By Dr. Daniel Gifford

February 9, 2021

Discovering Microhistory

Although it was many years ago, I still vividly remember microhistory week in my graduate research and methods course. When employing microhistory, the historian uses a small event or story to illuminate much larger contexts and historical trends. And, as Duane Corpis suggests, one of microhistory’s great strengths is the ability to present “especially peculiar moments in the past” along with “strange and bizarre events.” [1]

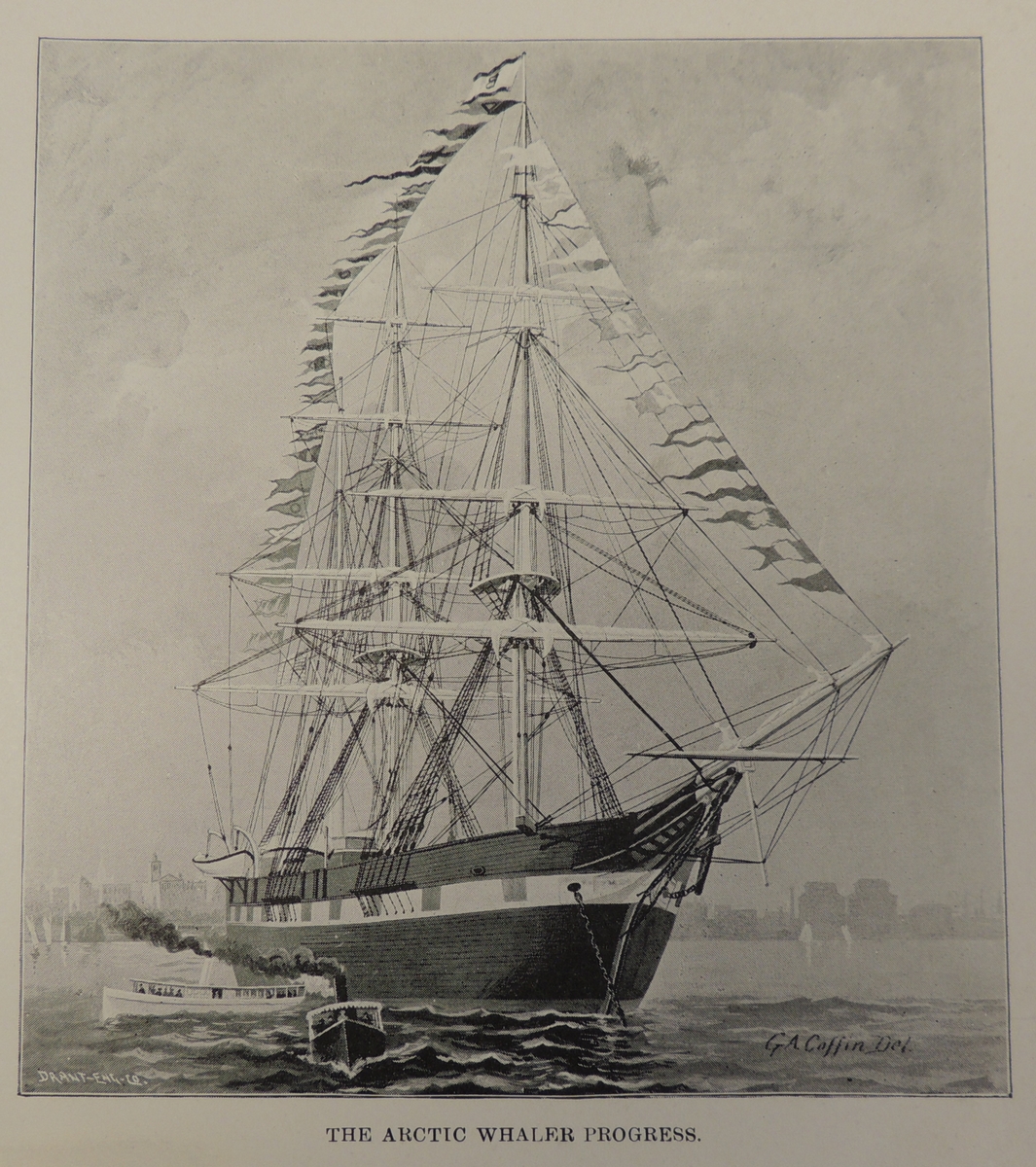

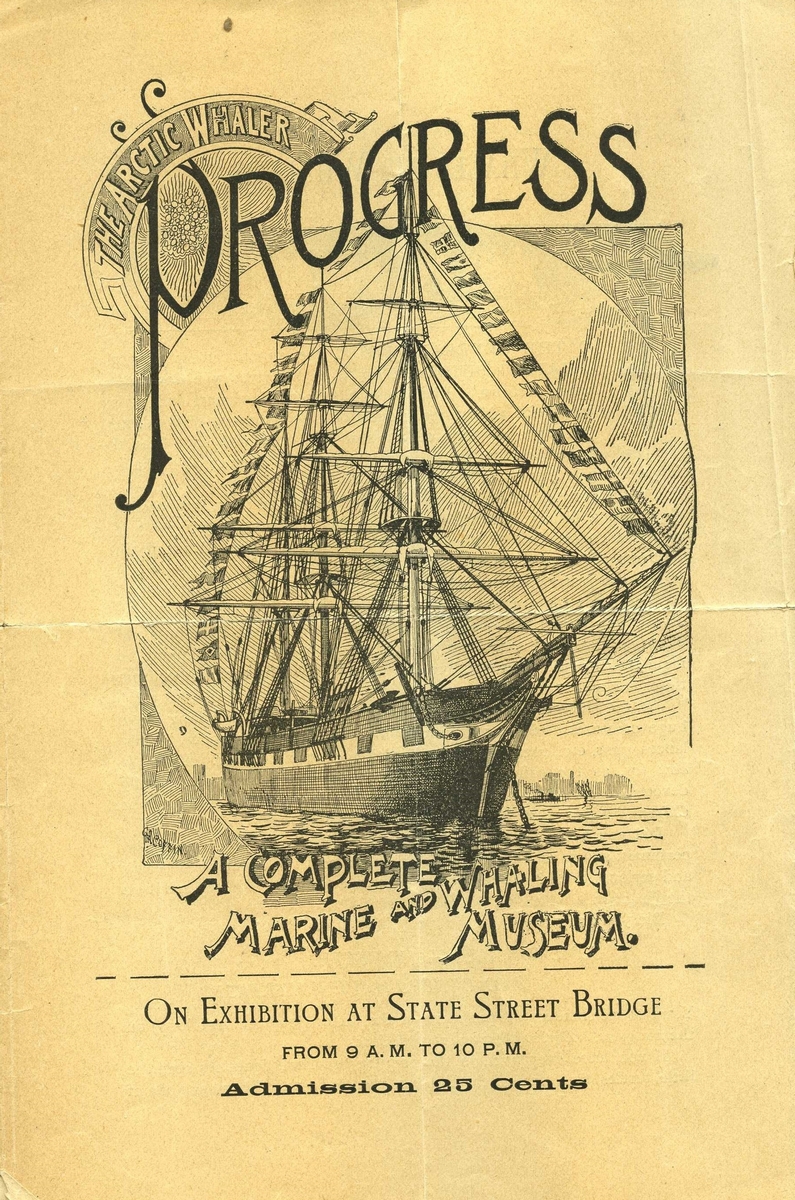

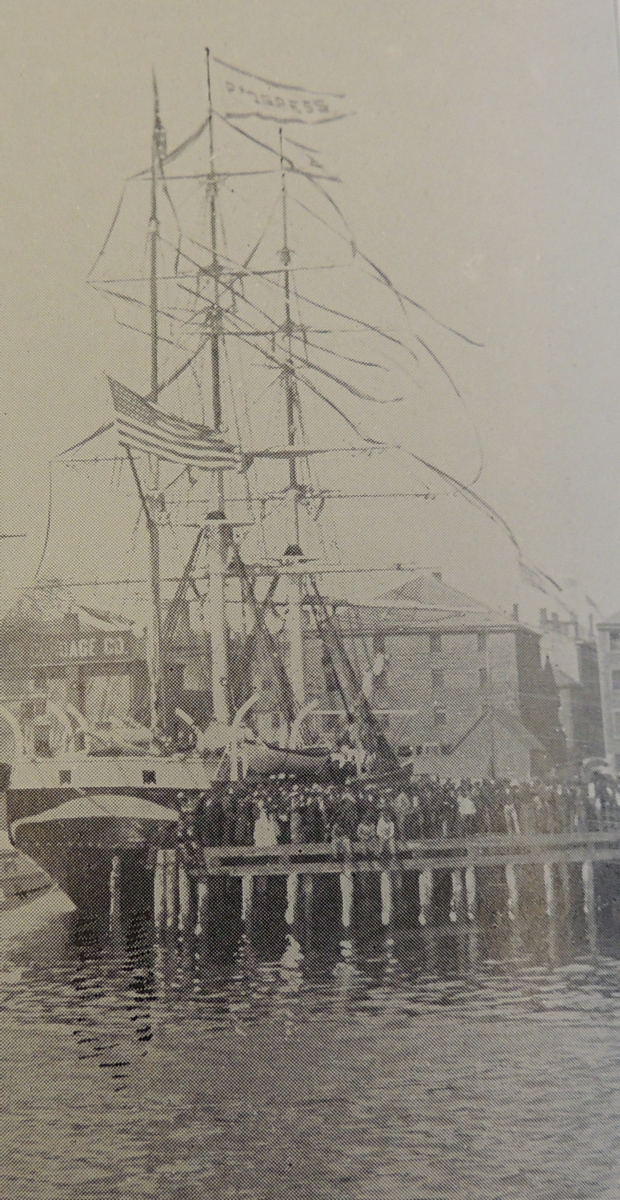

I think I was particularly taken with this description because I myself was holding onto an odd tale that I wanted to tell one day, one that I had discovered years earlier in the obituary of my great-great-grandfather, a whaling captain. At the height of the Gilded Age, a Massachusetts whaling ship called Progress traveled from New Bedford to Chicago for the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893 and was displayed as a whaling museum. However, the entire enterprise was a financial failure, with the whaleship eventually dynamited in Lake Michigan. Peculiar moments in the past, indeed.

The Progress became my classic “back burner” project. Over the years, scraps of research became files, then binders, then boxes. Eventually I committed to telling the strange tale of a whaleship’s final voyage to America’s heartland. I considered many genres, from a travelogue retracing the journey to a memoir of my whaling ancestor. But I kept returning to the idea of microhistory and its strength in using “strange and bizarre events” to create layers of meaning and context. Now, nearly two decades after I was introduced to the genre, the Progress finally sits at the center of my new book, The Last Voyage of the Whaling Bark Progress: New Bedford, Chicago, and the Twilight of an Industry (McFarland Press, 2020). Not only was it the right choice for my book, but it made me an advocate for even more microhistories in public history and the study of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era.

Using the Microhistory Approach

Jill Lepore wrote in her 2001 reflection on the microhistory genre that the value of examining something or someone so specific “lies in how it serves as an allegory for the culture as a whole.”[2] Or, as Thomas Cohen offers, microhistory moves the reader from the peculiar to the historically meaningful by revealing: “This story is a wonderful illustration of the following…”[3] In the case of the Progress, the allegory/illustration was about whaling itself.

By the 1890s, the American whaling industry was in precipitous decline, a ghost of its former midcentury glory days. The whaleship in question had been named “Progress” decades before, but now that word was connected to New Bedford’s rapidly expanding cotton manufacturing trade, not whaling. A floating museum at the fair further symbolized how the industry was being relegated to the past, even as limited whaling continued out of New Bedford.

Then there was the allegory of the museum’s spectacular failure—one so ignominious it took fire and dynamite to finally end it all. If history has famously been written by the victors, what was to be gained by using microhistory to extrapolate from such a fiasco? But I came to see the Progress as a wonderful illustration (to borrow from Cohen) of a cautionary tale. Right now, curators and archivists are tackling questions about memorializing industries in transition such as steel, coal, and manufacturing. By looking at what had gone so horribly wrong with one 1890s museum failure, I hoped to more fully illuminate the challenges that still confront public historians and museum professionals today.

The Opportunities and Pitfalls of Microhistory

Akeia Benard, curator of social history at the New Bedford Whaling Museum, recently described The Last Voyage this way: “It’s a story about the bark Progress, but it’s really not.”[4] I thought this was an excellent description of what microhistory attempts—a not-so-hidden agenda to venture into cultural and social history. Put another way, Francesca Mari posits that microhistorians use “small frames to convey ever larger pictures of truths.”[5]

For example, one chapter looks for deeper meaning within the products of the whaling industry—oils, candles, and lighthouse fuel. All quite literally pushed back darkness. This was significant because the whaling industry’s scions were primarily Quakers (Religious Society of Friends), a religion deeply infused with metaphors of light and dark. Looking at these religious undertones, it became evident that New Bedford had slipped into a sort of industrial hagiography for whaling. This explains how many families maintained an evangelical zeal for the trade, even as it declined. It also showed how they could remain unaware that not everyone would share such fervor for their august industry.

My book tackles questions of myth-making, historical memory, representation and commemoration—all topics historians regularly and admirably explore without using microhistory. So why bother? In the end, my experience revealed strengths of the genre I had not appreciated beforehand:

- It forces a historian to hone their storytelling ability. Beginning with something seemingly odd or eccentric is a classic “where is he going with this?” gambit. The process of successfully leading readers from those small frames to larger truths, while challenging, made me a better writer and scholar.

- It invites greater narrative freedom. In my book, the reader explores several chapters before they actually begin to follow the Progress’ 1892 final journey from New Bedford to Chicago— ostensibly the topic, as the title suggests. But microhistory allows, even encourages, these forays from the central event because, as Dr. Benard noted, it is about much more than that.

- It creates space for far-ranging research. By pursuing such a singular, “micro” story and its prism of contexts, I was able to dive into every related source no matter how tangential it first seemed. Ephemera, fair guides, photographs, court records, children’s literature, incorporation documents, bank records, letters, diaries, annual reports, scrapbooks and more—all were woven back into the Progress’ final voyage.

Still, of the various “Houses of History,” microhistory can be most directly challenged by the dreaded “so what” question. Why should one care about such an obscure, idiosyncratic story, and in this case, a story about something that didn’t even work? Yet it was precisely this approach to writing the book that allowed me to see the larger stakes involved in a little-known museum from the 1890s—the allegory for the whole, as Lepore suggests. Ultimately it was through microhistory that I came to realize just how relevant the Progress’ message is today.

How the Story Ends and Lessons Learned

Once the Progress’ last voyage began, the harbingers of the museum’s future difficulties began to quickly accumulate. The Progress had been sold to a Chicago syndicate, led by a coal baron named Henry Weaver. New Bedford’s whaling community assumed the museum they envisioned would be a faithful and didactic paeon to their heritage. Instead, as the shipboard museum moved further and further away from saltwater, it became something else entirely. By the time the whaling bark arrived in Lake Michigan, Weaver and his partners had transformed it into a museum of exotica, oddities, and maritime bric-a-brac. A banner announced “10,000 marine curiosities between decks,” and even the New Bedford whaling crew had been replaced with costumed freshwater sailors from Chicago. Once at the Columbian Exposition, it failed to entice visitors to pay 25 cents to come aboard. Abandoned and left to rot, it was finally blown apart by a demolition team nine years after the fair ended.

Working to tie this story to larger themes and “the culture as a whole” made something crystal clear: the importance of community. The Progress failed precisely because it was a museum literally unmoored and cast adrift from the community that originally conceived it. Ultimately, I hope that historians, and public historians especially, can extract value from a history that speaks to how we should exhibit an industry and people in transition. Museums, documentaries, and memorials—particularly those dedicated to a declining or perhaps defunct industry—need to be deeply rooted in the communities that surround them. Their success as modern cultural institutions hinges on partnerships and collaborations with the workers (or their descendants) that they are interpreting and commemorating.

Finally, using microhistory to explore this obscure museum brought the entire project full circle. The genre I have described is exactly what museums do every day. Curators use singular objects or stories to explain larger historical narratives. This, too, was a failure of the Progress. The objects were never used as “small frames to convey ever larger pictures”—of whaling, of a people, of a way of life. But this is what public historians learn to do as they master their craft. Such a sensibility grows from the practical tasks of working with artifacts, oral histories, and biographies and then connecting these in a deliberate way to a museum’s varied constituencies. Having completed my own contribution to the genre I believe we need more scholarship that capitalizes on this synergy between microhistory monographs and the products of public history. Ultimately both can further connect us to the complex and multilayered years of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era by bringing to life those “especially peculiar moments in the past.”

Dr. Daniel Gifford

Daniel Gifford is a public historian who focuses on American popular and visual culture. He received his PhD from George Mason University in 2011. His career spans both academia and public history, including several years with the Smithsonian Institution. He currently teaches at several universities near his home in Louisville, Kentucky.