By William J. Hansard

February 19, 2019

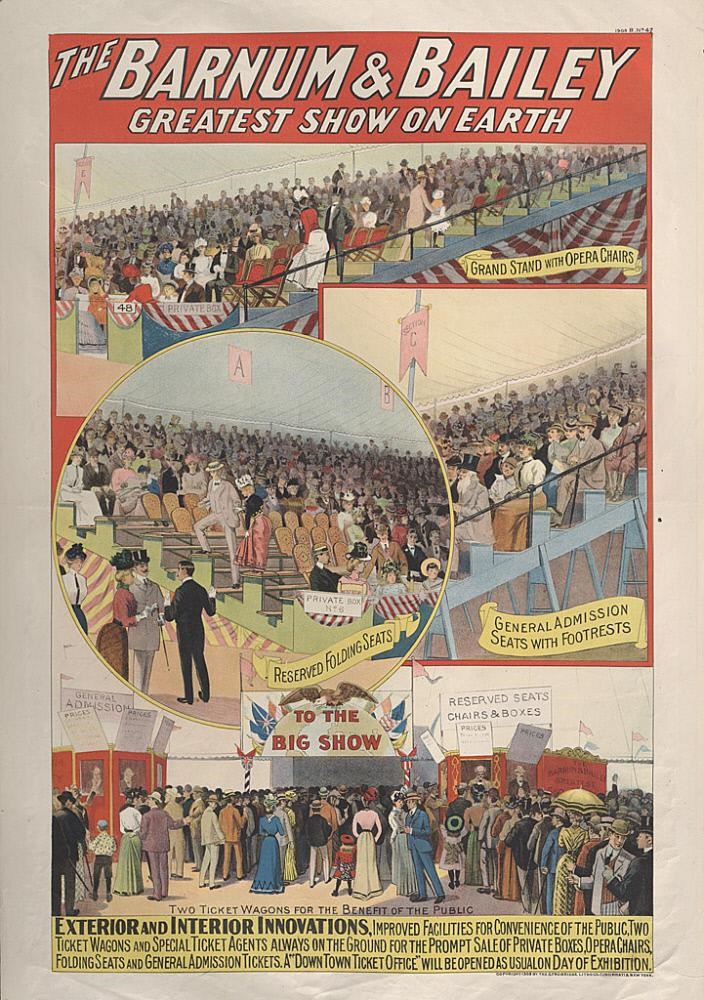

In the 1903 circus season, the Barnum & Bailey circus had just returned to the United States from a five-year tour of Europe. Although the effects of the show’s absence on its brand were minimal, proprietor James A. Bailey still felt the need to make sure the show was more extravagant than ever before. Not just the performances, but all aspects of the traveling show needed to be more spectacular and indulgent. Perhaps the most interesting change he implemented was to replace much of the seating in the big top with heavy iron opera chairs—with footrests—that he had brought back from Europe.

At every turn, the traveling circus in the United States was an exercise in hyperbole and spectacle; the Barnum & Bailey circus did, after all, refer to itself as the “Greatest Show on Earth!” To Americans, spectacle and power were nearly synonymous, and the circus was an incomparable experience and a force to be reckoned with. The circus, through methods sometimes as simple as using opera chairs, came to serve as a symbol of the United States’ industrial prowess and ever-growing significance on the world stage.

Beyond the performances themselves, the circus was comprised of multiple forms of spectacle. These performances interacted with several other elements of American history, such as mass culture, the nation-state, and industrialization to indelibly inscribe its power upon the American landscape.

