By Dr. Anya Jabour

July 13, 2021

This is the first in a series of blog posts on women’s history and the long Progressive Era, honoring the legacy of the late Elisabeth Israels Perry. Perry served as SHGAPE President from 1998-2000 and had a long and distinguished career that highlighted women’s political activism in GAPE and in the “long Progressive Era” that stretched into the 1920s and 1930s. This blog series coincides with the July issue of the Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era, which includes a roundtable (now available to subscribers online) on Perry’s After the Vote: Feminist Politics in La Guardia’s New York (2019). Read the other posts in the series here and find the CFP here.

An “Adamless Eden for Female Offenders”?

In 1912, journalist Ida Tarbell wrote an admiring article about Katharine Bement Davis, the first superintendent of New York’s Reformatory for Women at Bedford Hills (commonly known as Bedford Reformatory). In keeping with the aims of women’s reformatories, Tarbell explained, Davis had made Bedford a site of rehabilitation rather than retribution. With “Good Will to Women” and “an apparently exhaustless source of cheerful energy,” Davis had instituted a program of schoolwork, physical exercise, domestic chores, religious instruction, and “a varied program of dances and entertainment.” Comparing the reformatory to a boarding school rather than a prison, Tarbell concluded that Bedford was “as hopeful an institution as there is in this country.”[1]

By the time Tarbell penned her laudatory account, however, Davis—like other directors of female reformatories—had become disillusioned by what she saw as an increasing proportion of “incorrigibles” among her inmates. In her quest for explanations for this “most difficult class” of offender, she equated immorality with criminality and moral failings with mental incapacity.[2] Adopting prevailing eugenic theories about intelligence testing and heritable criminality, she ultimately recommended the permanent institutionalization of those she deemed irredeemably immoral.

