by Dr. Tamara Venit Shelton

September 25, 2019

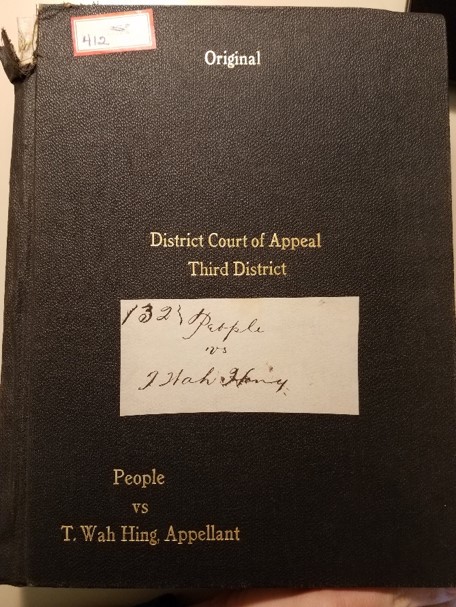

In 1909, T. Wah Hing was indicted for feticide. At that time, forty-year-old Hing had been practicing traditional Chinese medicine for more than two decades in a home and office on J Street, between Seventh and Eighth in Sacramento, that he shared with his father, an immigrant from China who went by the same name.[1]

Chinese doctors practicing in the United States like T. Wah Hing terminated unwanted pregnancies for their patients when abortion was illegal and the American Medical Association (AMA) officially opposed its practice. Between the 1860s and 1880s, new laws that criminalized abortion and made it illegal to circulate information about birth control across state lines spread across the country with the support of regular physicians.[2] Prior to that, abortion before fetal movement (“quickening”) was mostly unregulated, while abortions after fetal movement considered high misdemeanors in cases of maternal death. Members of the AMA encouraged the suppression of women’s access to birth control and abortions as part of a larger “social purity” campaign as early as the 1850s. Certainly, there were individual regular physicians who performed abortions or offered advice on avoiding pregnancy, but as a professional class, their public statements tended to link birth control with female promiscuity. It was not until the era of the Great Depression that regular physicians publicly supported efforts to educate women on family planning and agreed to provide contraception at specially designated clinics.[3] In the Progressive Era, however, American medical science seemed designed to discourage women from making choices about their reproductive life.[4]

As detailed in my forthcoming book, Herbs and Roots: A History of Chinese Doctors in the American Medical Marketplace, abortion was just one of many services Chinese doctors offered to their female patients in the Progressive Era United States. Chinese herbalists had been among the first immigrants from China in the 1850s. Over the next decades, they served Chinese and non-Chinese patients in their apothecaries, where they performed diagnosis by pulse and compounded traditional remedies. As early as 1880, Chinese doctors regularly advertised specialization in the “diseases of women,” which might include cancers, venereal diseases, menstrual pains or irregularity, infertility and pregnancy, or other less specific ailments.[5]

The study of women’s diseases and recommendations for childbirth had been part of the mainstream Chinese medical canon and training in the imperial palace since the Song dynasty (960-1279). Imperial scholars, steeped in Confucian philosophy, considered the health of wives and mothers as crucial to the health of the empire, which was founded on a familial model.[6] With regard to pregnancy, Chinese doctors were philosophically pragmatic. In the late Qing period, when mass immigration from China to the United States began, popular manuals on women’s health advocated noninterventionist approaches such as herbal remedies and prayer to cope with infertility and childbirth and the termination of pregnancies that risked the health of the mother.[7]