Before the arrival of a circus to a town, an advance team known as the “opposition gang” brought its own form of spectacle. The job of the opposition gang was to claim the town in the name of the circus they represented. These teams plastered towns with thousands of posters, offering free tickets to building owners in exchange for advertising space. “Circus billposters marked the landscape, claimed it, and transformed it months before the actual onslaught of crowds, tents, and animals,” historian Janet Davis argues.[1]

During the 1903 season—which a handful of reporters around the country referred to as the “Great Circus War”—the people of Rockford, Illinois, found themselves annoyed by the intrusive billing. “The bill posters have made Rockford look like a veritable bedlam,” a reporter for the Rockford Morning Star grumbled.[2] A reporter for that city’s Daily Republic noted sarcastically that the billposters had missed the veteran’s memorial hall, which was soon to be dedicated by the President of the United States. He mockingly suggested that the billposters ought to “get the stand built from which President Roosevelt is to speak to the multitudes June 3 and let the circus men decorate that with flaring posters and gay bunting, on which is printed truths about the greatest show on earth.”[3] Thus, even before the canvas city had been erected, the circus had already physically inscribed itself onto the landscape.

These billing wars could be especially advantageous for second-tier shows. As D.F. Lynch, who was in charge of advertising for the Wallace Brothers circus, told a reporter for the Rockford Morning Star: “It draws a larger crowd, though not in proportion to the additional expense. But the fact that a circus comes out ahead … is worth much in the next stand as an advertisement.”[4] He goes on to note that the smaller circuses also benefited from the popularity of Barnum & Bailey and Ringling Brothers. Thousands were turned away when shows reached capacity and were eager to see the next circus that arrived.[5] It was not only the biggest shows that claimed the landscape for their brand, but the entire circus industry, regardless of who was on top at any given moment.

Once the circus arrived, the labor required to mount the circus became part of the show. Crowds gathered before the dawn to watch the workmen unload the train and raise the tents. The crowds did not disperse until after the circus had been dismantled. The famously rhythmic “Bailey method” of driving stakes was even immortalized in Disney’s Dumbo! However, labor spectacles could both contribute to and challenge the circus’s ability to project power. Strikes by the canvasmen on the Barnum and Bailey Circus in 1903 led to its inability to move every day, and some feared the strike might extend to the performers:

What care we for the subway strike,

Or for the “L” train crews?

But woe is ours if to freak

The circus freaks refuse.

What, ho! ye walking delegate,

In whom all evils Lurk,

Come forth and face the populace.

Is this your ghastly work? [6]

That the poem joked about being more concerned about circus labor than the construction of the subway speaks to the powerful nature of the circus in American culture. The second half of the poem is revealing as well, in that it suggests that the strike was instigated by a labor organizer, rather than being an authentic form of resistance by the underpaid and overworked canvasmen.

It was not only explicitly performative acts which provided the spectacle for the circus; the physical presence of what historian LeRoy Ashby analyzed as “a traveling company town” also served to demonstrate its power.[7]

For example, the circus had the ability to draw and hold entire populations. As Davis argues, “The mammoth circus audience was also part of the spectacle, as thousands of strangers from around a county streamed into town. Newspapers focused on the crowd as a defining element of Circus Day.”[8]

Circuses were also spectacular in their mobility, moving each day roughly 1,200 employees, hundreds of animals, supplies, etc. So logistically efficient was the circus that military forces studied their organization and operation. While the Ringling circus was in Visalia, California, in 1903, officers of the U.S. Cavalry studied the show and were impressed by the horses’ training. “We train our horses to lie down but our method is crude compared with yours,” one captain said.[9]

The circus could be just as powerful when it was stationary. In 1903, the Ringling circus opened with a sixteen-day engagement at the Coliseum in Chicago. The spectacle was so large that it could not be contained within the venue. Nearly every spare house, barn, and hotel in the vicinity had to be rented out![10] Through the physical footprint of the show, the circus laid claim to the activity of the city far beyond the confines of the venue. In San Francisco, the show was exhibited on a lot which was barely large enough to place the big top and the menagerie. The stakes had to be driven in private residences, with lines run through holes cut in the fences! Other facilities were placed wherever space could be found, including in a shed behind an orphan asylum. In this case, the circus quite literally made its mark on the landscape through physical alterations.

