By Thomas MacMillan

August 18, 2020

The recent uprisings for Black lives have led to calls for the restructuring of society. The principal targets have been urban police forces, which have received lavish funding and organizational impunity for many years. However, these forces are beginning to be held accountable by those they purportedly serve. The actions of protesters have even brought the potential of police abolition to the mainstream conversation for the first time. Abolitionists argue that by using public funds to meet a community’s needs, the senseless violence commonplace in the country’s legal institutions can be mitigated or eliminated. While police have been the primary target thus far, other institutions, especially public schools, have begun to receive more attention. Public education, like the police, has long been used to discipline and assimilate workers, immigrants, and indigenous communities and thus protect racial capitalism. Since their founding, both the police and the common school were created to achieve this result. Even though Catholic schools were far from hubs of revolutionary activity, their tolerance for linguistic and culture diversity frightened the country’s increasingly nationalist and primarily Protestant ruling class. By winning the struggle against Catholic mission schools, the industrialists who funded and controlled said movement were able to impose a version of Americanism upon subaltern people which undercut those groups’ potential opposition to white supremacy and industrial capitalism. Lastly, I argue that the Movement for Black Lives and the larger Black Freedom Struggle are wise to argue for a systematic democratization rather than piecemeal reforms.

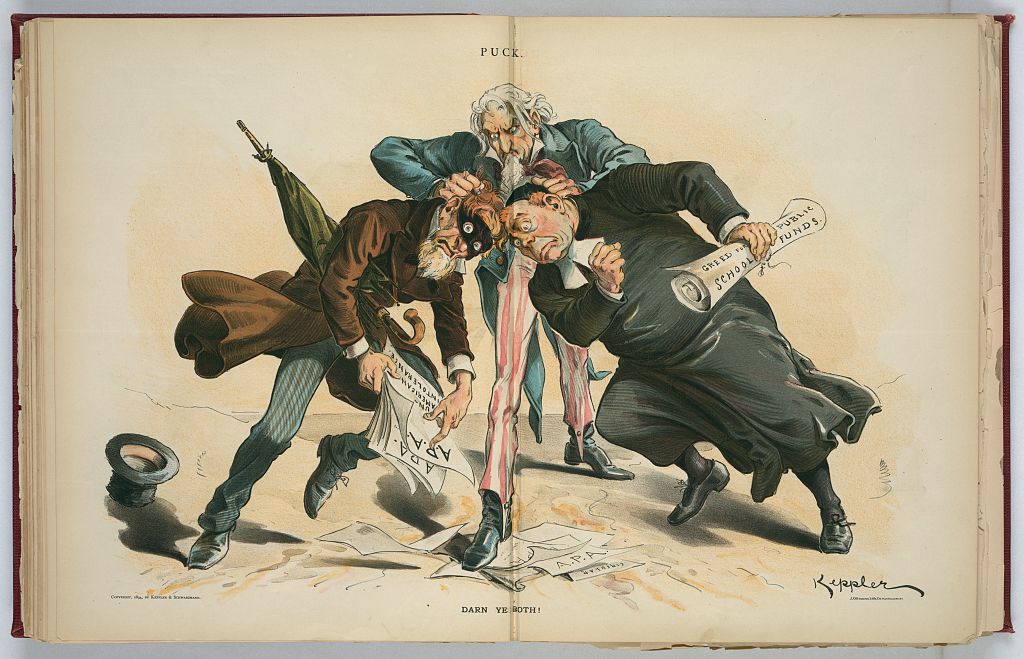

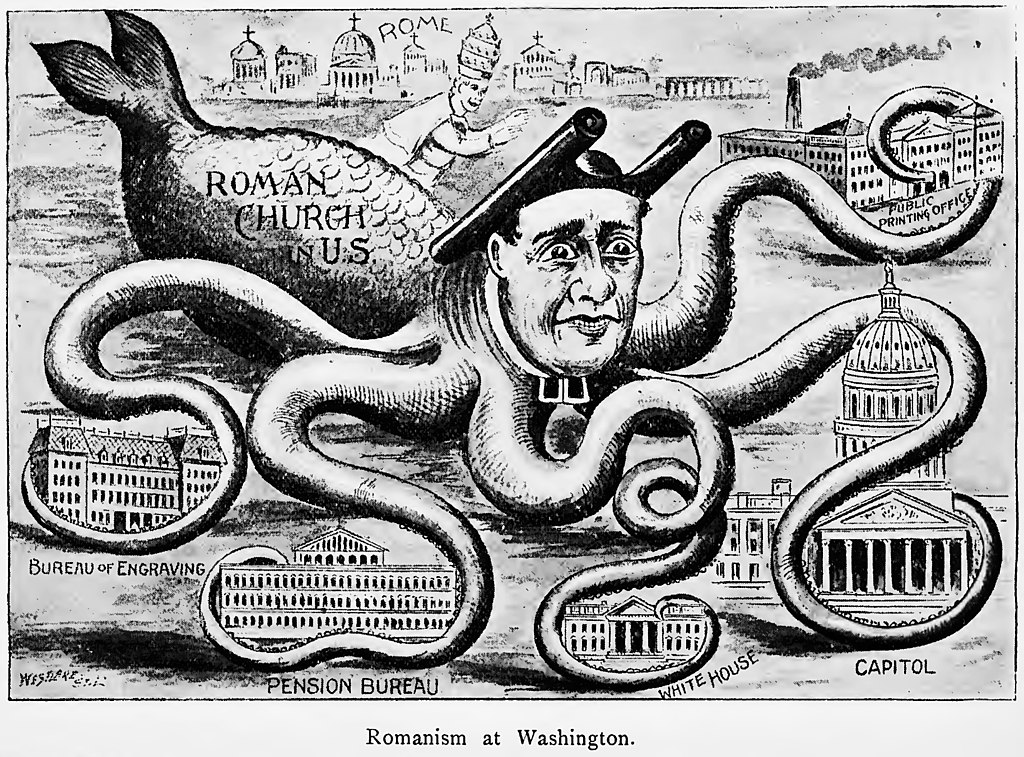

More than a century ago, Protestant activists sought to ensure that public funds would protect Protestant-dominated common schools from the increasingly diverse racial, ideological, and economic landscape of the late nineteenth century. One such group, the National League for the Protection of American Institutions, maneuvered to redirect public funds away from Catholic institutions. In the last decades of the nineteenth century, many white, property-owning and English-speaking Protestants were concerned that their dominant social position was beginning to feel tenuous. The movement that arose as a result has commonly been described as “Anti-Catholicism,” but is probably more accurately described as Protestant supremacism.[1] At their peak, groups promoting this idea counted 4 million supporters. The most prominent was the American Protective Association (APA). The APA was a secret society composed primarily of working- and middle-class Protestants which used electoral politics and consumer boycotts to punish Catholics and other presumed ‘foreign’ ideologies. However, the APA, like the Know-Nothing movement of a generation prior, had limited impact among elites because it was a secret society and thus was unable to be publicly scrutinized.