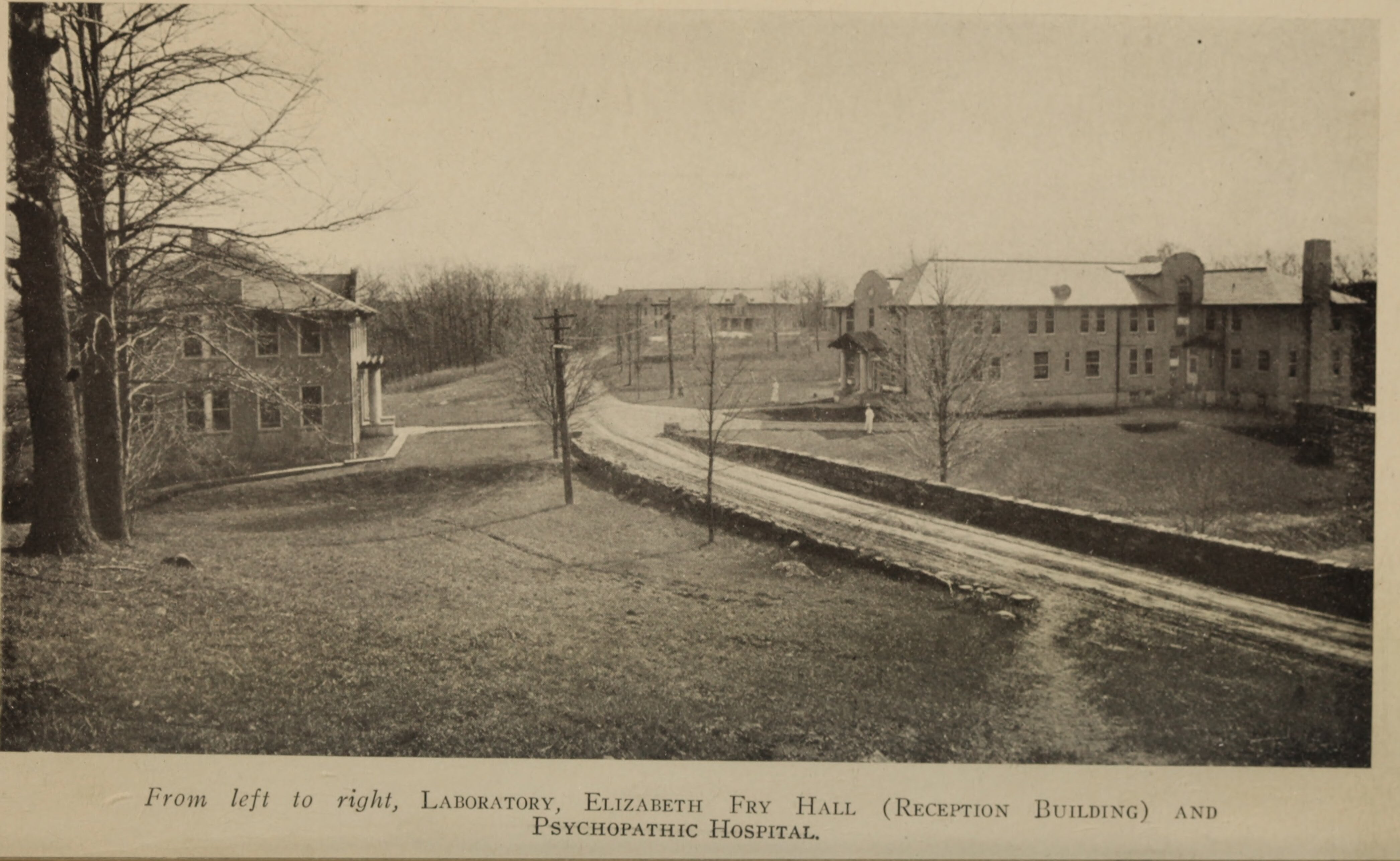

An examination of Davis’s tenure at the Bedford Reformatory offers important insights into women’s role in the carceral state. A quintessential “New Woman,” Davis was a member of the first generation of college-educated women who pioneered new professions. Like many of her contemporaries, even after earning her Ph.D. from the University of Chicago, she found that higher education did not necessarily translate into professional opportunities. Instead of pursuing a career in academia, she entered the new field of social work, focusing on prison reform. From 1901 through 1913, she directed the Bedford Reformatory, which one newspaper dubbed an “Adamless Eden For Female Offenders.”[3]

When Davis first assumed her post, she was determined to make New York’s first female reformatory a shining example of penal reform. Before taking the job, the former schoolteacher announced: “My only interest in accepting the superintendency is my desire to make an educational institution of it. I have no desire to be the warden of a prison.” Drawing on her own college experience, the Vassar alumna explained that her goal was to make Bedford “to its inmates what an ideal college is to a college student, a stepping stone towards a happier and more useful life.”[4]

At Bedford, Davis not only implemented a plan to “re-educate” female offenders, but also hired a cohort of female professionals to assist her in her work—which ultimately included testing and classifying inmates. At the same time that Davis and her colleagues helped to construct the carceral state and carve out a place for female professionals in it, they built their careers at the expense of working-class, Black, and immigrant women categorized as mentally and morally inferior and institutionalized against their will. Davis’s career in penal reform reveals that women played a central role in creating the carceral state in Progressive-era New York, with profound implications for contemporary American society.

Reforming Women

Bedford owed its existence to the nineteenth-century female reformatory movement, which justified women’s leadership based on Victorian assumptions about elite white women’s moral superiority and their commitment to uplifting their fallen sisters. These ideas persisted even as the next generation adopted new ideas about sexuality and morality. Davis’s contradictory views reflected these shifting dynamics. In public lectures, Davis called for a single sexual standard, which she defined as “the so-called woman’s standard, imposing chastity and continence outside of the marriage relation on both men and women.” However, unlike some feminist reformers in both the US and the UK, Davis advocated aggressively prosecuting suspected prostitutes. “I do not agree that if one innocent girl is arrested on the street it discredits our whole system,” she pronounced. Indeed, she insisted that she had never encountered an innocent defendant.[5]

