By Dr. Cody Dodge Ewert

April 13, 2021

In his annual report for 1906, A. C. Nelson, Utah’s state superintendent of public instruction, proclaimed that the Beehive State’s schools must teach patriotism. “It is in our public schools that our national unity is to be conserved,” Nelson explained. Although Utah had achieved statehood a decade earlier, many outsiders viewed it with suspicion due to the outsized social and political influence of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, which, to the horror of many Protestant moralists, had sanctioned plural marriage until 1890. To assuage these concerns, educators in Utah made a point to emphasize what Nelson described as “American ideas” in the classroom.[1] By doing so, the state’s schools eventually earned praise from major outlets like the Journal of Education, which proclaimed in 1920 that Utah had “made greater strides in the fundamentals of public school education in thirty years than has any other state in the Union.”[2]

Yet, as the case of one Salt Lake City student reveals, Utah’s embrace of patriotic education should not be seen merely as a public relations ploy. Rather, by demanding that students regularly perform their loyalty to the nation, the state’s leading educators helped lay the groundwork for the coercive educational climate that predominated following America’s entry in World War I and during the subsequent Red Scare. Though wartime demands for “100% Americanism” waned, the notion that schools must promote or even compel a specific ideal of patriotism has persisted. Look no further than the so-called “1776 Commission,” which, to the chagrin of countless historians, proposed revising K-12 history and civics curricula to privilege a celebratory and simplistic vision of American history. Though consistently framed as a means of forging a sense of unity among the rising generation, patriotic education initiatives—in both the Progressive Era and our own time—have aimed to standardize a narrow vision of what it means to be an American.

By 1907, in line with Nelson’s proclamation, the course of study for Salt Lake City schools suggested that students receive intensive training in patriotism beginning in the third grade. When they reached the fourth and fifth grade, the city’s schoolchildren would be instructed to “honor and revere the flag as the symbol of national honor, integrity and greatness.”[3] Although these initiatives largely served to placate adults, they placed very real demands on students. All freshmen and sophomore boys in the state, for instance, were required to participate in daily military drills. While prominent educators on the national level objected to the physical toll soldiering exerted on developing boys, not to mention its militaristic implications, most viewed daily patriotic exercises as benign.

