By Janet Olson, Archivist, and Kristin Jacobsen, Assistant Archivist, Frances Willard House Museum and WCTU Archives, Evanston, IL

September 29, 2020

This post is part of a series exploring the lived experience of Americans during the 1918 flu pandemic. Read the other posts in the series here.

The 1918 influenza pandemic provides an opportunity for GAPE historians to examine how health and medicine intersected with the Great War, the Progressive Era, and the movements for prohibition and woman suffrage.[1] The Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) was at the confluence of these streams and offers a case study of an organization whose activities were disrupted and reshaped by the pandemic. The holdings of the WCTU Archives reveal how the national organization mobilized the testimony of health experts and “viral” newspaper reports in 1918 to support its Prohibition ratification campaign and resist attempts by the producers and suppliers of alcohol to push their products as an influenza cure.

Since its founding in 1874, the WCTU had maintained the prohibition of alcohol production and consumption as its primary goal but had broadened its platform to include woman suffrage, economic equity, fair labor laws, pure food, and other reforms to counter the social causes of alcoholism. In 1918 it was still one of the largest women’s organizations in the United States, and it also had a strong international presence. At the time of the influenza pandemic, the WCTU had three major concerns: war recovery, the ratification of the Prohibition amendment (passed in December 1917), and the passage of the suffrage amendment. The pandemic forced the WCTU to reprioritize its work. While the organization cancelled local and national meetings and lost members to the illness, the biggest threat posed by the epidemic was its critical timing in the midst of the Prohibition ratification campaign. Not only did the disease distract the public’s attention from the campaign, but articles claiming that alcohol cured influenza posed a serious threat to ratification. And it was obvious to the WCTU that much of the false information about the curative power of alcohol was propaganda disseminated by alcohol producers and suppliers.

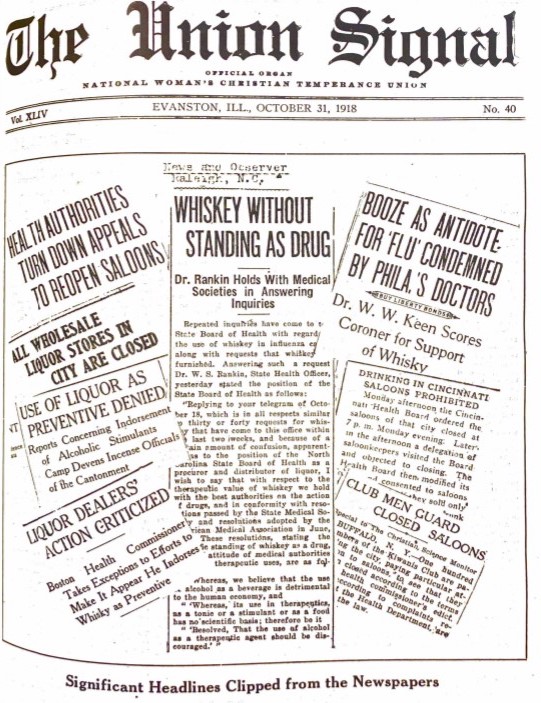

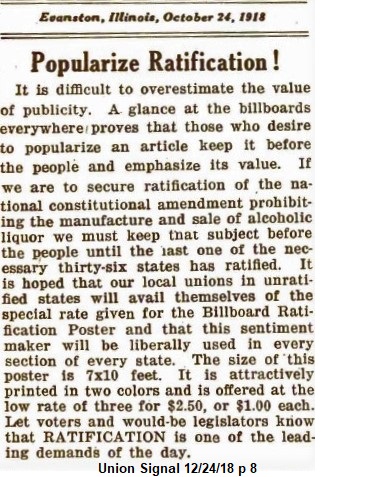

To counteract what it saw as the alcohol industry’s propaganda, and to keep the 18th Amendment on track, the WCTU mobilized its most effective weapon of communication: the Union Signal, the organization’s national, weekly newspaper with nearly 25,000 subscribers.[2] In the fall of 1918, when 15 states had ratified Prohibition out of the 36 needed to pass, the Union Signal published 25 articles and covers on the influenza epidemic—all but five related specifically to alcohol. The October 31, 1918, issue alone, with its dramatic cover, accounted for 10 articles.