Ironically, while Davis condemned the sexual double standard, her charges found themselves at Bedford because of it. Bedford’s inmates—girls and women between the ages of sixteen and thirty—were confined for a variety of reasons, ranging from minor offenses to serious crimes. According to Davis, while only 40 percent had been arrested as “common prostitutes,” the vast majority (nearly 70 percent) had been arrested for “public order” offenses, ranging from loitering to “waywardness.” These imprecise categories meant that women often were arrested and imprisoned not only for engaging in sex work but also for other behaviors —such as public intoxication or nonmarital sex—that were not technically crimes, but which violated prevailing standards of feminine propriety. Meanwhile, men’s sexual behavior was neither stigmatized nor criminalized.

Unperturbed either by the vague definitions of women’s offenses or by the gender-specific application of laws criminalizing prostitution, Davis opined that “a very large proportion of those convicted of disorderly conduct and public intoxication were immoral women.” Indeed, she unequivocally asserted that “the fundamental fact” about “women delinquents” was that they were “women who lead sexually immoral lives.”[6]

Wayward Women?

It is notoriously difficult to study inmates of institutions like Bedford. Except for chance discoveries—like letters written by inmates—written records rarely reflect the perspective of the institutionalized. However, extant sources offer a statistical profile of Davis’s charges, as well as some clues about what led them to Bedford.

Annual reports show that the typical Bedford inmate was the daughter of a working-class family beset by tragedy and poverty; fewer than half had both parents living, and surviving parents held poorly paying jobs. Prior to incarceration, the majority of inmates either contributed to the family economy or supported themselves. With little education or training, most worked as domestic servants or factory operatives. While most inmates were white, native-born women, a significant minority were not. During Davis’s tenure, up to one-fourth of Bedford’s population was foreign-born; by the end of her term, nearly one-fifth of Bedford’s inmates were African American.

Individual profiles complicate Davis’s characterization of Bedford’s inmates as sexually deviant. Some experienced sexual assault or engaged in survival sex. For instance, Davis told the story of a fourteen-year-old girl who went to meet her boyfriend for a date. When the boyfriend did not show up, she accepted another man’s invitation to go for a walk. Instead of seeing her safely home, “when it got dark, he assaulted her.” Afterward, “afraid to go home.” she exchanged sex for dinner, a hotel room, and cash before being “nabbed” by the authorities.[7]

Others were tricked into the sex trade. Tarbell recorded the tale of “Clare D.,” a motherless child who “was never properly fed, clothed, or sheltered.” After running away from her abusive stepmother, the homeless teenager accepted the seeming hospitality of some other young women. As it turned out, Clare had unknowingly taken up residence in a brothel, where the madam insisted on payment for room and board and for the “fine clothes” she had accepted as a gift.[8]

Criminality and (Im)morality

Although Bedford inmates engaged in extramarital sex for a variety of reasons—often related to their lack of resources—Davis consistently attributed her charges’ alleged crimes to personal failings rather than to financial pressures. While Davis—whose Ph.D. was in economics—astutely ascribed the demand for the sex trade to the sexual double standard, which assumed a “sex necessity” for men, she refused to acknowledge economic need as an explanation for the supply of sex workers.[9]

Davis noted that women’s wages as domestic servants and factory workers were well below “the minimum on which a girl can live decently in New York City.” Despite the existence of a national movement to establish a minimum wage for working women specifically to prevent them from entering prostitution, however, she attributed women’s participation in the sex trade to immorality rather than to poverty, insisting that “there would seem to be no indication of real economic pressure as a reason for entering an immoral life.”

Davis categorized only 19 of 671 reasons given for entering the sex trade (or less than 3%) as “directly economic reasons.” However, a reexamination of Davis’s data reveals that more than half of the total reasons inmates gave were entering the sex trade were economic. (For instance, Davis classified being “turned out” as a family problem rather than a financial one.) Similarly, Davis believed parole violations resulted from “immorality,” even though the most common offense was leaving a job placement without permission.

