By Dr. Jill Frahm

June 1, 2021

On March 18, 1907, an anonymous individual at the Fort Dodge, Iowa, city council meeting proposed an ordinance to tax all bachelors and spinsters residing in the town. The proposal, smuggled into a pile of legitimate business papers, required “all able bodied persons between the ages of 25 and 45 years, whose mental and physical propensities and capabilities are normal” to pay a tax of between 10 and 100 dollars: the longer they remained single, the more they would have to pay.[1] The ordinance was recognized as a joke and referred to the sewer committee. However, someone released to the press that the ordinance had passed and single people living in the city were now required to marry or pay the tax. Over the next two weeks, national attention focused on Fort Dodge as papers across the country debated the merits of such a law.

I first ran across this story several years ago when I was working on my dissertation. At first, I thought a bachelor tax was nothing more than a joke as it was in Fort Dodge–a bit of Progressive Era humor that I failed to completely appreciate. Yet, reports of a bachelor tax were taken seriously across the country. As I dug deeper into the topic, I discovered that several states and towns seriously considered such a measure. While some people saw a bachelor tax as a ridiculous idea, others saw it as a way to solve a serious problem they perceived as plaguing the country at the time–“race suicide.”

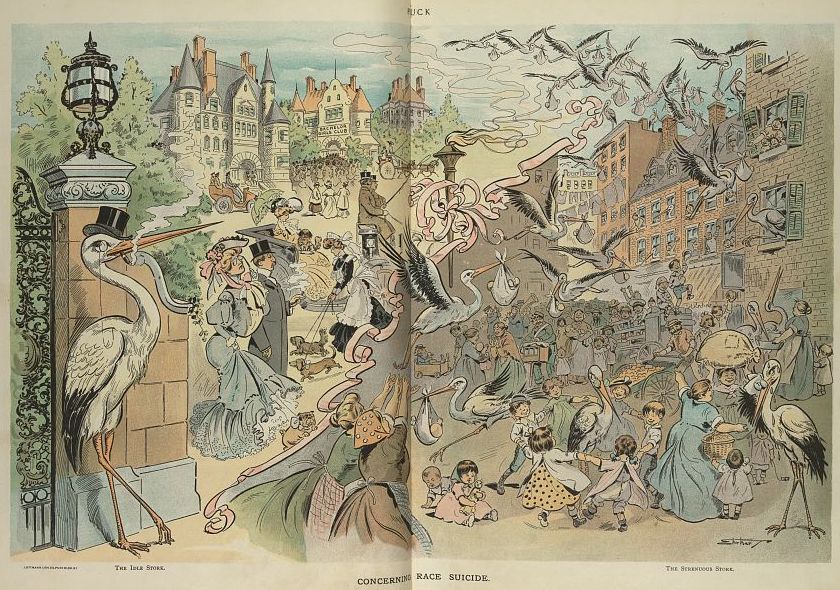

The years following the Civil War saw an increase in immigration to America, which sparked a nativist backlash that intensified by the 1890s. Commentators as early as 1867 “warned that large families of foreigners would overwhelm Anglo-Saxon stock,” leading to race suicide.[2] These fears only increased when a shift in immigration brought large numbers of “new” immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe to the United States by the early 20th century. As nativists urged native born white men and women to wed young and have many children, they also recognized that there were increasing numbers of white, U.S.-born men and women remaining single their entire lives. This tendency toward life-long singleness was adding to what the nativists already perceived as a very serious national problem. Nativists wanted an immediate solution.

