by Dr. Kelly Marino

September 11, 2019

With centennials in 2019 and 2020 approaching, scholars are working to present the suffrage movement and its legacy in new ways. To date, most studies focus on national or state leaders who directed major organizations or accomplished well-known achievements. They often overlook local activism and less publicized campaigns that broadened the suffrage movement’s support base among ordinary Americans in cities and towns, particularly activism to interest the working class, a growing segment of the population whose endorsement was important to making the campaign less marginal and more mainstream.

Listed on a suffrage plaque in Hartford, Connecticut, is the relatively unknown Augusta Lewis Troup (1848–1920), an activist, reformer, teacher, and journalist who spent much of her life in New York City and New Haven, CT, where she campaigned to advance the rights of working women. A key figure in the state’s labor movements and local suffrage campaigns, Troup was exceptional for her unrelenting public engagement and ability to overcome personal tragedy to create change for her sex during a restrictive period. Not only did she set precedents for female typesetters and teachers, she dedicated her entire life to these causes. Troup grew from being a frail, cloistered Victorian to a self-supporting, internationally recognized, strong, modern woman. Not afraid to take contentious stands, she was a woman acting and thinking ahead of her time.

Augusta Troup (née Lewis) was born in New York City in 1848. Her parents died when she was a baby, leaving her to be raised as an orphan by Isaac Baldwin Gager, a Wall Street broker and commission agent in Brooklyn Heights. A prosperous businessman, Gager offered Troup many comforts and privileges customary for an upper-class Victorian girl. Rather than being sent to city schools because of her fragile health, Troup first had private tutors, then attended the elite Brooklyn Heights Seminary and later the Catholic Convent School of the Sacred Heart in Manhattanville, where she studied French, the classics, literature, and philosophy. She emerged cultured, exceptionally literate, and refined—characteristics crucial to her advancement when her circumstances changed.[1]

When Troup lost Gager’s financial support because of an unexpected economic depression in 1866, she was left to take care of herself. Using her good judgement, talents, and training, Troup succeeded not only in becoming a self-supporting woman but a leader for others of her sex. She landed her first job with the Courier des Etats-Unis, a French-language newspaper, and then worked at the New York Sun, where she received special assignments, such as interviewing social reformers and activists, including Victoria Woodhull, Lucretia Mott, Henry Ward Beecher, and Horace Mann. Troup made a name for herself studying and writing about contemporary politics, current events, and the problems of the industrial city. During an era of self-made men, Troup was a self-made woman.[2]

Troup then became interested in typesetting, a male-dominated occupation. She convinced the New York Era to allow her to work as an apprentice, and soon the New York World hired her. The World selected Troup to test the new Alden typesetting machine, and her proficiency with the technology made her invaluable. In 1867, men in the International Typographical Union (ITU) Local No. 6 struck. To deal with labor shortages, the World hired non-unionized female employees but paid the women less and fired almost all of them when the strike ended. Women were not welcome in the publishing industry or labor unions because of gender stereotypes that emphasized their inferiority and portrayed them as unwelcome job competition. However, the World saw Troup as an exception; she was the only woman not fired after the strike because of her experience using the Alden machine. Incited by the poor treatment of her female colleagues, she quit her job, and her career as a labor activist began.[3]