“Bad Heredity” and “Moral Imbeciles”

Davis’s focus on morals rather than money increasingly inclined her toward eugenic explanations for criminality and immorality. In the Progressive Era, eugenic ideas about “better breeding” gained traction as a way to improve both individuals and society. Davis initially gave equal weight to heredity and environment, describing them as “hopelessly entangled.” But as she became convinced that both initial sentences and parole violations reflected her charges’ inability to conform to prevailing standards of sexual morality, she looked to the emerging field of eugenics for explanations.[10]

As early as 1906, Davis warned that “bad heredity” was responsible for the problem of what she dubbed “moral imbeciles.” These young women “can not distinguish between right and wrong,” she explained, “so they become a fearful menace to society.” “Moral imbeciles,” Davis warned, “debauched” young men. Moreover, they bore children out of wedlock. Drawing on prevailing eugenic theories, Davis predicted: “If there is anything in heredity,” then “immoral” women’s “illegitimate” children were doomed “to a life of hopeless misery, such as their mothers have suffered before them.”[11]

From “Moral Imbecility” to Mental Defect

Although initially Davis acknowledged that many inmates had “good minds,” she soon linked “moral imbecility” to mental defectiveness. Beginning in 1909, Davis hired a cohort of highly educated women to assist her in testing and classifying inmates. These included Mabel Ruth Fernald, Alberta S. B. Guibord, Virginia P. Robinson, Eleanor Rowland, Edith R. Spaulding, Jessie Taft, and Clara Jean Weidensall. For this pioneering group of female physicians and psychologists, working with Davis offered unprecedented opportunities for professional advancement. As Robinson recalled: “That we brought no qualifications for working with criminal women except interest did not disturb Miss Davis, nor did it disturb us. This was our chance for vital gripping experience, and we plunged into it without a qualm and with no regrets.”

Davis’s staff quickly became conversant with prevailing theories of hereditary traits and the new procedures of intelligence testing. They studied with Henry Goddard, who adapted and popularized French psychologist Alfred Binet’s intelligence tests, Charles B. Davenport, an advocate of selective breeding and founder of the Eugenics Records Office, and William Healey, director of Chicago’s Juvenile Psychopathic Institute.

With the guidance of these prominent eugenicists, Davis and her colleagues undertook a series of studies of Bedford’s residents. Disregarding inmates’ low levels of formal education (approximately half had not completed grammar school), they concluded that a significant proportion of inmates had mental ages of twelve or younger. By 1913, such studies had convinced Davis that “delinquent women” included “a high percentage of mental defectives.”[12]

From Short-Term Rehabilitation to Long-Term Institutionalization

Equating “moral imbecility” with mental incapacity had profound implications. Davis believed that treatment should “fit the criminal,” not “fit the crime.” Initially, this meant that she tailored rehabilitation programs to individual needs and desires. But once Davis defined moral deviance as mental defect, she advocated that certain offenders should be confined for life, rather than serving a set sentence for a specific offense. Since she regarded intelligence as a fixed and inheritable characteristic, Davis asserted that the only “rational” solution to the “social menace” of female immorality was the permanent confinement of “feeble-minded delinquents” in custodial institutions.[13]

