By Nicholas L. Syrett

October 9, 2024

This is a continuation of the forum on the history and legacy of Anthony Comstock. This forum is forthcoming in the Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era and is formally titled The History and Legacy of Anthony Comstock and the Comstock Laws. Given our current debates on abortion following the Dobbs decision and the Heritage Foundation’s Project 2025, which proposes to revive the Comstock Act, we hope this forum will provide useful historical context about the Act’s influence on American life. This is the sixth of seven installments. All posts will be available here as they are published.

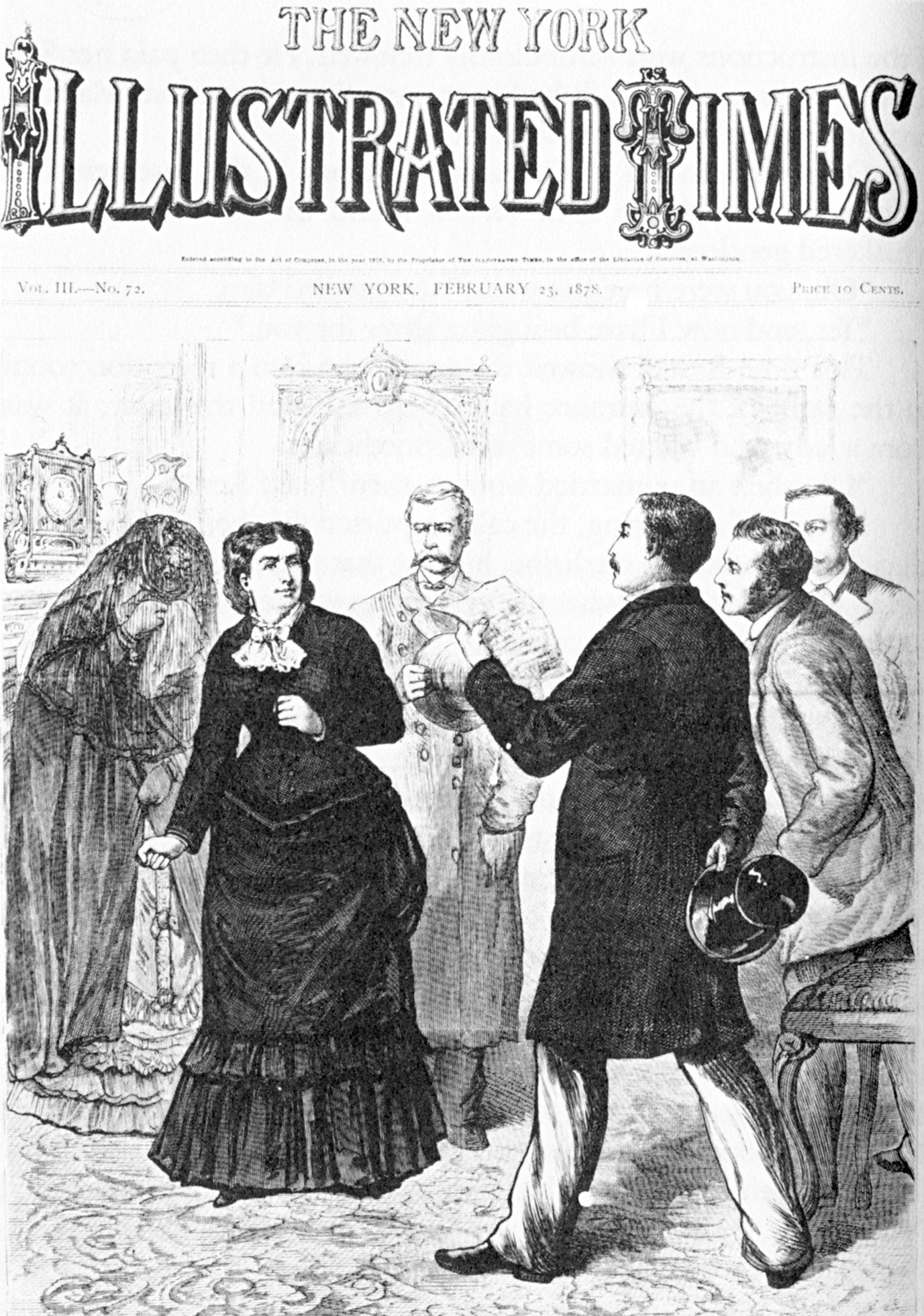

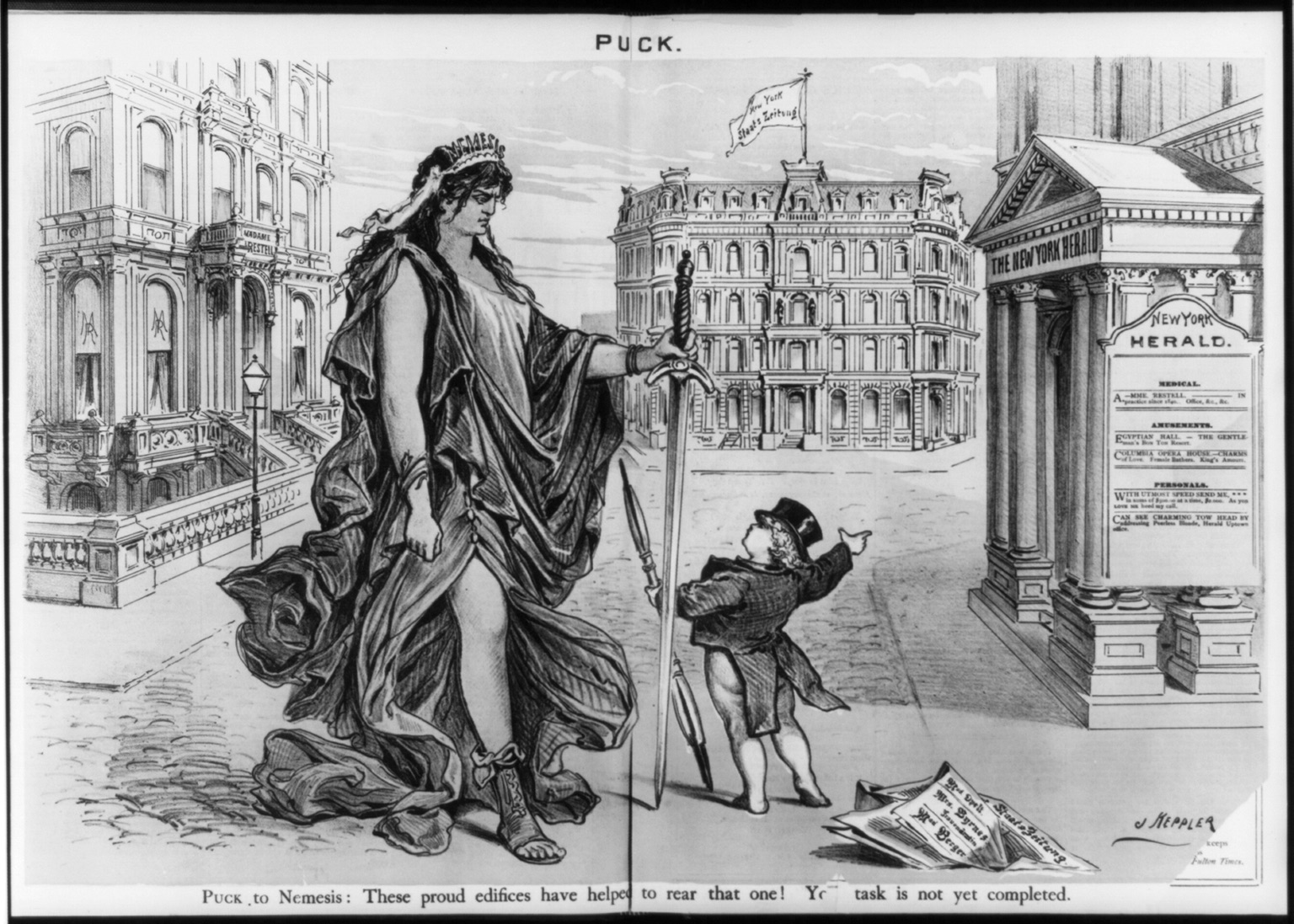

Anthony Comstock arrested many people, but perhaps none was so famous as Madame Restell, whom he arrested on February 11, 1878, for selling contraceptives and abortifacients. While Comstock’s actions had led to the arrest of other celebrated personae in the past—including Victoria Woodhull, her second husband James Blood, and her sister, Tennessee Claflin in 1872—Restell’s arrest and looming trial led her to commit suicide by slitting her throat on April 1, 1878, which leant even further notoriety to the arrest.[1] Because Restell remains best known as an abortion provider, and because Comstock succeeded in passing a federal statute that bears his name, one might assume that abortion occupied a central place in his campaign, or that Restell was arrested for performing an abortion. Neither is completely accurate. Indeed, Restell was not even arrested under the aegis of the federal statute, but instead under New York State law, though certainly at the instigation of Comstock and by him personally. By taking the arrest of Restell as a case study, this post considers the various legal modes by which Comstock did his work, and the way he understood abortion as related to his greater campaign against obscenity and sexual license.