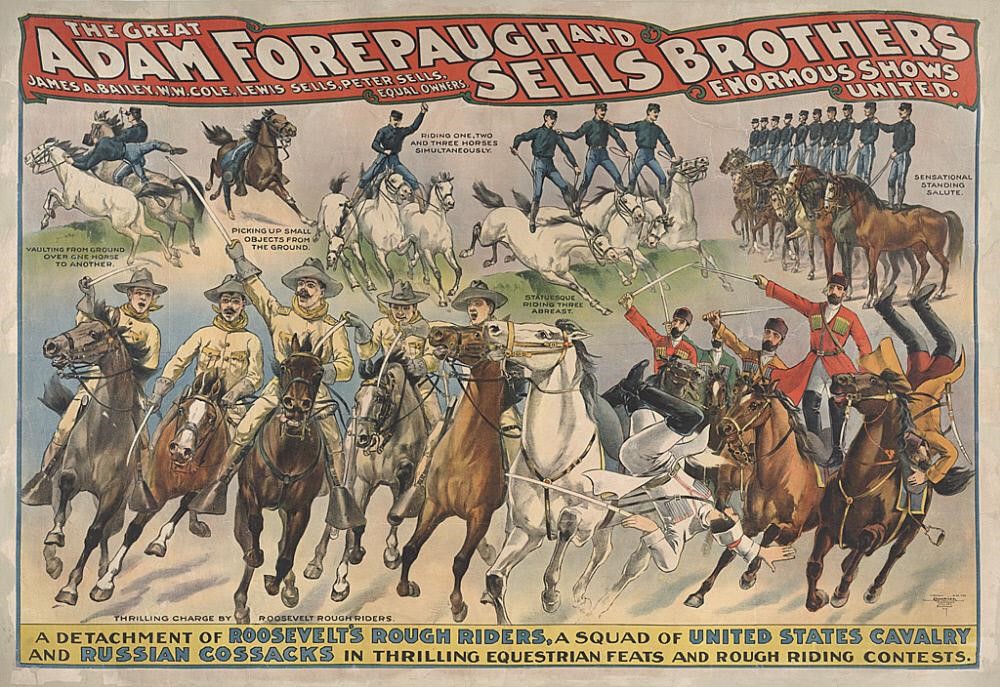

These spectacles of the circus were so powerful that the circus became a lens through which Americans saw the world. American imperialism both influenced and was influenced by circus imagery. One particularly interesting example takes this argument full-circle. In 1898, Theodore Roosevelt’s volunteer cavalry regiment named themselves the “Rough Riders” after

William F. Cody’s traveling show, which in 1893 had been expanded to Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and Congress of Rough Riders of the World. Soon after the famous charge up San Juan Hill, imagery of this and other scenes from the Spanish-American War became commonplace. The first circus routine based on Roosevelt’s Rough Riders, for example, was performed at the Ringling Brothers show in 1889, less than a year after the Battle of San Juan Hill. Because this imagery was so prevalent, Americans tended to understand imperialism through circus imagery. As Ashby notes:

Territorial expansion fused neatly with entertainment. Indeed, in 1901, one reporter believed that the war against Filipino rebels resembled a Wild West show: “The Theory of the Administration is that the trouble in the Philippines is like the Wild West show. It isn’t war, but it looks a good deal like it.”[11]

Ultimately, it was through spectacles such as these that the circus burrowed itself into the American consciousness, to the point that everyday language became peppered with references to it, Americans speak of bandwagons, dog and pony shows, safety nets, and more. It was this tendency toward spectacle in all things—even the seating—that made the circus the most important form of entertainment in turn-of-the-century America. Through billing wars, performative labor, logistical efficiency, and imperialist imagery, the circus indelibly inscribed its power on the American landscape—both metaphorically and literally.

William J. Hansard

William J. Hansard is a Ph.D. student in the Transatlantic History program at the University of Texas at Arlington. His research interests include history of popular culture, public history, and historical geography. His dissertation will explore labor in the traveling circus in the Gilded Age and Progressive Era.