By Dr. Keith McCall

November 5, 2019

Emancipation introduced massive demographic shifts within the U.S. South, and with them came cultural, social, and political changes. These trends and transformations were driven by the hundreds of thousands of freedpeople who left their places of enslavement and their old neighborhoods to strike out for new locations where, they believed, they could better enact their visions of freedom. The demographic impact of freedpeople’s movements shaped how Reconstruction played out unevenly across the postwar South, and the movements out of the South helped nationalize issues of racial inequality and civil rights in the late nineteenth century. Yet behind these demographic facts lurk a messier and more elusive question for the study of freedpeople’s communities and political strategies: the information networks and geographical knowledge that supported and sustained one of the most significant internal migration movements in U.S. history.

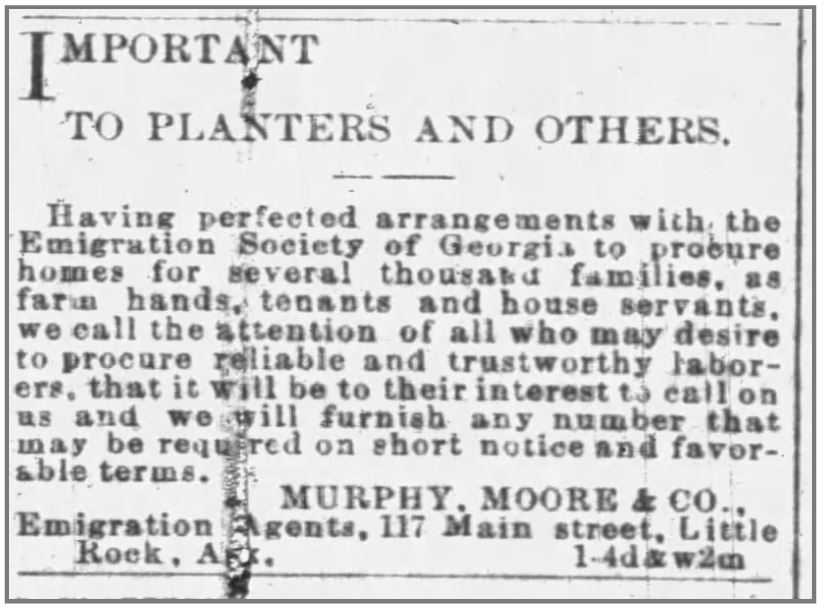

Tracking the overlap of planters’ labor recruitment networks and freedpeople’s kinship networks provides some suggestions about how these networks helped freedpeople collect, assess, and share the geographical information that structured routes of migration. Information was power, and access to geographical information allowed freedpeople to change their world by changing their place in it. While planters used their black workers to recruit additional black workers in the Reconstruction South,[1] freedpeople also used planters’ agents to enact their own plans of migration and to secure their own sense of place. My interest is in parsing these overlapping and intersecting networks of information and to specifically identify the forms of geographical knowledge about routes of migration and potential destinations that were indigenous to freedpeople’s own networks of information. By doing so we can gain a deeper understanding of how the powerful experiences of slavery and emancipation shaped freedpeople’s sense of place and mobility. Historians have emphasized the ways geopolitical knowledge was central to the forms resistance took during slavery.[2] The next step is to realize that many of those geopolitical understandings and pathways of knowledge remained intact during the era of Reconstruction—if anything, they vastly expanded. Freedpeople, on many occasions, set off on migrations only after gathering and considering the information available on their potential destinations, such as expectations of wages and the availability and quality of land. Networks of kinship and community circulated this type of geographical knowledge and shaped freedpeople’s routes of migration.

Distinguishing among the various networks of information and routes of migration can be messy. Because planters’ organized efforts to recruit labor often relied on freedpeople to act as intermediaries, the lines separating white planters’ efforts to recruit labor from the information that circulated through black kinship networks were often murky. Family migrations spread over years, moreover, often involved both individual migrations and ones undertaken in relation to labor recruitment. Freedman Henry Kirk Miller’s parents, for instance, migrated to Arkansas before he did. He remained behind in Georgia and married in 1872 before he and his wife followed his parents in 1873. They did so by signing on with a labor agent. Miller recalled, “A man from Arkansas came [to Georgia], getting up a colony of colored [people] to go to Arkansas to farm….Me and my wife joined up to go.”[3] Regardless of why he chose to work with a labor agent, Miller’s migration was about fulfilling two important aspects of freedom: establishing and maintaining family connections and finding gainful employment. Labor recruitment allowed him to achieve both goals.