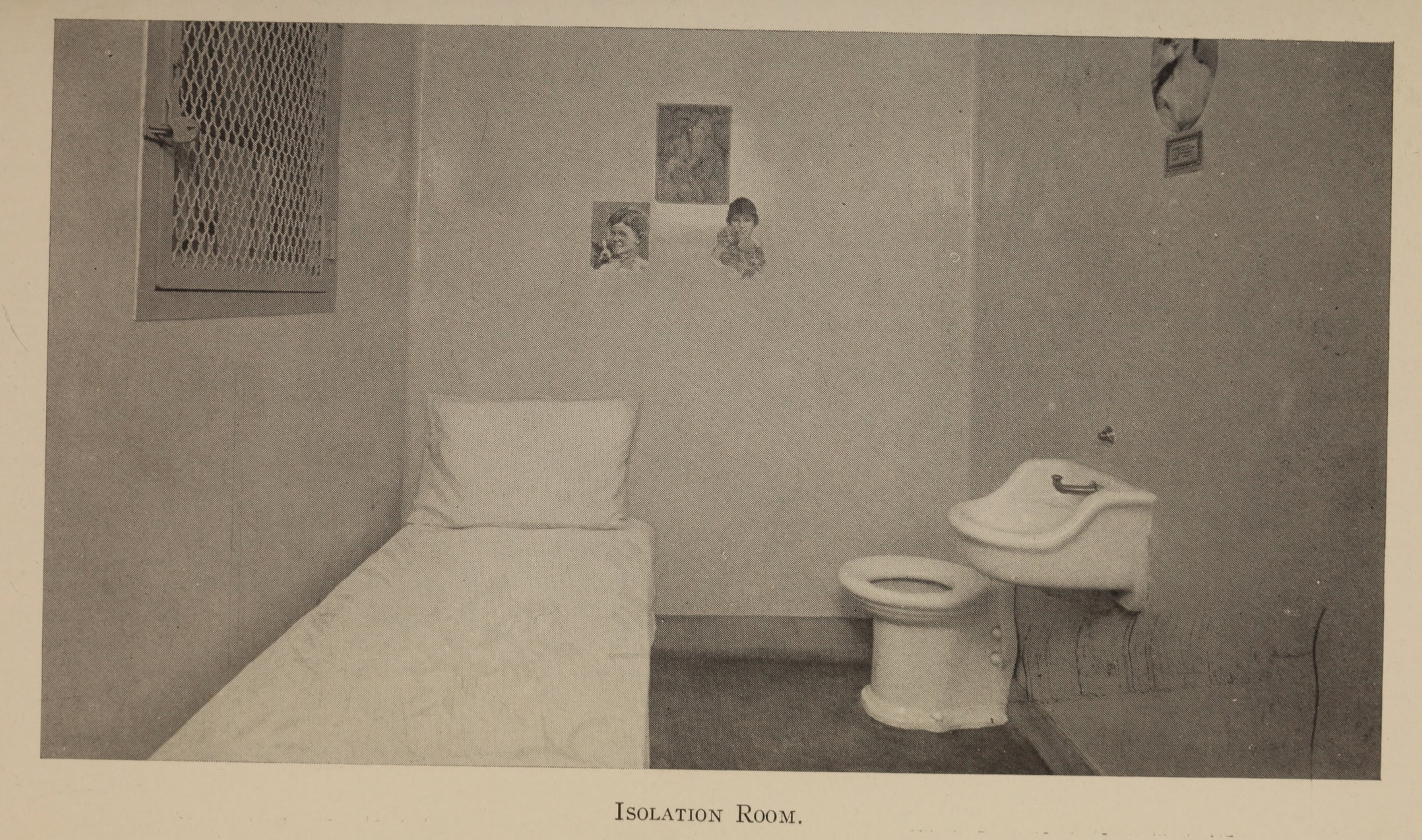

Davis ended her career in corrections before the long-term commitment of “defective delinquents” became a reality. In the meantime, she advocated indeterminate sentences as a way to separate female offenders from the free population—and prevent their reproduction. At Bedford, all inmates served a three-year sentence with the possibility of parole. Ideally, this type of indeterminate sentence encouraged good behavior and led to early release. As Davis explained, “the prisoner should recognize that her only hope of freedom is in preparing herself to lead an industrious, self-supporting life.” But if early release was the carrot, permanent institutionalization was the stick. As Davis put it, “a genuinely indeterminate sentence has as its logical outcome the custodial care of all prisoners whom it is not possible to train to good citizenship.”[14]