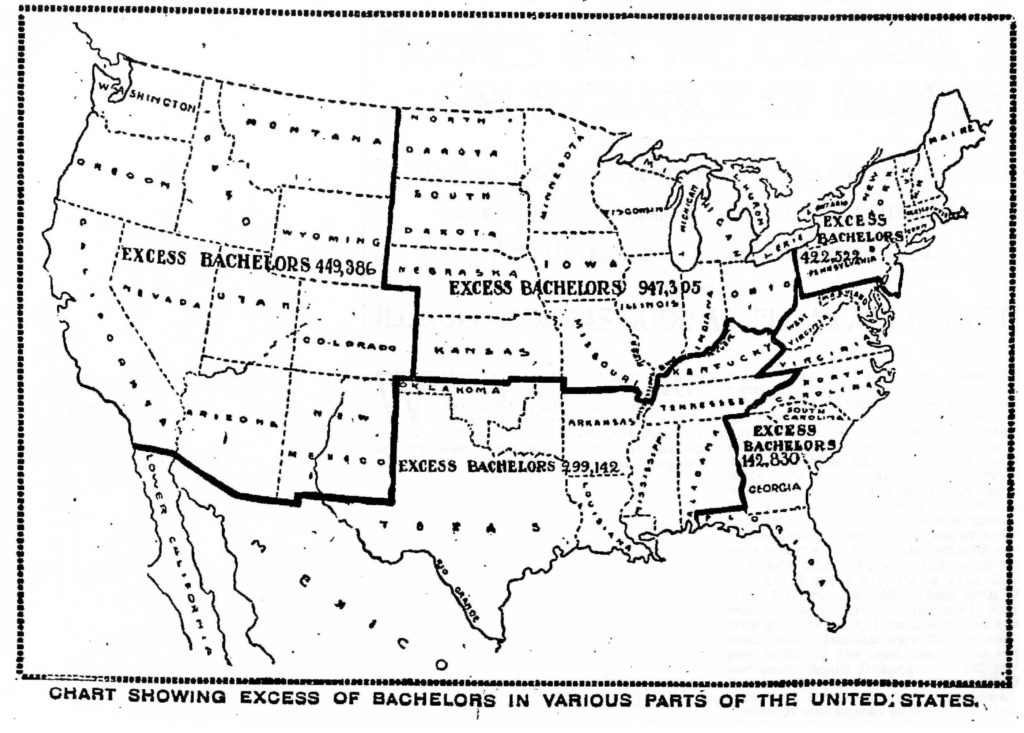

Between 1880 and 1930, newspapers all over the United States carried a variety of articles related to why men and women did not marry and how the problem might be solved. The issue of why women remained single, for example, was considered by the editor of The Independent as one of the most important of his time—one which “the future of civilized races depends upon.” “If the spiritually gifted become priests and nuns and the intellectually gifted become celibate professors…” he continued, “there is no conceivable way by which the loss to humanity can be repaired in future generations.”[3] Many ideas were floated on how to reverse this trend. For example, in 1898, the U.S. Census Bureau published what the popular press dubbed an “Old Maids Chart” (figure 2), graphically illustrating “at a glance in what localities bachelors [were] the thickest, and in what regions spinsters [were] most dense per square mile.”[4] With such a chart in hand, single men and women could relocate to the region where their chances of marriage would be the greatest. The town of Panhandle, Texas advertised for “100 single women…to come to Panhandle and marry our thrifty young men.”[5] In 1908, the Salt Lake Herald and the Washington Times both urged the District of Columbia’s supposedly large surplus of women to go elsewhere to find a mate.[6] Authorities like Presidents Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft wrote articles celebrating marriage and family life. Articles like “Wed and Live Long, Says Dr. Bertillion” appeared in the January 23, 1910 issue of the New York Times and presented statistics to “prove” that if a person married, their life expectancy would increase. If this was not enough, individuals like psychologist and educator G. Stanley Hall began to “[advocate] legislation to force ‘selfish’ native-born bachelors to marry.”[7] The bachelor tax was just one part of nativist efforts to combat the suicide of the Anglo-Saxon race.

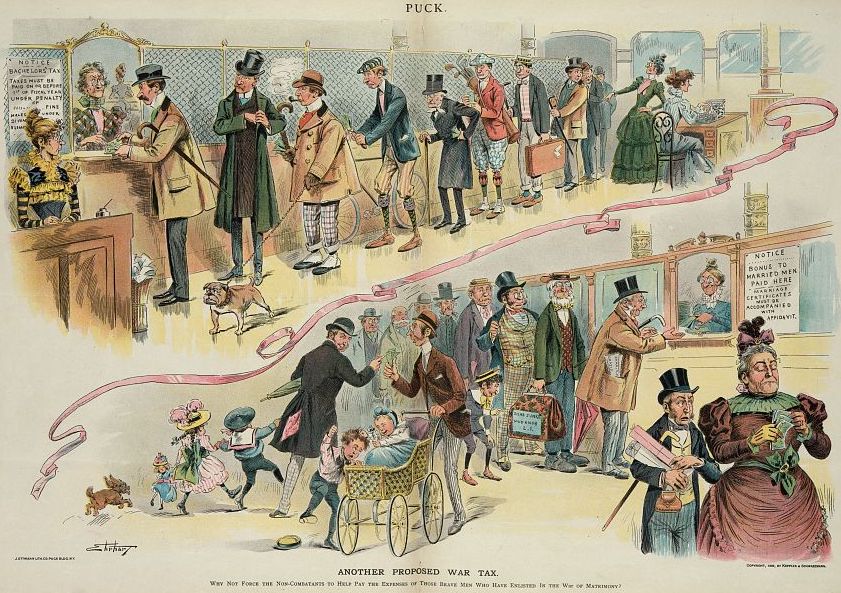

A bachelor tax is exactly what it seems: a tax paid by men, and sometimes women, who reached a certain age without ever marrying. As laws pertaining to marriage were outside the responsibility of the federal government, bachelor tax proposals only ever appeared at state and local levels. The tax might come in one of several different forms: a flat tax, as proposed in Fort Dodge, a poll tax[8], or a higher rate on a marriage license for people over a certain age. The latter, however, was denounced as a deterrent to marriage rather than an incentive. For example, a columnist in the Adair Country News of Columbia, Kentucky, wondered, “Just what object the legislators propose by allowing the men of Connecticut to roam around in hardened bachelorhood untaxed and yet threatening to fine them if they marry after forty is not apparent.”[9] However gained, the resulting revenue was typically designated to support some group of people who were thought to be destitute because the bachelors were not performing their duty—orphans, aged spinsters, or widows.