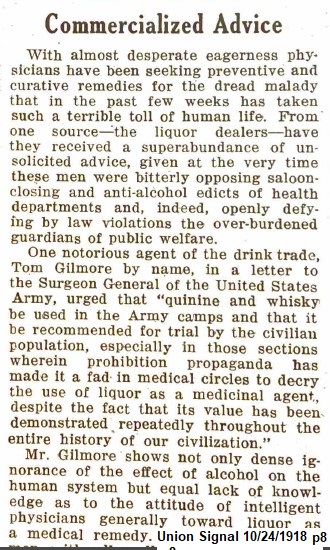

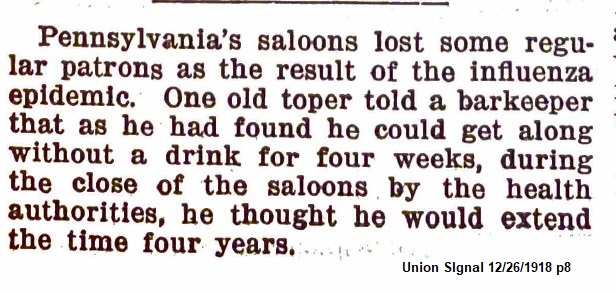

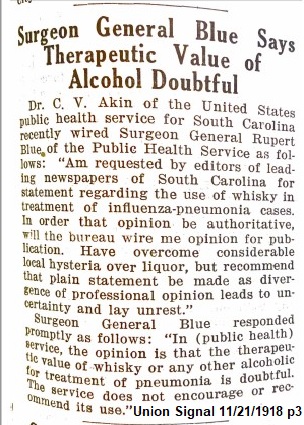

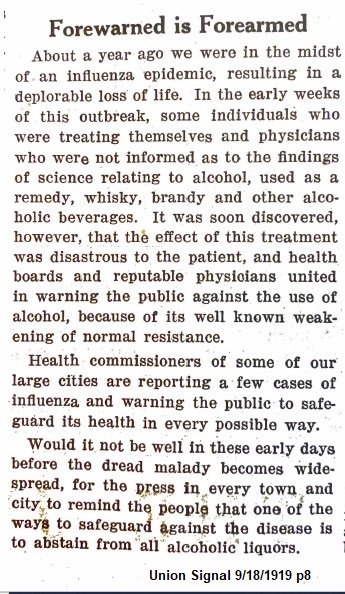

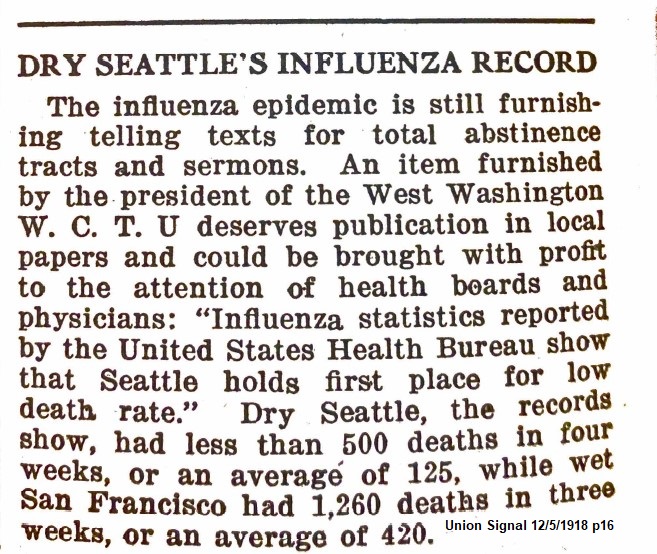

For the next few months, in articles based on reports from around the country, the editors of the Union Signal took several approaches to refute the idea of alcohol as an influenza remedy. Reflecting the era’s confidence in expert advice, the WCTU quoted public health officers, doctors, and military officials on the inefficacy of liquor as a cure (“Boston’s Health Commissioner Refuses Offer of Free Alcohol for Influenza Patients”[3]). The paper called out the liquor industry for appropriating medical authority to sell more liquor (“‘Whisky’ Conducted a Paid Propaganda Campaign during Epidemic”[4]). It pointed to the superior health conditions in dry states and towns and the benefit of closed saloons as examples of life after full ratification of Prohibition (“Minneapolis and St. Paul Sample Prohibition during ‘Flu’ Epidemic”[5]). And it reported on sound practices in military hospitals and camps (“Authorities at Camp Buell and Camp Taylor [KY] Say Practically No Alcohol Was Used for Influenza: Kentucky’s State President in Open Letter, Gives the Facts”[6]).

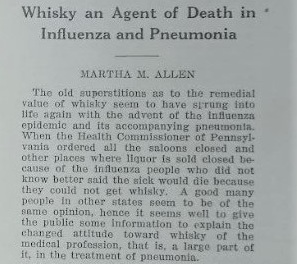

An interest in health issues was not new to the WCTU. Recognizing the negative physical, as well as moral, effects of alcohol, the WCTU had included health and hygiene in its platform since the 1880s.[7] A national Department of Non-Alcoholic Medicine, later renamed Department of Medical Temperance, was formed in 1898 to campaign against alcohol in prescriptions and patent medicines and was closely involved in the campaign for the 1906 Pure Food and Drug Act.[8] The 1918 epidemic gave new urgency to the WCTU’s history of involvement with public health. At the National WCTU annual meeting in 1919, the director of the Medical Temperance Department reported:

The influenza epidemic gave great opportunity to educate against alcohol. … The W.C.T.U. worked faithfully in getting the truth before the people by publishing in local papers the matter from the leaflet, “Whiskey, an Agent of Death in Influenza and Pneumonia.” Tens of thousands of this leaflet were circulated.[9]

The Medical Temperance director’s statement reflects the extent to which the WCTU saw the influenza epidemic as a battleground for the success of Prohibition. It is surprising that the WCTU at the national level did not report more on the suffering of influenza victims and other effects of this national emergency. Further research may show more attention to these aspects at the local or state level of WCTU activism. Yet the WCTU’s response, illustrated by the flurry of articles in the Union Signal, shows how a disruptive element can be assimilated into the social context of an era. The 1918 influenza epidemic’s impact on the campaign for Prohibition suggests parallels to the effect of the 2020 pandemic on our own moment in time. The interruption of ongoing political and reform campaigns; the scramble to reconfigure communication channels; the conflicting information from many sources—medical and scientific as well as hearsay or purposeful disinformation—are obstacles that we see today.

But despite restrictions on its usual arsenal of meetings and parades to educate the public, and ambushed by the alcohol industry’s misleading claims for an influenza cure, the WCTU mobilized the voice of authority and the power of the press among its own constituents to advance the effort to get the Prohibition amendment ratified.

For more information about the holdings of the WCTU Archives, see http://franceswillardhouse.org/research or contact archives@franceswillardhouse.org.

The WCTU Archives has identified 33 influenza-related articles and covers that appeared in the Union Signal between 1918 and 1920, based on the index to the newspaper in the Archives. Those interested in this information are welcome to contact the Archives.