by Lizzie Evens

October 8, 2019

On 10th August 1916, detective Frances Benzecry visited a young woman, Elizabeth Kessler, and her foster mother at their home in the Yorkville neighbourhood of New York’s upper east side. At that time, Kessler was embroiled in an abortion trial in which she accused German nurse Katie Rath of performing a criminal operation on her. On Benzecry’s visit, the sleuth allegedly counselled the informer to “have a heart for the midwife” and suggested “why don’t you drop the whole thing and don’t be bothering about it.” This intervention led the District Attorney to indict Benzecry on the charge of perjury.[1]

Benzecry’s intercession in the case is all the more intriguing because, for ten years prior, she worked as an investigator for the New York County Medical Society, a professional organisation for the city’s “regular” physicians.[2] The Society was also a quasi-state actor and a regulatory body that sought to obtain a monopoly in the medical marketplace over “irregular” doctors—hydropaths, naturopaths, Christian Science healers, “beauty doctors”—and midwives. It was detective Frances Benzecry’s task to police the boundaries of medical professionalism in the early-twentieth-century city.

Professionally known as Belle Holmes, between 1905 and 1916 Benzecry led the Society’s efforts to rid New York City of unlicensed medical practitioners. In the words of one newspaper feature, Benzecry investigated “fortune tellers with wonderful charms, unguents, herb teas, and lucky pieces; prophets with direct messages to go a-healing from the blue empyrean itself; practitioners of strange cults, with names especially coined for the occasion; practitioners who are shielding their own irregular practices by the dishonored cloak of graduate physicians.”[3] Securing evidence against these practitioners was complex. When a patient complained to the County Medical Society, they often hesitated to give their name and declined to take part in legal proceedings. Therefore, the physicians looked to a team of female investigators, of whom Frances Benzecry was the most prolific, to collect the evidence necessary for conviction.

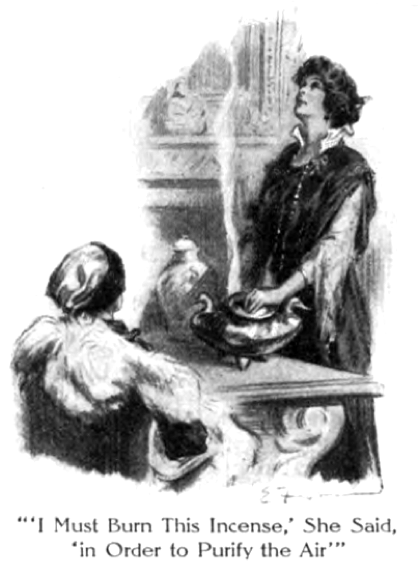

The “much medicated” Benzecry’s method entailed her working undercover, posing as a patient seeking a remedy for a faux ailment, and submitting to an unorthodox treatment. The Medical Society then presented the information she gathered to the New York Police Department, who arrested the irregular practitioner and labelled them a “quack.” In turn, the police donated the proceeds of the fines back to the Society. On occasion, Benzecry even partnered with Isabella Goodwin, the first female police detective in the US. Benzecry conducted countless investigations according to this procedure and described in a Ladies Home Journal feature: “I have been baked, hypnotized, bathed in strange unguents, massaged and pulled and slapped; I have been electrified in a hundred different ways; I have been kept in dark rooms during ‘silent treatments’; and I have taken weird concoctions guaranteed to cure me of ills I never possessed.”[4]

For women in policing, journalism, and social reform, undercover work offered a means of personal advancement and professional acclaim in the early twentieth century. Women’s affinity for investigative work drew upon traditional feminine powers of observation, meanwhile their penchant for disguise stemmed from the association of femininity with both malleability and deception.[5] According to the autobiography of early New York policewoman Mary Sullivan, women often investigated quacks because “feminine patients are less likely to excite suspicion” as women were the majority of “irregular” doctors’ patients and a minority of urban regulators. Frances Benzecry therefore extended the Society’s purview into new spaces that were otherwise beyond the reach of its membership, comprised mainly of male physicians. Mary Sullivan also stressed the skilled nature of this daring work. During her first investigation of an irregular doctor, the policewoman made the mistake of complaining of a stomach ailment and as a result was given nauseous medicine to ingest ; “a tactical error which I haven’t since repeated.”[6] Benzecry availed herself of such strategies, alongside her talents for disguise, to extend the Medical Society’s surveillance into the feminine spaces of irregular doctors and their patients.

While accounts of “female sleuths” titillated newspaper readers, those targeted by the Society did not share their whimsy. Unsurprisingly, Benzecry earned the ire of irregular practitioners, and gender shaped critiques of Belle Holmes. Following an investigation, naturopath Benedict Lust targeted Benzecry, rather than the Society who employed her, with his vitriol. He branded her “mean and dirty” and a “disgrace to womanhood” who was “enough to make any man boil.” Lust went as far as to accuse Benzecry and other female investigators of seducing those they investigated, while another arrestee suggested she was motivated by financial gain and openly accepted bribes.[7]

The biggest challenge to Benzecry’s reputation, however, was Elizabeth Kessler’s 1916 abortion case and the accusation that the sleuth committed perjury. By this time, she had left the service of the Medical Society and performed private detective work. It is nonetheless surprising that Benzecry intervened to protect the alleged abortionist, given that the criminalization of abortion and demonization of midwives were intimately tied with regular physicians’ pursuit of professionalization, as James Mohr and Leslie Reagan have shown.[8] Given her work as an agent of medical surveillance and her reputation as an enemy of irregular physicians, it is unclear why the detective sought to protect nurse Katie Rath. Benzecry alleged that she approached Kessler because she believed it was the woman’s foster mother, rather than the nurse, who had induced an abortion and suspected that the pair wished to blackmail the midwife. The truth of the situation is unclear, however, nurse Rath had a prior conviction for attempted abortion in 1915 for which she lost her midwifery license. Perhaps, the detective sought to protect the trained nurse because she believed that her services were important, while those of irregulars were not. Or maybe, Benzecry found gender solidarity with Rath and the needs of her female patients.

In this, Benzecry was an outlier—many other women with regulatory power did not intervene to protect abortion services in this period. For instance, some female physicians furthered the association of midwifery with unprofessionalism and criminality to distance themselves from the criminal abortion and claim membership in the medical establishment. Meanwhile, as I argue elsewhere, NYPD policewomen mirrored Benzecry’s undercover tactics to control midwives suspected of practicing abortion; the same women who the medical detective seemingly sought to protect.[9] Therefore, as well as offering a rare glimpse at the nuanced reproductive politics during the era of criminal abortion, Frances Benzecry’s detective work showed how the aims and power of the lofty institutions of the NYPD and New York County Medical Society were distilled and fractured in her career of medical surveillance.

Lizzie Evens

Lizzie Evens is a PhD candidate and Wolfson Scholar at University College London, where her thesis ‘Regulating Women’ examines how early women in medicine and policing gained professional power by extending surveillance of other women’s sexuality and reproduction.