Madame Restell was the pseudonym of Ann Trow Summers Lohman (1811–1878), the most famous abortion provider in nineteenth-century America (Figure 1). Lohman was an English immigrant who came to New York with her first husband and daughter in 1830 or 1831 and went into business as what she called a “female physician” in 1839, running an increasingly successful practice until her death in 1878. She became fantastically wealthy and she and her second husband, Charles Lohman, built a sizable mansion at the corner of Fifth Avenue and 52nd Street with the profits from her own and her husband’s business selling contraception and abortifacients.

Ann Lohman called herself a female physician because she did what midwives had been doing for hundreds of years in the United States and its earlier colonies: she delivered babies in a lying-in hospital that was part of her home; she terminated pregnancies manually and via abortifacient; she sold contraception and emmenagogues; and she sometimes helped women arrange for the adoption of infants born there. While Lohman did see married as well as single women, in much of the coverage of her work, the press assumed her clients were single women giving birth to bastard children or terminating illegitimate pregnancies. It was also the case that married women had other options for giving birth, either by hiring doctors or midwives to attend to them in their own homes, if they had the funds, or by staying at the New York Asylum for Lying-In Women, which only accepted married women as patients. Many thus indicted Lohman as being an accomplice to licentiousness in that she aided those who had sinned by having sex out of wedlock. Some critics also condemned her as aiding wealthy rakes and libertines by covering over the sin of illegitimacy.[2]

It is worth noting that one of the things that made Madame Restell unique among her competitors – and also made her a target for doctors, moralists, and vice crusaders – was her proto-feminist defense of a woman’s right to bodily autonomy. Although she did not employ phrases like “bodily autonomy,” she explicitly defended a woman’s right to avoid childbirth as being in the interests of her own health and the survival of the family economy. In one of her earliest advertisements, she asked, “Are we not bound by every obligation, human and divine, by our duty to ourselves, to our husbands, and more especially to our children, to preserve, to guard, to protect our health, nay our life, that we may rear and watch over those to whom we are allied by ties the most sacred and binding?” While she cagily couched women’s desire for wellbeing as being in service to their families, Restell also took it as axiomatic that women had a greater stake in reproductive decisions than did men, including women’s own husbands. Her advertisements were frank explorations of what she took to be the obvious logic behind contraception and abortion.[3]

Police arrested Madame Restell a number of times, and she was tried and convicted twice, in 1841 and 1847. While the first conviction was overturned on appeal on a legal technicality, she served a year on Blackwell’s Island for the second conviction on a misdemeanor for terminating a not-yet-quick fetus. Quickening is the moment that a woman can sense fetal movement, which usually occurs around the fourth or fifth month. Like many states, New York state law made a distinction between pregnancies that had and had not quickened; had she terminated a quickened pregnancy, she could have been found guilty of second-degree manslaughter and spent considerably longer in a state prison.

It is difficult to overstate the level of Madame Restell’s fame. She was featured in newspapers across the country and advertised her wares up and down the Eastern Seaboard. Newspapermen published transcripts of her trials and sold them on the city streets. Newspapers also reported on the most mundane aspects of her life, one noting that Restell and her husband did not seem to have any friends, a story that was reprinted as far away as West Virginia and Wisconsin.[4] As the face of criminal abortion in the United States, it is thus curious that Anthony Comstock did not arrest Madame Restell until 1878, despite the fact that he had been active in policing vice since his arrival in New York in 1867, and that Restell was already quite famous at the time.

