, “In the one section, getting $1.75 a bushel for wheat has been an argument for Democracy; in the other section paying $12 a barrel for flour has been an equally cogent argument against it.”[5] In the campaign’s final week, New York City papers carried large ads focused on “The Broken Promise” of Democrats to reduce the cost of living.[6] One such ad literally underlined that “your money doesn’t buy as much as four years ago.”[7] Another, from Maysville, Kentucky, itemized increased food prices, then parodied a famous Wilson utterance: “WE ARE NOT TOO PROUD TO EAT.”[8] Wilson eked out a victory by focusing on other issues, while House Democrats dropped into a tie with Republicans.

Although Wilson’s war message urged Congress to avoid vast, inflationary loans, enormous costs and reluctance to tax led congressmen to embrace them. Just one-fifth of households paid 1918 income tax and effective rates reached 10 percent only at $20,000 income (over $400,000 today). Business taxes brought in more, but in the fiscal year ending June 30, 1919, the federal deficit exceeded $13 billion. In theory, patriotic bond drives covered much of the shortfall and reduced consumer spending. Although millions of purchasers contributed modest sums, receipts came primarily from the well-to-do and banks. And purchasers were encouraged to borrow the cost from banks, so they could continue spending. The US money supply grew more than 12 percent a year between August 1914 and May 1920, far outstripping growth in GNP. Furthermore, Wilson’s wartime administration suspended antitrust litigation to secure business cooperation. The FTC busied itself with reports on collusive pricing of commodities such as gasoline and meat, which a postwar Republican Congress subsequently ignored.

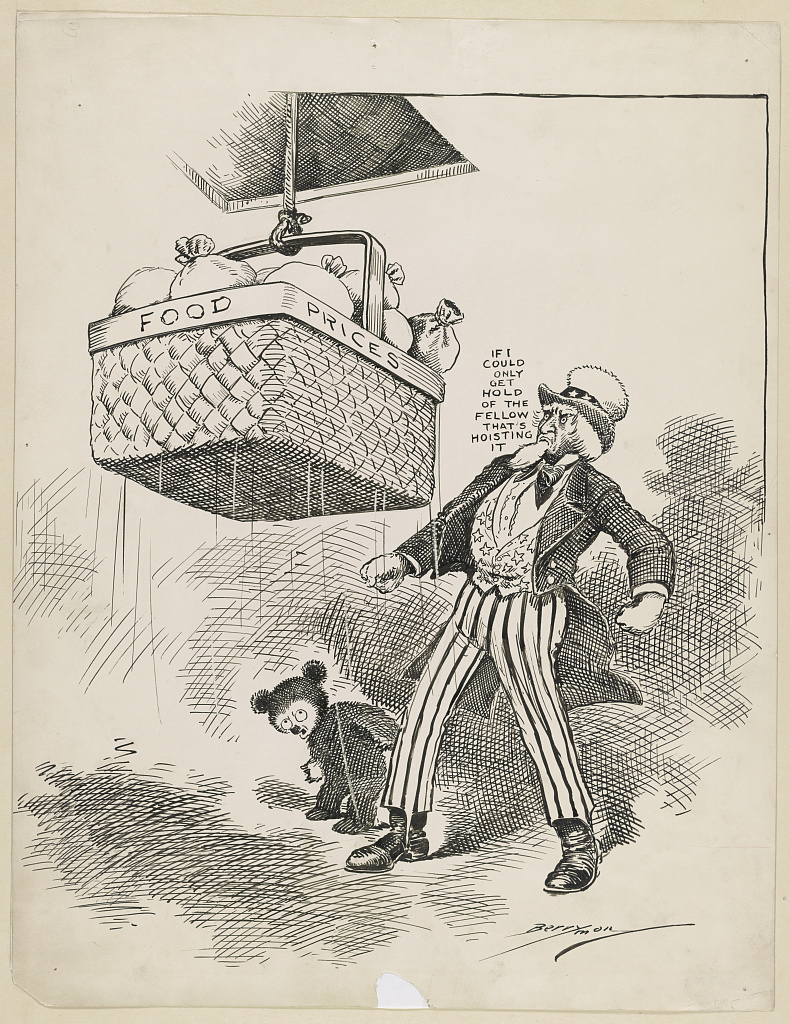

Inflation did not end with the war. After a brief lull, prices surged again in late spring 1919. A bit like today, discontent with inflation fed off impatience with the president’s foreign concerns. In May, members of the Massachusetts legislature cabled Wilson in Paris, “The citizens of the United States want you home to help reduce the high cost of living, which we consider far more important than the League of Nations.”[9] Addressing Congress in August, two months before his crippling stroke, Wilson urged unconvincingly that ratifying the Versailles Treaty would curb inflation and called for measures to monitor and control prices. A Republican Congress enacted few beyond imposing penalties for charging “unreasonable” prices for food or clothing.

Neither the administration’s lead inflation fighter, Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer, nor the Federal Reserve Board did much to curb the price surge. Palmer launched a highly publicized campaign against profiteers, but for lack of personnel, the Justice Department targeted mainly small fry. Federal prosecution netted just ninety-nine convictions by late 1919, mostly sugar wholesalers and clothing retailers, and convictions waned in 1920. Through 1919, the reserve board dutifully backed the administration’s low-interest-rate policy to reduce the cost of government borrowing. Eventually, panicked by shrinking reserve ratios, a divided board voted four to three in January 1920 to raise discount rates abruptly from around 4 percent to 6 percent and three to two in June to boost some rates to 7 percent. Still, the money supply shrank less than 2 percent in 1920 before contracting sharply amid recession in 1921.