The most influential public organization was the National League for the Protection of American Institutions. This group advocated a sixteenth amendment to the Constitution. The proposed law would have barred governments from providing financial support to organizations run by churches. While a number of states adopted the National League’s proposed amendment into their own constitutions, the group’s greatest triumph occurred when it secured the end of direct financial support for parochial schools via Congressional act. Though the National League was explicitly nonsectarian and nonpartisan, its members were overwhelmingly evangelical Protestants. They sought to ensure that public schools would teach immigrants and Native Americans the values necessary for the maintenance of white supremacy and industrial capitalism. The importance of the National League and the larger Protestant supremacist movement of this period lies in their ability to successfully enforce a Protestant supremacist vision onto educational and non-profit institutions. This success prevented these institutions from being democratized by subaltern groups. As such, this organization’s forgotten history helps contextualize our current social context and provides numerous possibilities for future research.

Origins

The origins of the National League date to the question of public financing of parochial schools. Starting in the 1870s, the mass immigration of Catholics, Jews, and other non-Protestants resulted in the mass growth of religiously-run institutions. Segregated into their own communities, migrants from Quebec, Ireland, Italy, Poland, and the Spanish-speaking Caribbean developed their own linguistic and cultural organizations. Similarly, Mexican Americans and indigenous peoples in the Southwest had a long tradition of doing so. Noticing this trend with alarm, elites were simultaneously concerned with their ability to reshape the West. This was evident in an 1875 speech by President Ulysses Grant in which he called for a Constitutional amendment banning appropriations to religious institutions, including charities and schools. Soon thereafter, House Speaker and presidential hopeful James G. Blaine submitted to Congress an amendment soon named in his honor. This proposed 16th amendment included Grant’s suggestions but also, in an effort to satisfy Protestant supremacists who feared secularism, guaranteed that “the reading of the Bible shall not be prohibited in any school or institution.”[2] This provision directly challenged cities with large Catholic populations which had successfully lobbied school boards to eliminate religious services from their curriculum. The amendment won majorities in both the House and Senate but failed to garner the requisite two-thirds in the Senate and thus was not sent to the states for ratification. Defeated at the federal level, the fight against parochial schools returned to the states. New York, as the most populous and politically powerful state, was one of the leading sites of conflict. In the mid-1880s, an informal coalition formed of Protestant elites, including clergy, academics, businessmen, and Wall Street bankers. Organized to fight against the type of “machine politics” which had successfully eliminated Bible-reading and hymn-singing from urban public schools, this group eventually became the National League for the Protection of American Institutions.