Comstock himself explained part of the lag in writing to his supervisor at the U.S. Post Office that he had been unable to arrest her earlier “for sending her vile article through the mails” because he could not make a “strong case” and “did not deem it wise, to move until I secured such a case.”[5] Because the Comstock Act specifically policed the use of the mails for transport of anything deemed obscene, he instead pursued her using New York state statutes that criminalized the selling of abortifacients. Comstock visited Restell on two occasions prior to her arrest, purchasing an abortifacient from her the first time and a contraceptive douche from her the second. On both occasions he claimed he was making purchases for an unmarried woman with whom he implied he was having sex. It was on the basis of these sales that he arrested her, carting off “10 doz[en] Condoms, 15 bot[tles] for abortion, 3 syringes, 2 q[uar]ts pills for abortion or about 100 boxes, 250 circulars, [and] 500 powders for preventing conception.”[6]

Comstock arrested Madame Restell not under the Comstock Act, but rather under a New York law that preceded the federal law by some years and that specifically related to the sale – not the mailing – of abortifacients.[7] This persecution was not at all unusual for Comstock. While the Comstock Act itself remains his most lasting legacy, Comstock had been pursuing vice as something of an extracurricular hobby long before he had any official role as an agent of the U.S. Postal Service and before passage of the act bearing his name. Almost from his arrival in New York City he had taken it upon himself to root out obscenity and then call in the police, who largely acquiesced in aiding him in his crusade, especially after he united with the Young Men’s Christian Association, which was also active in pursuing obscenity. Following the passage of the Comstock Act and the founding of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice (NYSSV), Comstock and his allies convinced New York state legislators to allow NYSSV agents to deputize any local police forces to work on their behalf. In the case of Restell, and despite the fact that she did a steady business in mail order contraceptives and abortifacients, Comstock seemed unable to nab her through the mails, so he relied on the New York City police force to arrest her under New York State laws criminalizing abortifacients.[8]

The target of most of his investigations, while certainly focused on obscenity of various sorts, was more wide-ranging than many have realized, since “the Comstock Act” has become so bound up in matters of pornography, contraception, and abortion. In his 1880 compendium, Frauds Exposed; Or, How the People are Deceived and Robbed, and Youth Corrupted, Comstock included chapters on lotteries, bogus mining companies, quacks, sawdust swindlers, watch and jewelry swindlers, bankers and brokers, as well as the subjects that we now associate with him: obscenity, contraception, and the like.[9] It is true that “mailing obscene books” ranked among the most frequent entries in the early years of Comstock’s meticulous tally of his arrests, but it was hardly the only crime he pursued. Even before formation of the NYSSV, the YMCA committee with which Comstock collaborated reported that he had worked to collect 134,000 pounds of books, 194,000 photographs, 60,300 rubber articles, and many more letters, circulars, and other articles.[10] In those early years, the vast majority of those arrested were men, which is not surprising, given that men would have been more likely and able to be in the business of manufacturing and selling anything, including articles Comstock deemed obscene. He also arrested people on more petty crimes. In 1876, he arrested William Van Wagner for “indecently exposing himself entirely nude at window for an hour at a time.” The year before he had led police to arrest Jane Beebe for “giving away pictures of her own nude person, to young men, on the street.” In 1875, he arrested Sarah Sawyer in Boston for “mailing obscene circulars, of articles for abortion, prevention of contraception, + indecent + immoral use.” He described Sawyer as “the Restell of Boston,” and it is noteworthy that in his description of this arrest, as in that of Restell, abortion was not seen as somehow worse or more criminal than obscenity or articles to be used to prevent pregnancy.[11]

Comstock’s views on abortion were very much of a piece with his views about sex. What made abortion wrong in his eyes was not that life began at conception or that abortion was “infanticide,” although some doctors at the time did claim those reasons for their own opposition to the practice. What most irked Comstock about abortion was that it provided a way for men and women alike to avoid the consequences of sex. While Comstock shared with many of his contemporaries a hostility to sexually active unmarried women, he also opposed male licentiousness. Like many of his contemporaries, what most concerned Comstock were young people who were not married. If the consequences of sex, in the form of pregnancy, could be avoided, then what was to restrain single young people from sex outside of marriage? He was also particularly concerned that abortion was a way for older men to take advantage of single women. In one 1872 case where Comstock sought to arrest a man named George Selden for selling obscene materials, he caught Selden performing an abortion on a seventeen-year-old girl named Barbara Voss, who had been impregnated by her employer, who was fifty-five. The case left a lasting impression. Comstock believed that banning abortifacients would, in theory, prevent men from taking advantage of women.[12]