In 1909, the state of California claimed that Hing used a “long tongue-shaped instrument made of a hard and nonflexible substance… about fifteen inches in length and shaped like a common round lead pencil” (possibly a curette or uterine sound) to induce a miscarriage in Lottie Phillips. Phillips was three-months pregnant but only one-month married to a local clerk, William Phillips, who may or may not have fathered the fetus. On June 25, 1908, Lottie Phillips and her mother, Mrs. Toomey, visited Hing’s office. Toomey stayed in the reception area while Phillips received a private consultation in an adjoining room. Phillips later testified that Hing asked her why she wanted to terminate her pregnancy, and she replied that her torso had been badly burned in an accident, and, as a result, she did not think she could breastfeed a child. Hing asked for a payment of twenty-five dollars, then directed the patient and her mother to a building nearby, on L and Sixth Streets.[8] Twenty minutes later, Hing joined them, took Phillips upstairs, presumably where he performed the abortion, and then sent her home to rest. Around one or two o’clock in the morning, she passed a large amount of tissue that may have been the fetus.[9] The following day, her condition worsened. It is not clear from newspaper coverage or the court transcript if she suffered from excessive bleeding or some other complications, but she was admitted to the county hospital and eventually recovered. Her doctors there encouraged her to file a complaint against T. Wah Hing.[10]

Hing’s case went to trial in November of 1909. His defense insisted that no one but Lottie Phillips had seen him use the instrument and that her testimony was in fact an effort to blackmail the physician. Moreover, the attorneys argued that Hing was not even in Sacramento on the day in question, and they produced eyewitnesses and a ledger with his signature from a hotel in Marysville, about forty miles away.[11] The prosecution countered with evidence from a Sacramento post office showing that Hing had signed for a letter on the same day.[12]

When the proceedings against Hing ended with a hung jury, a second trial was quickly convened. The Los Angeles Times described the retrial as a “carnival of perjury.”[13] The Phillips’ upstairs neighbor, Gertrude Hill testified for the defense that Lottie’s miscarriage had been self-induced. Another woman, identified in newspaper coverage as Mrs. George Gillespie, asked Hing to pay her $250 in exchange for persuading the Phillipses to abandon the case against him. After she failed to do so, she promised to produce a letter dictated by the illiterate William Phillips that would exonerate T. Wah Hing of all wrongdoing. Unfortunately, the letter went missing.[14] Meanwhile, Hing tried to pin the crime on other doctors and a female nurse, who may have performed abortions on C Street, but when the defense witness called to testify to that fact took the stand, he failed to corroborate the story and instead accused Hing’s attorneys of attempting to bribe him.[15]

On December 15, 1909, T. Wah Hing was convicted and served a three-year prison sentence in Folsom. Upon his release, he returned to Sacramento and continued to practice medicine for more than twenty-five years.[16] In that time, he was arrested repeatedly for practicing medicine without a license, for drug fraud, land fraud, and, repeatedly, for feticide. In 1917, the indictment was set aside, and in 1922, he was exonerated.[17] Prosecution did not dissuade him from terminating pregnancies for women in need.

It is impossible to say how many practitioners of traditional Chinese medicine in the United States included abortions in their roster of services, and it certainly was not the treatment most closely associated with herbalism in the American popular imagination. Nonetheless, T. Wah Hing’s story speaks to the appeal of Chinese medicine for non-Chinese female patients. In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, American women were both major consumers and practitioners of irregular medicine, including Chinese medicine.[18] The American popular press often portrayed white women as overly susceptible to “Oriental quackery” but ignored the ways in which western-style medical science failed to meet the needs of female patients. Irregular doctors like T. Wah Hing defended women from physically and psychologically damaging practices championed by their regular rivals. Perhaps most fundamentally, then, the case of T. Wah Hing suggests that for patients without recourse in mainstream medical care, Chinese doctors provided life-changing and life-saving treatment and procedures.

Dr. Tamara Venit Shelton

Tamara Venit Shelton is an associate professor of history at Claremont McKenna College. She is the author of A Squatter’s Republic: Land and the Politics of Monopoly in California, 1850-1900. This blog post is drawn from her forthcoming Herbs and Roots: A History of Chinese Doctors in the American Medical Marketplace, which will soon be available from Yale University Press.