The National League was formed in 1889, shortly after Benjamin Harrison recaptured the presidency for the Republican Party. While officially non-sectarian, the board’s 20 members included no Catholics and only a token Jewish member. Unlike the Know-Nothings and the Ku Klux Klan, the group emphasized their relative inclusivity by putting forth Norwegian-born H. H. Boyesen, a well-known Columbia University professor, as an early spokesperson.[3] Opponents described the group as being “composed chiefly of very respectable men, some of whom have great wealth and influence,” which distinguished them from the secretive and lower-class American Protective Association.[4] One such member was John C. Jay who was a grandson of the founding Supreme Court Chief Justice. Like his grandfather, Jay was openly hostile to Catholics. In a speech given at the group’s founding retreat and reprinted verbatim in the New York Times, the younger Jay opined that French Canadian immigration to New England, combined with the existence of Catholic parochial schools, would mean that “the home of the Pilgrims” would “be treated as a conquered province of the Vatican.”[5] Besides clergy and academics, the National League’s board also included many of the country’s leading industrialists and bankers, among them the President of the Bank of North America and a leading paper magnate. An 1891 petition to Congress listed former President Rutherford B. Hayes as well as industrialists Andrew Carnegie, John D. Rockefeller, and Cornelius Vanderbilt as supporters.[6] Rockefeller, in particular, was a major donor to the cause.

Objectives and Rhetoric

The rhetoric of the National League belies the group’s larger objective. At face value, the group’s public position claimed that it was formed to keep the “functions of the Church and the State…distinct and separate” and that the public financing of any religious institution constituted a violation of the First Amendment.[7] However, it understood that public school curricula included mandatory use of Protestant-inspired education, including the use of Protestant prayers and hymns and the reading of the King James Bible. Among their arguments for doing so included concerns about the disloyalty of indigenous people. For instance, arguing against Catholic missions on reservations, it claimed that “Indians are taught [by Catholic missionaries] that the US government is not their friend…” Moreover, it argued that “sectarian instruction…has kept the tribes among whom it has prevailed helpless dependents.”[8] Underlying this rhetoric, opponents of missionary-run schools believed that common schools, under the direction of the United States government, would be able to sufficiently “Americanize” immigrant and indigenous children. To Americanize meant instilling the values of patriotism, private property, imperialism, and patriarchy.

Results

Funding for mission schools declined rapidly during the second Grover Cleveland administration (1893-1897). After peaking in 1893, a combination of the National League’s sustained public pressure and an economic depression starting in that same year led Congress to pass the Indian Appropriations Act in June 1896. This act banned funding for mission schools except on a contract basis. The group’s lobbying efforts occurred not just on the federal level but within the churches themselves; federal funding had always gone to both Catholic and Protestant sects. However, in the years prior to 1896, the National League had successfully convinced the largest Protestant sects to reject federal funding in a bid to isolate the Catholic Church. Thus, by 1896, the Catholic Church received over 80 percent of all allocated funding. When the funding was eliminated entirely in 1900, the Catholic Church was the only large recipient of funds and federal funding for mission schools. Around the country, it helped secure the incorporation of appropriation bans in 13 state constitutions, mostly in the South and West. The National League continued to advocate for a constitutional amendment after 1896; however, having achieved a partial but major portion of its program, it declined until disappearing in the first decade of the 20th century.[9]

The National League’s greatest impact was upon the education system of Native Americans. For centuries prior, mission schools located in or near their own communities had been the primary method of western instruction for indigenous people. However, many were forced to close due to lack of funds which proved to be a boon for the rapidly growing and boarding school movement. With few options remaining and a federal requirement that their children attend formal schools, many Native parents were forced to send their children to far-away boarding schools. It is vital to recognize that, regardless of which institution ran the schools or where the money derived, this process ushered a new form of violent settler colonialism against the indigenous people of North America. In the end, educational funds were transferred to the white Protestant-dominated common school movement, where they were used to prepare indigenous and immigrant children for their role as docile workers in the growing capitalist economy.

The Movement for Black Lives calls for community control over public education in addition to policing. It is not a coincidence that the country’s leading Black Freedom Movement organization ties these issues together. Mass protests, from Minneapolis to Portland and around the world have stressed the need to alter the structures which perpetuate racist violence. The paternalistic fight between Catholics and Protestants over who would school immigrants and indigenous peoples in Americanism in the 1890s provides a cautionary tale against top-down reforms which do not center those most harmed by public institutions. As the Black Freedom Struggle continues to expand, it is vital to emphasize the necessity of altering the structures created by those white Protestant supremacists who shaped American citizenship during the Gilded Age and Progressive Era. A flowering of democracy would tear down not only racist statues and force the redistribution of police budgets but ensure the rights of all people.

Thomas MacMillan

Thomas MacMillan is a PhD student in History at Concordia University in Montreal. His research explores the history of immigration, radicalism, and working-class transnationalism during the twentieth century. He received a MA in History from the University of Maine and a BA in International Development and Social Change from Clark University (Massachusetts).