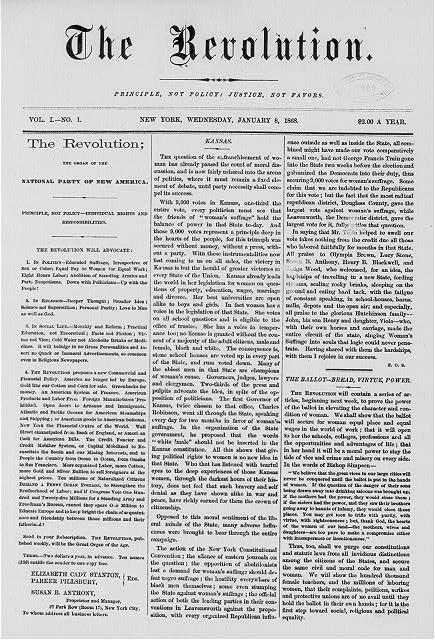

During the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, women’s presence in public and political spaces was increasing. It was not just working-class women who were entering traditionally homosocial spaces and male-dominated occupations; more and more educated middle- and upper-class women were challenging the confines of the domestic sphere out of necessity, drive, or a sense of duty. Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, active in the abolition campaign and the women’s rights movement, were gaining followers in the Northeast at the same time that Troup was developing a political consciousness and a concern for sexist injustices. Anthony realized that female typesetters and journalists, such as Troup, could be valuable in producing the media to fuel the national campaign for women’s rights that they were working to launch. Anthony and Stanton hoped to create their own newspaper with all female employees, not only giving women job experience but also making the publication symbolically powerful because it was produced by women and for women of different backgrounds. They established The Revolution with an all-female staff in 1868. Job opportunities at The Revolution initially attracted Troup and other women left unemployed by the World not only because it was a way to earn an income but because they supported aspects of the paper’s mission as well, which was to draw attention to the unjust circumstances faced by the female sex.[4]

Anthony and Stanton worked with the female printers to create the New York Working Women’s Association, a protective society for female labor, to improve their conditions and further win their support. The Association brought together working-class and middle-class women. However, as many scholars have noted, partnerships between the upper- and working-class women were difficult because of varied life experiences and class bias, which led to different perspectives and goals. Anthony and Stanton, having never worked in a factory or faced employment problems in the corporate and industrial realms, believed that women’s suffrage should be the primary goal of the group. With the vote, they argued, women would have greater power to create any change that they desired. As scholars suggest, to these women, gaining equal suffrage was the most progressive and radical change that they could obtain to better their plight—a great force that could help women of all backgrounds. Some scholars, however, have argued that the mainstream suffrage movement’s primary focus on the vote alienated important allies and limited the breadth of change that could be achieved by the campaign.

In fact, Troup and other working women disagreed with Anthony and Stanton in several key ways. They believed that although women should have equal voting rights, first and foremost, they needed to improve their grave economic and occupational situations. They saw the suffrage movement as a distraction from their labor agenda and advocated for a different type of women’s activism, one that put the needs of their class first. This led to divisions over priorities in the women’s movement that could never be reconciled either before or after the suffrage campaign. Troup and her followers further conflicted with Anthony and Stanton, who hoped that their new organization would support the rights of all working women, whether or not they were in a union. Pro-union women such as Troup resisted this plan as undermining their goals within their trade. Troup argued that all female labor should be unionized for the workers’ benefit. Rather than suffrage, Troup insisted, women’s primary objective should be admission to male labor unions to improve their plight.[5]

Troup’s background and experiences allowed her an unusual social and cultural knowledge of what it was like to live in privilege and hardship. However, rather than take up Anthony and Stanton’s ideals, which represented the culture in which she was raised, she was unwavering in her support of the ideologies of working-class women, whose daily circumstances she witnessed and related to on a deeper level. Her own personal experiences in the workforce shaped her agenda in a way that Anthony and Stanton’s could not. When their paper, The Revolution, fired Troup because of her views, she formed the Women’s Typographical Union Local No. 1 (WTU) of New York in 1868. WTU would be an all-female labor union that worked to be incorporated into the ITU’s all-male Local No. 6. Troup’s allegiances became even clearer in 1869. That year, during an event known as the “Book and Job Strike,” Local No. 6 struck in protest of non-union women taking their jobs for lower pay. Anthony and Stanton sided with the women, happy to see them infiltrating the male profession, while Troup and the WTU supported Local No. 6 and refused to cover the men’s jobs during the strike (refused to be “scabs”), showing class over gender solidarity.[6]