Anna King similarly used labor recruiters to make possible a migration that her husband had long desired. King lived in North Carolina after emancipation, but she married a preacher from Arkansas, who tried to persuade her to move across the Mississippi with him. “He always said he was going to bring [me] out to this country [Arkansas]” King said. “He was always tellin’ me ’bout Little Rock and Hot Springs.” King’s husband died before the couple could relocate together, but King kept the idea of Arkansas alive in her geographical imagination, and “when they was emigratin’ folks here, I come.” The opportunity afforded King through organized labor recruitment offered her a way to fulfill the future she and her husband planned, and though she needed the planters’ networks to provide transportation, it was her husband and his geographical knowledge that made Arkansas legible and migration attractive to begin with.[4]

Return migration among kith and kin served a similar function among freedpeople’s information networks: those who had migrated and found employment would return home for visits. Sometimes their mere appearance attested to the promise of distant opportunity. Other times, visitors carried home with them offers of employment from distant planters and tried to convince their friends and family to sign on. “Doc” John Pope, who had been enslaved near De Soto, Mississippi, acted as a labor recruitment intermediary on at least one occasion.

Immediately following emancipation, Pope made his way to Memphis and eventually attended Fisk University, where he studied medicine. In 1881 he went to Biscoe, Arkansas, where his uncle Isaac Pope was farming. And there he remained, except for when his employer “sent [him] back home to get more hands.” He turned to his old community near De Soto and persuaded fifty-two families to sign on to farm near Biscoe, Arkansas.[5] Elvie Lomack found herself in Arkansas as the result of similar labor recruitment efforts. She and her parents were getting along in Tennessee after emancipation, farming for the woman who had owned her mother. One day, “a man [her] mother knowed” came to sign up families to move to Arkansas. He had been in Arkansas two years, and he “come back to Tennessee and, oh Lord, [he told them] you could do this and that, so we come here.”

White observers in regions with high amounts of out-migration worried about the impact of visiting in encouraging more emigration. The Richmond Whig, in 1870, raised the alarm that migration to the Gulf States was depleting Virginia of its black labor force and that short-term visits were increasing the problem:

The Christmas holidays brought many of them back on visits to their families, and all such will probably prove efficient emigration missionaries. Returning with their holiday outfits and supplies of money and full of the novelties of Southern plantation life, they will probably greatly increase the already existing inclination among the colored people of the State to remove southward. If only ten thousand went from among us last year, we may count upon double the number the present year. [6]

Such visits, as Whig’s editor rightly perceived, were key to freedpeople’s information networks.

The Whig saw only the “outfits” and “supplies of money” that visitors brought back to their old communities, but they sometimes also arrived with offers and terms of employment, as Cohen’s research makes clear. Cohen uses the example of George Wiggins and Isham Johnson, who had been enslaved in Virginia and worked on Edward Gay’s Louisiana plantation after emancipation. Wiggins and Isham went to visit their families in Virginia in 1870 and were told “if any of their friends would like to come out with them,” they could make at least twenty dollars a month. Wiggins and Johnson must have found the offer appealing. Wiggins wrote back, “There is a Great Menney people here working for 25 cts per day[.] those people cant live here.” Johnson, too, wrote back, noting that his own family was ready to contract for the Louisiana wages.[7] Their visit home brought not only the appearance of distant opportunity, but also a concrete promise of wages. They acted as both purveyors of geographical information and planter’s agents, and people in their old community trusted Wiggins and Johnson because they knew them and considered them a part of their information network.

Planters did not set the terms of freedpeople’s postwar migrations any more so than did freedpeople’s own desire to establish and maintain kinship networks. Similarly, freedpeople did not need labor agents’ tales of distant abundance to inscribe places on their mental maps—the networks of kith and kin and the visits from those who had already gone to distant places gave many freedpeople detailed, if sometimes impressionistic, cartographies. Indeed, freedpeople’s ability to turn labor recruitment efforts toward their ends demonstrates the sophisticated networks of geographical information among freedpeople. Anne King and Henry Kirk Miller didn’t need a planter’s agent to tell them about Arkansas—their own kinship networks and sources of information had already put Arkansas in their minds as a place to go. They simply needed organized labor recruitment to facilitate the actual move.

The origin of the information King and Miller gathered on Arkansas was direct and immediate, coming from close family members. For many other freedpeople, the sources of geographical information was more vague. Indeed, many of the information networks of postwar black migration remained reliant on an oral culture. Historian Barbara J. Rozek’s work shows that Texas’s postwar immigration promoters strongly believed in the efficacy of the written word, focusing their efforts on published pamphlets to induce migration; freedpeople’s geopolitical communication networks, in contrast, demonstrate the continued power of word-of-mouth networks to shape routes of migration in the postwar South.[8] The existence of these widespread and sophisticated information networks, despite their scant documentation, suggests that the idea of somewhere else was constantly circulating through freedpeople’s conservations, debates, and political consciousnesses. Understanding the geographical knowledge and routes of migration that reshaped the postwar South requires uncovering and understanding freedpeople’s information networks. Only then can we begin to understand migration on their terms, from their perspective.

Dr. Keith McCall

Keith D. McCall is a lecturer in the department of history at Rice University, where he received his Ph.D. in May 2019. His work focuses on freedpeople’s intra-South migrations in the era of Reconstruction, focusing on the intellectual and geographical frameworks that structured both freedpeople’s migratory routes and how white observers understood black migration.