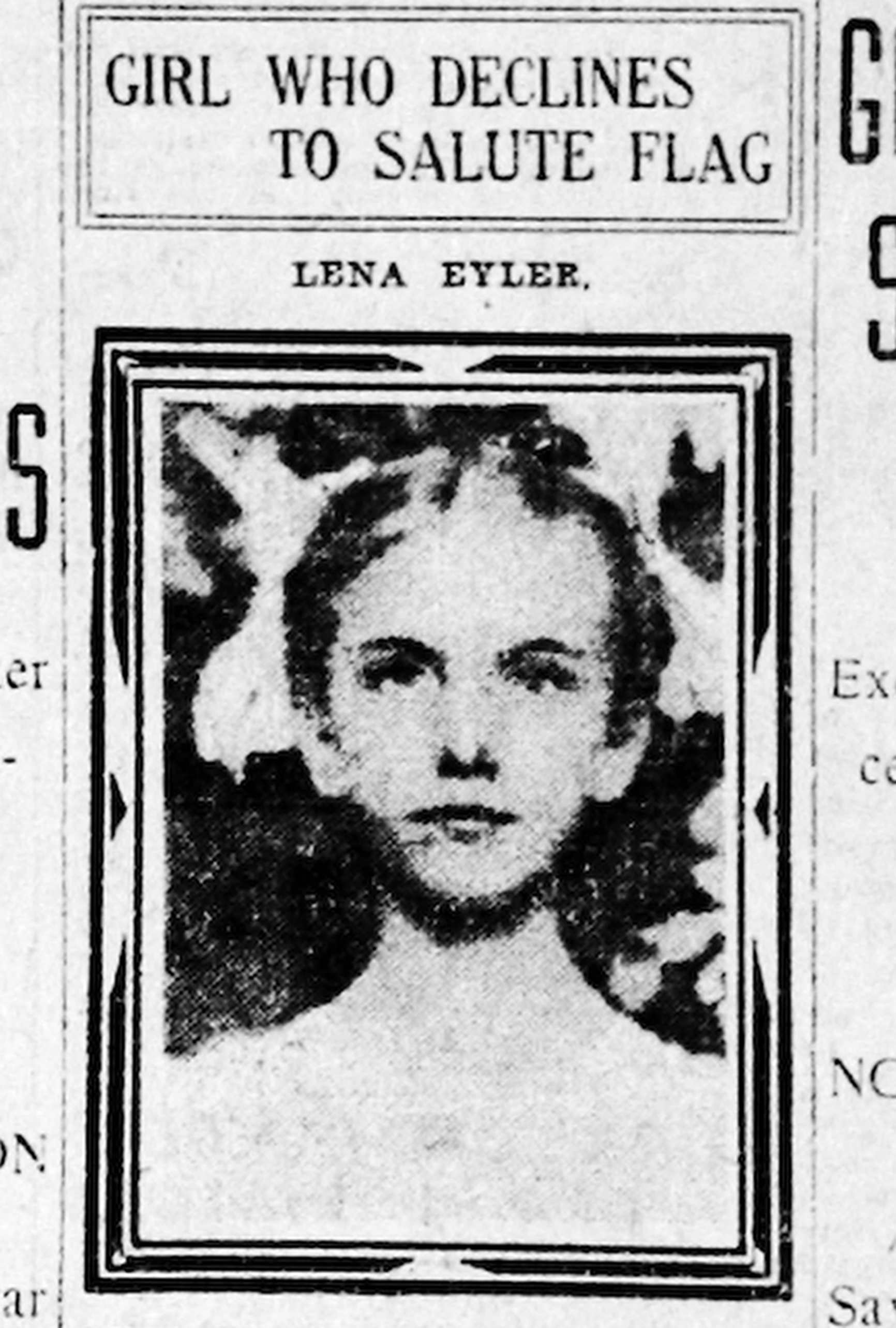

In 1912, Lena Eyler, a thirteen-year-old student at Salt Lake’s Franklin School, challenged these assumptions when she refused to salute the American flag during a recitation of the “Pledge of Allegiance.” In response, D. H. Christensen, the city superintendent, expelled her. Eyler’s protest was a planned political statement, not a spontaneous outburst. As she explained her action: “I will not salute that flag . . . if I must salute a flag it will be the red flag of Socialism because I think it stands more for liberty and justice than the Stars and Stripes.” The school’s principal, who described Eyler as bright and precocious, nonetheless supported her expulsion, as he worried that the girl’s protest would “counteract our efforts to teach to other students patriotism, love of country and good citizenship.” Christensen suggested Eyler could return to school if she agreed to salute, but the young student refused, reiterating that the American flag did not represent her values. [4] The Salt Lake Tribune claimed that Eyler’s convictions owed to the influence of her stepfather John G. Dunn, a Scottish immigrant who was “prominent in local Socialist circles.”[5]

The decision received national attention. Socialists in Utah and across the country offered Eyler support. The Daily People, a newspaper produced by the New York-based Socialist Labor Party, compared Eyler’s “deliberately intense and intensely deliberate” protest to those of the “early Christian martyrs.”[6] A Socialist Party branch in Salt Lake City even considered nominating its own candidates for the school board following the expulsion. Socialists had carved out a limited but noteworthy place in Utah’s political culture by the early twentieth century, with dozens winning elective office throughout the state, a pattern that reflected a national trend. In fact, just three days after Eyler’s protest made local news, Socialist Party candidate Eugene V. Debs garnered 6 percent of the national popular vote in the 1912 presidential election. Debs fared even better in Salt Lake County, earning 10 percent of the vote.

Despite its growing popularity, many self-proclaimed patriots—often allies of big business or anti-immigrant crusaders—contended that socialism was inherently un-American. Key figures in Utah, perhaps aiming to assuage those who doubted the state’s Americanism, came to share these sentiments. Tellingly, Eyler’s protest came shortly after the LDS Church launched a concerted effort to marginalize Utah’s socialists. In 1911, church president Joseph F. Smith, a nephew of founder Joseph Smith, directed Salt Lake City’s Deseret News to attack socialism whenever possible. A slew of other church publications also contributed to the effort. For instance, Improvement Era, a magazine published by the church, claimed the Eyler story merely highlighted the “commendable custom among the grades in the Salt Lake schools to salute the American flag,” and suggested that both Mormons and gentiles cheered Eyler’s expulsion.[7] (Ironically, that very custom owed to the efforts of a Christian socialist, Francis Bellamy, who penned the “Pledge of Allegiance” in 1892.)

Some members of Salt Lake City’s board of education expressed concern over the decision, questioning whether patriotism should be compulsory. Like many states around the turn of the twentieth century, Utah passed a law requiring that schools fly the American flag in 1905 but set no guidelines for saluting the flag or otherwise declaring loyalty to the nation. One board member argued against compulsion, noting, “We love to salute the flag because of the freedom it insures [sic] us, but I would fight any flag that sought to compel me to salute it.” Another disagreed, declaring that when “the child strays from the path of loyalty he should be brought back into the path by force if necessary.” In the end, the board decided against adopting a measure compelling students’ loyalty but affirmed that patriotism should be “one of the cardinal things taught in the school.” Christensen, however, noted the city still had the authority to dismiss students who refused to salute the flag. A “disloyal child,” he argued, should be treated the same as a “dishonest child.”[8]

It is unclear what happened to Eyler and her family after her expulsion. The example of her dissent, however, lived on in anti-socialist literature. Bolshevism: Its Cure, a 1919 polemic by former socialists turned conservative Catholics David Goldstein and Martha Moore Avery, used the Eyler incident as proof of the “evil effect of Red Flag propaganda” and to warn that socialism would make “all education Godless.”[9] Similarly, the recent “1776 Report” insists that socialism will lead Americans down a “dangerous path” and that religious faith is the “key to good character as well as good citizenship.” Not coincidentally, this report comes at a time when increasing numbers of young Americans view socialism favorably. The notion that the public schools should instill loyalty and a reverence for tradition rather than encourage critical thinking, one that Salt Lake City’s school officials cosigned when they expelled Lena Eyler over a century ago, has proven surprisingly, and unfortunately, resilient.

Dr. Cody Dodge Ewert

Cody Dodge Ewert is an editor and historian currently based in South Dakota. He received a PhD in history from New York University in 2018 after earning his BA and MA degrees from the University of Montana. His research has appeared in the Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era and Montana: The Magazine of Western History, among other outlets. His first book, which examines how nationalism informed school reform campaigns during the Progressive Era, is forthcoming from Johns Hopkins University Press.