“Respectable Women,” Eugenic Sterilization, and the Carceral State

In 1914, Davis left Bedford to become the first female Commissioner of Corrections for New York City, narrowly avoiding implication in a scandal about interracial, same-sex relationships that erupted at the reformatory the following year. After quelling a riot at Blackwell’s Prison, she moved on to a post on the parole board. In 1917, she joined the staff of the Bureau of Social Hygiene, which had funded much of her research at Bedford. After participating in the World War One campaign to combat prostitution and venereal diseaseI, including producing a government-sponsored film intended to discourage extramarital sex, she authored a pathbreaking study, Factors in the Sex Life of Twenty-Two Hundred Women (1929), in which she frankly acknowledged women’s sexual desire and documented women’s sexual activity—both heterosexual and homosexual. The resulting furor led to Davis’s early retirement, suggesting the dangers of publicly advocating a modern moral code. As a sex researcher, Davis was an important advocate for women’s sexual self-expression. But as a penal reformer, she left a more troubling legacy.

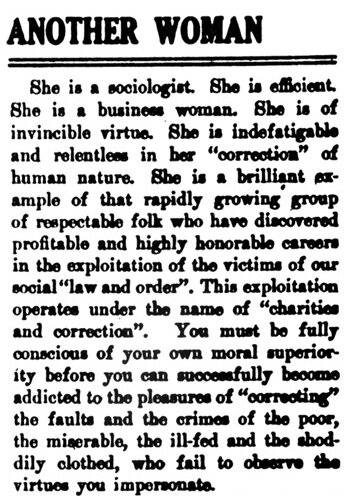

In 1914, birth control advocate Margaret Sanger sharply criticized Davis, calling her “a brilliant example of that rapidly growing group of respectable women who have discovered profitable and highly honorable careers in the exploitation of the victims of our social ‘law and order’ . . . under the name of ‘charities and corrections.’”

Sanger’s critique has merit. The female reformatory movement used assumptions about women’s morality to create new professional opportunities for middle-class, educated, white, native-born women like Davis and her colleagues even as it consigned poor, uneducated, immigrant, and Black women to second-class citizenship. While Davis ended her career in corrections before her dream of confining “defective delinquents” to custodial institutions became a reality, other prison officials and medical professionals incorporated eugenics into policy, leading to the institutionalization and sterilization of thousands of “mental defectives.” Although discredited after revelations of genocide in Nazi Germany during World War Two, eugenic theories have continued to guide US policy, authorizing the medical mistreatment of African Americans, individuals with disabilities, indigenous peoples, and undocumented immigrants—and, most recently, pop star Britney Spears. Ironically, although Davis employed eugenic arguments primarily to explain the behavior of middle-class and native-born offenders—she believed that environment explained the offenses of foreign-born European immigrants and southern-born Black migrants—both the eugenic theories she espoused and the carceral system she promoted disproportionately control and punish poor, immigrant, and nonwhite people.

But exploring Davis’s career does more than expose one individual’s shortcomings. It offers insight into both women’s role in constructing the carceral state and the long-term consequences of women’s participation in the criminal justice system. Many aspects of Davis’s career in corrections—her initial enthusiasm for and her subsequent disillusionment with rehabilitation, her persistent focus on “immorality,” and her eventual turn to eugenics—reflected common trends in Progressive-Era penal reform. Thus, Davis’s career highlights how women’s prominent role in prison reform has contributed to contemporary problems. Although the female reformatory movement began as an attempt to assist unfortunate women, ultimately, women’s participation in the carceral state laid the groundwork for forced sterilization and mass incarceration.

Correction: A previous version of this post referred to Bedford Hills as Bedford Falls.

Dr. Anya Jabour

Anya Jabouris Regents Professor of History at theUniversity of Montana-Missoula, where she teaches U.S. women’s history and directs thepublic history program. The author ofSophonisba Breckinridge: Championing Women’s Activism in Modern America(University of Illinois Press, 2019), she is now working on a biography of Katharine Bement Davis. Follow her on Twitter at @anya_jabour.