As economies worldwide slowed and Europeans found competing food sources, prices for US agricultural exports cratered in autumn 1920, collapsing domestic commodity prices in tandem. But falling wholesale prices were slow to alter consumer prices and rents kept rising. Living costs for urban workers peaked in July 1920 and declined only 4.5 percent by October. On election day, Democrats confronted double discontent: farmers’ incomes were plummeting, while consumers still faced living costs near their peak.

Democrats had no obvious economic defense. Hoping to campaign on US entry into the League of Nations, they were overwhelmed. Republican Charles Dawes scoffed: “What our people are chiefly interested in is the reduction of the high cost of living and restoration of normal conditions of life.”[10] The Republican platform charged Democrats with financing the war “by a policy of inflation,” floating massive low-interest loans whose buyers borrowed their payments at equally low rates. Further, Democrats had spurred inflation through “gross expansion of our currency and credit.”[11] Conveniently, Republicans could heap blame for inflation on past Democratic mistakes while promising little going forward beyond frugal government and a vague normalcy. (Tacitly, this implied restoration of prewar conditions.) The disgruntled editors of The Woman Citizen summarized the campaign: “‘Turn out the Democrats. They have caused high taxes, high rent and high cost of living,’ shouts one great party. . . . The other, responding in desperate tones, cries back, ‘If you do, we get no League of Nations.’”[12] Immigrant anger at the war and the peace settlement hurt Democrats. A New York reporter found Italian-born voters fuming over Italy’s frustrated postwar claims; but he was assured “that the high cost of living was the controlling issue.” Sugar prices particularly rankled.[13] Lest complacent supporters fail to vote, the Republican National Committee placed late-October ads in small-town newspapers to restoke voters’ discontent: “For everything entering into your daily life you are paying an abnormal price—an unprecedented price.”[14] The Democrats’ James Cox lost the presidency overwhelmingly to Warren G. Harding. Democrats also lost fifty-nine House and ten Senate seats.

Economically, there was no soft landing. A deep recession ensued in 1921, with recovery by 1923. Consumer prices then stabilized at levels close to November 1918, far above prewar.

Rising consumer prices consistently harmed the party in power politically. Compared to our recent outburst, Republicans in 1910-1912 faced moderate inflation, but its novelty and their lack of an answer combined with intraparty divisions to cost them control of the presidency and Congress. In power, the Democrats lowered import tariffs (a response unthinkable today) and passed modest antitrust measures to spur competition. Then and now, however, the effect on prices of policies aimed at increasing competition was at best slow for impatient voters. In any case, the war disrupted trade patterns and led the Wilson administration to suspend antitrust litigation and adopt inflationary fiscal policies. Starting in 1916, the war generated inflation more severe than even our worst recent years. The neophyte Federal Reserve Board provided no check on rising prices until its clumsy rate hikes in 1920. Voters’ patience eroded election by election, especially once the excuse of wartime necessity ended.

Attorney General Palmer’s hasty countermeasures in late 1919—ineffectual antitrust action against the meatpackers and scattered prosecution of profiteers—petered out and brought Democrats no benefit. Perhaps Biden-Harris measures against anticompetitive corporate practices and price gouging, undertaken more deliberatively and with better administrative support, will appeal to voters, but they cannot offer the immediate gratification of rapidly lowering prices. As in 1920, the opposition party can stoke popular discontent with high prices while offering no policy response—instead floating deregulation, inflationary tariffs, and tax cuts. Then as now, the dream of restoring “normal” (i.e., long past) prices would require recession or depression.

[1] “Meaning of the Republican Overthrow,” Literary Digest 41 (Nov. 19, 1910): 915.

[2] William Howard Taft to Nelson W. Aldrich, January 29, 1911, series 8, vol. 22, reel 505, William Howard Taft Papers, Library of Congress microfilm edition.

[3] “Wilson Appeals to ‘Awakened Nation,’” New York Times, Aug. 8, 1912, 6.

[4] Theodore Roosevelt, “A Confession of Faith,” Aug. 6, 1912, in idem, Social Justice and Popular Rule (New York: Scribner’s, 1926), 287.

[5] “The Meaning of the Election,” Outlook 114 (Nov. 15, 1916): 597.

[6] E.g., New York Times, Nov. 3, 1916.

[7] “Just Before You Vote,” Sun, Nov. 4, 1916.

[8] Capitalization in original. Public Ledger, Nov. 6, 1916.

[9] “Urge President to Return,” New York Times, May 24, 1919, 4.

[10] Charles G. Dawes, “The Next President of the United States and the High Cost of Living,” Saturday Evening Post 193 (Oct. 2, 1920): 7.

[11] Republican National Committee, Republican Campaign Text-Book, 1920 (New York: The committee, 1920), 85, 87.

[12] “Blessed Are the Bolters,” Woman Citizen, 5 (Oct. 23, 1920): 565.

[13] “European Issues Having Effect on Alien-Born Voters,” New York Tribune, Oct. 16, 1920, 2.

[14] “Harding and Coolidge and Good Government,” in, e.g., Parisian (Paris, Tenn.), Oct. 29, 1920, 3. That year, Republicans carried even Tennessee.

Dr. David I. Macleod

David I. Macleod is Professor Emeritus of History at Central Michigan University and author of Inflation Decade, 1919-1920: Americans Confront the High Cost of Living (Palgrave Macmillan, 2024), from which this essay is drawn.