Comstock’s concerns about married women and abortion, which he shared with many others, were twofold. He believed that abortion could allow for the concealment of infidelity. In giving testimony about Restell, Comstock reported that during his first visit to her, another client had also been visiting Restell. He claimed that Restell explained, “Poor little dear; her husband has been away for some two months and she has been indiscreet and got caught, and has come for relief.” Comstock reported that Restell said she regularly treated women who wanted to avoid getting caught, exactly what Comstock believed should happen to them. Even if pregnancy were the result of marital sex, women who terminated their pregnancies were turning their backs on the role that men like Comstock believed was natural, as ordained by God: motherhood. In writing about his third and final visit to Restell, he explained that “at time of arrest, a prominent man’s wife, a mother of 4 children was there to consult this woman professionally. She was very greatly excited and pleaded I would not expose her, saying ‘she would kill herself first.’ I told her to sin no more, your secret shall be kept sacredly by me.” We do not know whether the woman was seeking contraception or an abortifacient, but for Comstock it did not much matter; the sin was that she was attempting to avoid what he saw as the destiny of a married woman.[13]

Why does all of this matter? It helps us to understand that Comstock was much more than the act that bears his name. He had been operating for years prior to 1873 and called upon a variety of laws, including those that pre-dated and post-dated the Comstock Act of 1873, in order to police obscenity as well as crimes wholly unrelated to sex like gambling, lotteries, and various forms of swindling. More importantly, understanding Comstock’s opposition to abortion helps to differentiate it from contemporary objections to the practice that center on the potential life of the fetus. Instead Comstock objected to abortion for the same reason he objected to dirty pictures: because he believed that all sex belonged within marriage, where its participants should legitimately welcome its consequences.

A focus on Comstock’s interactions with Restell and the issue of abortion also highlights divergent attitudes toward the practice. Restell was always frank in her estimation that women had a greater stake in the question of reproductive autonomy than did men. She was a “female physician” because she was a woman who saw to the unique medical needs of women, most of which had to do with reproduction. While Comstock opposed the double standard, he was also unable to see how women were uniquely disadvantaged by an inability to control their reproductive destinies. In this way, he was not unlike the justices who decided Dobbs v. Jackson.

[1] On Woodhull, Blood, and Claflin, see Debby Applegate, The Most Famous Man in America: The Biography of Henry Ward Beecher (New York: Crown, 2007), 422. Ida Craddock also took her own life in 1902 after having been arrested by Comstock for selling obscene materials and subsequently tried and convicted. See Shirley J. Burton, “Obscene, Lewd, and Lascivious: Ida Craddock and the Criminally Obscene Women of Chicago, 1873–1913,” Michigan Historical Review 19 (Spring 1993): 1–16.

[2] Parts of this piece are drawn from Nicholas L. Syrett, The Trials of Madame Restell: Nineteenth-Century America’s Most Infamous Female Physician and the Campaign to Make Abortion a Crime (New York: New Press, 2023).

[3] “To Married Women,” New York Morning Herald, Nov. 2, 1839.

[4] “Madame Restell and Her Husband,” printed in Wheeling (West Virginia) Daily Intelligence, Aug. 28, 1856, and Weekly Wisconsin (Milwaukee), Oct. 15, 1856.

[5] Anthony Comstock to David R. Parker, Feb. 13, 1878, Ann Lohman folder, box 23, RG 28, Postal Inspection Service, 1832–1970, Records of the Post Office Department, National Archives, Washington, DC.

[6] Entry for Feb. 11, 1878, volume 1, page 111, New York Society for the Suppression of Vice Records, 1871–1953, Library of Congress (hereafter NYSSV Records).

[7] New York first passed a statute on abortion in 1829 and revised it multiple times in subsequent years. For the first statute, see Revised Statutes of the State of New York (Albany, NY: Packard and Van Benthuysen, 1829), 2:661, 663.

[8] Amy Werbel, Lust on Trial: Censorship and the Rise of American Obscenity in the Age of Anthony Comstock (New York Columbia University Press, 2018), 51–95.

[9] Anthony Comstock, Frauds Exposed; Or, How the People are Deceived and Robbed, and Youth Corrupted (1880; Montclair, NJ: Patterson Smith, 1969).

[10] Werbel, Lust on Trial, 52.

[11] Van Wagner was arrested on January 17, 1876, and Beebe in December 1875; NYSSV Records.

[12] Werbel, Lust on Trial, 68–69.

[13] Testimony of Anthony Comstock, The People on the Complaint of Anthony Comstock v. Ann Lohman, Feb. 23, 1878, 5–7; Testimony of Anthony Comstock and Charles O. Sheldon in The People on the Complaint of Anthony Comstock, Feb. 23, 1878, 13–14, both in Comstock Folder, Madame Restell Papers, Schlesinger Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts.