By Jean-Louis Marin-Lamellet, PhD

September 15, 2020

This post is part of a series exploring the lived experience of Americans during the 1918 flu pandemic. Read the other posts in the series here.

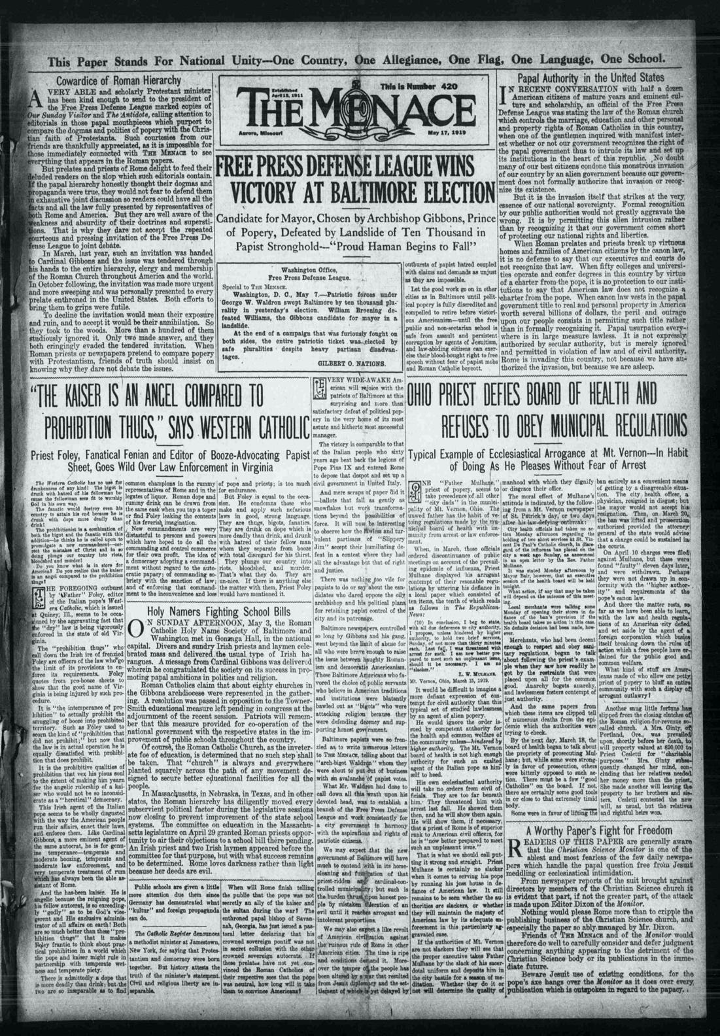

I encountered the 1918 flu epidemic while reading a weekly from the small town of Aurora, MO: The Menace (figure 1). The Menace was the most successful anti-Catholic newspaper in the 1910s: it regularly reached over one million readers. Some of the issues its news coverage of the flu raised still resonate today—conspiracy theories, fake news, sensationalism, scapegoating, fear of death, anxiety over the end of the USA and hopes for miraculous treatments—even if political targets and alliances have changed. Chinese Americans, not Catholics, are now blamed for the virus. Protestant evangelicals no longer see Catholicism as a threat and have largely aligned with conservative Catholics in opposition to liberals. Collusion between political leaders and religious organizations—which The Menace dreaded as Catholics churches allegedly sought religious exemption from closing order—has ironically come to pass. Conservative bigots do not defend closing orders as part of a patriotic duty anymore, as The Menace did. Instead, they argue that “the failure to exempt religious services from the general rules during the coronavirus pandemic constitutes an anti-constitutional attack on religion.”[1] President Donald Trump has turned the pandemic into a new chapter of the culture war and partisan polarization. In the 1910s, the culture war The Menace was waging opposed “Protestant patriots” to “Catholic traitors.”

Week after week, Menace journalists claimed they “exposed” “politico-ecclesiastical Romanism” and its “un-American campaign to make America ‘dominantly Catholic.’”[2] They saw Catholicism as culturally incompatible with American democracy, since as they imagined it, Catholics’ allegiance went to the Pope, in other words autocracy. Although World War I exacerbated anti-Catholics’ “ideological nativism” and their fervent displays of patriotism, the war also “shifted readers’ attention from internal Catholic threats to external tensions overseas.”[3] Beyond that, the war gave Catholics the opportunity to show their loyalty to the nation. This context is important to understand how The Menace responded to the 1918 flu epidemic. The Aurora newspaper was not particularly interested in the pandemic itself. The disease and the suffering it entailed only made the pages of The Menace as yet another example of Catholic subversion and the decline of the newspaper made it all the more rabidly conspiratorial.

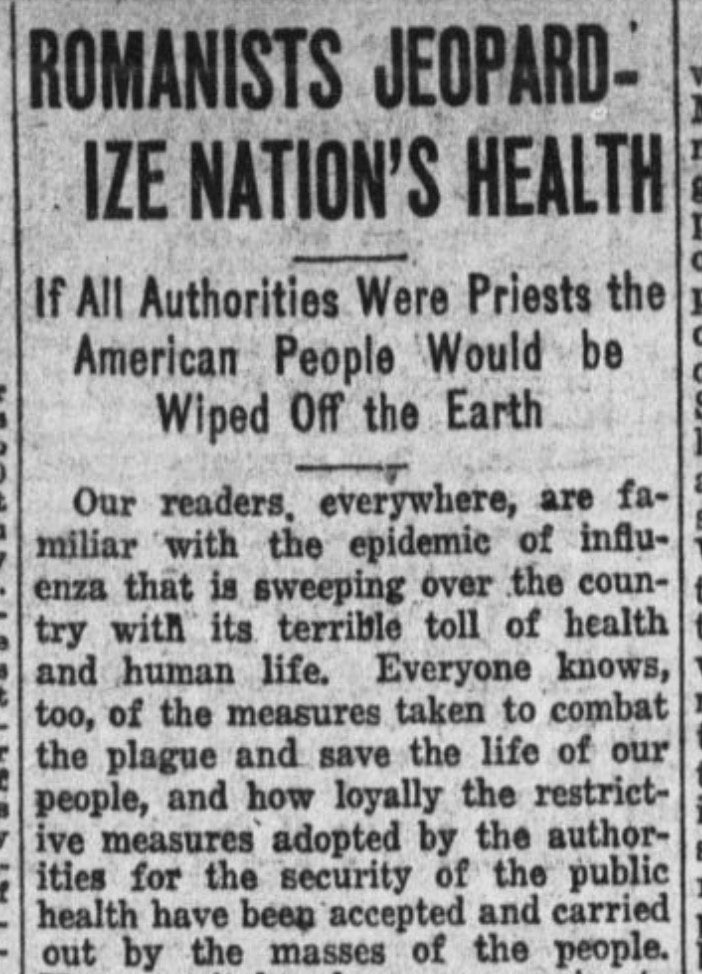

According to The Menace, the flu epidemic revealed, yet again, that Catholics were trying to undermine American institutions. The violation of lockdown rules was the most recurrent target. The newspaper kept contrasting treacherous Catholics with patriotic Protestants. Priests celebrated Masses in spite of closing orders whereas Protestant churches followed the rules.[4] Likewise, Menace lecturers suspended their tours.[5] The Menace essentialized Catholic believers, whom they saw as incapable of self-government, and their leaders, whom they denounced as lawless authoritarians. For instance, in Springfield, MO, a priest admitted churchgoers “by a rear door,” even though the city was “hard hit” by the epidemic. The selfish priest was arrested but not charged because “there was no penalty clause attached to the closing order.” The Menace recognized that some priests did obey the closing orders, but only when instructed by their superiors, as opposed to the “legally constituted authorities.” In contrast, Protestant churches supposedly accepted the regulations “voluntarily” in order “to save the life and health of the nation” (figure 2).[6]

Protestants embodied the “New Reformation” the editors had been calling for since 1916. In their view, the country was witnessing a revivalist movement of self-governing, militant citizens, the vanguard of a new Great Awakening.[7] After the US entered the Great War, only these Protestant patriots could “make the nation safe for democracy,” extending Wilson’s international crusade on the home front.[8] Near the newspaper’s hometown, in Verona, MO, “the youth of the village” performed this supercharged patriotism when they punished the priest who disregarded the closing order by painting the church yellow. Militant Menace readers also took part in the Protestant patriotic mobilization by sending clippings and letters telling of priests’ “deliberate violations” of municipal ordinances and orders of boards of health. For readers nourished on news stories of a Catholic plot to replace “civil law” with “the law of the church,” these violations were further evidence of conspiracy and their duty was to blow the whistle.[9]

For The Menace, the most unacceptable feature of Catholicism was the Church’s alleged self-perception as above the law. For instance, in Ft. Madison, IA, the mayor closed all schools, theaters, churches and prohibited all public gatherings (figure 3). However, one Roman Catholic priest “saw fit to violate this order by holding two services or masses or whatever they call them. Every other [Protestant] church in town lived up to the order with the exception of this one.” Leaving aside the withering contempt for Catholic practices, the article emphasizes Catholic authorities’ blatant disregard of the law:

The [mayor’s] order stopped the high school boys from playing football, stopped the boy scouts from holding their meetings, stopped the registered men who expect to be called to camp soon from drilling on the streets, but still this priest thinks he can hold out of door services.

The article stresses civic-minded actions by Protestant male members of the community, highlighting Catholics’ alleged non-compliance with the ideal of patriotic manhood. The journalist also notes that the priest’s “loyalty” had been “questioned by a number of Americans previous to this incident.”[10] Indifference to the law signaled treason.