Bachelor taxes were extremely controversial and their consideration in any state resulted in a flurry in the local and national press. The Minneapolis Tribune endorsed Wyoming’s efforts to pass such a tax in 1890: “the Tribune favors the taxation of bachelors and would gladly welcome such a law in Minnesota.”[10] Poet Ella Wheeler Wilcox similarly supported the idea and claimed, “Since it is man’s prerogative to decide the question of his own and of some woman’s life in this important matter, he who elects to be a bachelor ought to be ready to pay a tax toward the support of single women.”[11] However, for every commentator in favor of bachelor taxes, at least one pronounced against them. The Bourbon News of Paris, Kentucky described Indiana’s proposed bachelor taxes as “freak” legislation.[12] A letter to the editor of the New York Evening World claimed such taxes were a “personal insult to mankind and womankind in this twentieth century of enlightenment in this freest country of the universe.”[13] The reports of the passage of the law in Fort Dodge resulted in national comment ranging from praise to an editorial that described Fort Dodge mayor Bennett, the suspected father of the law, as “the nuttiest freak outside a padded cell.”[14]

Determining how many places around the country actually passed a bachelor tax is complicated. Stories of proposed bachelor taxes from places as diverse as New Jersey, Illinois and Wyoming appeared in newspapers between the 1880s and 1920s. However, most of these taxes were later dismissed as a hoax or defeated in the state legislature. To this point Montana is the only state that clearly had bachelor tax for any length of time.

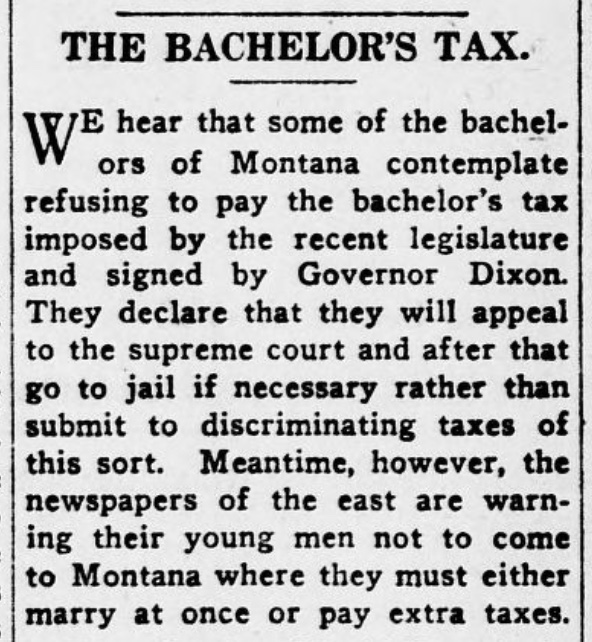

On March 16, 1921, Montana governor Joseph M. Dixon signed a bachelor tax into law. This placed a $3 poll tax on all “male persons in Montana between the ages of 21 and 60 who [were] not the heads of families.”[15] The money raised was to go to a “widow’s fund,” apparently to help those women who would not need support had the bachelors done their duty by marrying them. While there were some efforts to defeat the bill, the Montana newspapers covering its progress through the legislature did not indicate any strong objection to it. The measure passed both houses by comfortable margins. Some bachelors submitted to the tax with humor. Alfred Pryor declared that “the state would receive his contribution indefinitely and welcome.”[16] R. G. Linebarger, proudly the first man in Havre, Montana, to pay the tax, “boasted of being the foremost bachelor in the community. He [showed] his tax receipt to all the girls.”[17] Other bachelors were less sanguine about the prospect of paying the tax. According to the Great Falls Tribune, some unnamed bachelors declared “that they will appeal to the supreme court and after that go to jail if necessary rather than submit to discriminating taxes of this sort.”[18] Within three weeks, such men “commenced looking to the annulment, by legal proceedings, of the tax on bachelors.”[19] The law did not stand up to their challenge in court. Montana’s bachelor tax was only in place for about 10 months when it was declared unconstitutional in January 1922. The state then spent the next several months refunding the tax money the bachelors had paid.

Discussion of imposing bachelor taxes in the United States died off after the Montana law was struck down. It was clear that a bachelor tax would not stand up in court. At the same time, the rate of lifelong singleness in the United States began to decline in the 1920s, even as new immigration restrictions significantly limited the number of people coming to America. The perceived urgency for such legislation disappeared.

Did bachelor taxes have any effect on marriage in the United States? Probably not. Life-long singleness was already in decline when the Montana law was passed and immigration restrictions went into effect shortly thereafter. Even if it had been effective, Montana’s population of bachelors and spinsters was too small to make a significant difference nationally and I have not been able to identify any other place where a similar law was enacted. However, the mere discussion of such a law illustrates how concerned Progressive Era nativists were about the suicide of the Anglo-Saxon race. By passing laws to force people to marry, they could set the stage for population recovery. Ironically, by the 1930s, newspapers across the country were poking fun at what their editors saw as foolish and unusual legislation coming from places outside the United States: bachelor taxes.

Dr. Jill Frahm

Jill Frahm received her PhD in U.S. History from the University of Minnesota. Her research and writing focus on unconventional women of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era. She teaches history at Dakota County Technical College in Rosemount, MN.