Solidifying their break from Anthony and Stanton and mainstream suffragists, the WTU’s action was a catalyst in getting their male counterparts’ respect in the labor movement. Grateful for the WTU’s support during the strike, some ITU men realized that including female members could benefit labor activism because if the women allied with the union, the companies would have fewer cheap strikebreakers. Alexander Troup, a member of Local No. 6, Secretary Treasurer of the ITU, and a progressive thinker, proposed that the WTU request a charter to gain admission to the larger ITU as “a kind of” female auxiliary. (Because of this action, scholar Ellen Carol DuBois writes that men are too often credited with women’s admittance to the ITU, ignoring the activism of women such as Troup.)[7]

Augusta Troup and supporters agreed to the compromise, eager to make any progress toward their primary goal of union acceptance. In 1869, she and a colleague attended the ITU convention in Albany to request official admission to the international labor union. Appreciative of the group’s work backing Local No. 6 in New York, the ITU approved their request, making the WTU’s admission to the ITU one of the first times in history that a male trade union approved a charter to recognize a female associated body. In 1870, the ITU gave Troup the position of Corresponding Secretary. Although a seemingly patronizing position, because no woman had ever held an executive office in the organization, it was actually another milestone for female typesetters.[8]

Augusta married activist Alexander Troup, the ITU member who had helped her and her organization, in 1872, and the couple moved to Connecticut to continue their activism. Alexander established the New Haven Union newspaper, which he worked on with his wife. The newspaper supported the Democratic Party and issues such as women’s suffrage, labor rights, and African American equality. Alexander also served as a federal tax collector for Connecticut and Rhode Island and was a member of the Connecticut legislature and Democratic National Committee. The couple had seven children.[9]

In addition to writing, raising a family, and helping with her husband’s newspaper, Augusta Troup reinvented herself to become a successful teacher in New Haven. Unsatisfied with the sexism in Connecticut schools, Troup became involved in several city campaigns. She was vice president of a New Haven school suffrage organization, reflecting her continued interest in questions of women’s working conditions and voting rights, and conducted urban canvassing for many related issues, including the election of female members to the Board of Education. Troup later helped to form the New Haven Teacher’s League in 1911 to examine issues with salary schedule, the pension system, tenure, and pay inequality in the city.[10]

Troup remained concerned about the working-class, the poor, and immigrant populations throughout her life. She lived with her husband in an area of New Haven inhabited by Italian Catholics who faced prejudice and discrimination. Realizing that a lack of English language and knowledge of the political and legal systems hurt the immigrants and laborers, she used her newspaper to publish articles on their behalf. Troup was nicknamed “Little Mother of the Italian Colony” for her efforts.[11] She remained active in suffrage, philanthropic, and educational endeavors until two years before her death. While participating in a charity event, she suffered from heat stroke, and her heart never fully recovered. Although she died on September 14, 1920, she lived long enough to see many of her ambitions for women in labor unions achieved and women’s suffrage become national law.[12]

Ironically, Troup died on the day that Connecticut legislators voted to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment, an extraordinary end to an exceptional yet underexamined life—one of the many grassroots stories that deserve our attention as we move toward painting a fuller, more inclusive picture of the campaign. Troup’s story—largely overlooked in the scholarship on the women’s suffrage movement because she did not head a national organization or create widely known legislative change—especially deserves our attention. It sheds greater light on the importance of the suffrage cause to working women, who subscribed to their own agenda and vision for women’s rights activism. By the early twentieth century, the women’s suffrage movement succeeded in creating legislative change because it had become a cause that diverse Americans, for varying reasons, had started to seriously consider and discuss. It had moved from the margins to the center of politics. Although all women (and men who supported women’s suffrage) might not have agreed on the tactics, arguments, or priorities important for shaping the campaign, their efforts to consider the women’s rights issue, even if in divergent and non-collective ways, still raised greater popular awareness and conversation about women’s suffrage. Troup’s activism is reflective of the important intersections between social and political movements that existed at the turn of the twentieth century and helped to shape the nature of the campaigns that would follow.

Dr. Kelly Marino

Dr. Kelly Marino is an Assistant Lecturer of History at Sacred Heart University in Fairfield, Connecticut. She researches the history of the women’s suffrage movement in the United States and has written several articles specifically about the movement for women’s right to vote in Connecticut.