For The Menace, Catholics could not but rely on treachery. For example, Catholic prelates refused to conform to the “closing order” in St. Louis, a “wise precautionary measure [that] will help check the ravages and heavy death toll of the epidemic.” The article excoriates the quibbling duplicity of Catholic authorities who explained the closing order banned public services but not private masses: priests should not announce mass beforehand and “should it so happen” that if a few people were in the church, they would “of course” hear Mass. Catholics also allegedly flouted naturalization laws, since “Roman prelates enjoy the rights of citizenship while boasting an alien title of nobility [Monsignor] conferred by their enthroned and crowned autocrat in the Old World.” As “alien aristocrats,” they secretly worked for an “alien empire push[ing] its juridical system in our midst to defy the legally constituted authorities.” [11] The Pope had higher authority than health boards. These “agents of alien popery”—a.k.a. “agents of a foreign corporation”— displayed “arrogance and contempt for civil authority” and broke down rules designed “for the public good and common welfare.” The Menace reframed old antipapist prejudices in Progressive terms: Catholicism was a “trust” and a corrupt “machine.” The fight against “Romanism” was a logical continuation of the fight against corporate power and political bosses.

Lawlessness, like the flu, seemed contagious. In Mt. Vernon, OH, The Menace claimed, stores started opening when owners saw churches did not abide by the closing order.[12] The consequences of this subversion were dire: “social and legal anarchy.” Catholics considered the rules of the Church to be above the “civil law” and, in case of conflict, appealed their case to state supreme courts. They framed the issue as a constitutional infringement on religious freedom. For The Menace, this would subordinate legislative power to cultural considerations. If Catholics could refuse closing orders on religious grounds, there was every reason to believe that they could ignore prohibition and reject public schools. The Catholic Church would have the privilege to “make its own laws” and “set aside [common laws] at their pleasure.” And “privileged interests,” The Menace kept emphasizing, was the antithesis of Americanism.[13] In brief, Catholics were seditious, undemocratic and un-American.

In 1919, a coercive and defensive style of patriotism blended the Catholic with the German threat. The Menace reported a wild story of German spies dressed as “black-garbed Sisters of Charity” traveling throughout the US with cultures of spinal meningitis germs. Such a machination could well account for the otherwise unexplainable devastations of the “Spanish influenza.” In an example of what historian Richard Hofstadter once labeled the “paranoid style,” this conspiracy theory revolved around imagined deadly threats, secrecy, deception (with cross-dressing as a more insidious and dangerous subversion of the traditional order), scapegoating, and confirmation bias. Since the spies threatened the nation, they had to be Catholic. Catholics were so alien that they were not only unassimilable but also literally inimitable. Only Catholic spies could perform a Catholic identity and “successfully carry on the deception.” Since nuns “had an open sesame to the camps” where so many died, they had to be responsible. The Menace could not acknowledge nuns’ exceptional sacrifice during the pandemic. In anti-Catholics eyes, this amounted to fake patriotism.[14]

Although the fear of a Catholic conspiracy permeated every Menace article, the fear of the disease also shone through the margins of the scandal sheet, as shown by the many patent medicine and alternative medicine advertisements promising to cure the flu. One advert about “drugless methods” revealed the “truth about influenza.” Just as for the Catholic menace, exposure of hidden truth offered remedies for the flu (figure 4).[15] However, The Menace completely distorted the muckraking tradition it claimed to preserve when they “exposed” Catholic wrongdoing. Anecdotal evidence ignored all the instances of Catholic churches closing and Catholic Sisters taking up the flu fight.[16] The Menace singled out Catholics as opposing public-gathering bans, even though many others resisted health regulations. The lines of resistance were less ethnic, racial, and religious than administrative (city vs. state health boards) and economic (controversies over what seemed essential activities—stores, for example—and unessential activities, such as churches or public amusements).[17] The Menace’s final article about the flu was more factual and retrospective: as a result of the epidemic, the Catholic Mutual Benefit Association could not pay the “death claims of $580,000” and had to levy “extra assessments” to reduce the deficit.[18] As the third wave was beginning to subside in June 1919, the subject did not seem to interest the newspaper anymore. The Menace plant eventually burnt down on December 11, 1919, thus putting an end to the newspaper’s career.

Cover Image

The Menace front page, May 17, 1919. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

Jean-Louis Marin-Lamellet, PhD

I received my PhD in American studies from Université Lumière-Lyon 2, France, in 2016. My research focuses on the interplay between print culture and protest movements at the turn of the twentieth century. My dissertation used Boston reform editor Benjamin O. Flower’s trajectory from champion of progressive causes to “medical freedom” advocate and anti-Catholic crusader as a case study to analyze the ever-changing and contested definitions of “progress,” “freedom,” “science” and “the people” from 1889 to 1918. My current research focuses on the representations and receptions of Populism, the long history of anti-monopoly, and the use of periodicals by the radical middle-class to further their political goals. I teach at Université Savoie-Mont Blanc, Chambéry (France) and in high school.