by Beau Driver

March 5, 2019

Most historians have felt the thrill of discovery at some point while in the archives. There is a rush that comes with finding something new. For me, it has often felt as though I was suddenly taking an active role in the history that I study. I’ve experienced some of these moments in the archives when, for example, I realized that the second page of a letter that was listed as “missing” was actually in another collection that I had just been looking at. But in the summer of 2016, I made a discovery that for me was the fabled “mother lode” and laid out my dissertation before me.

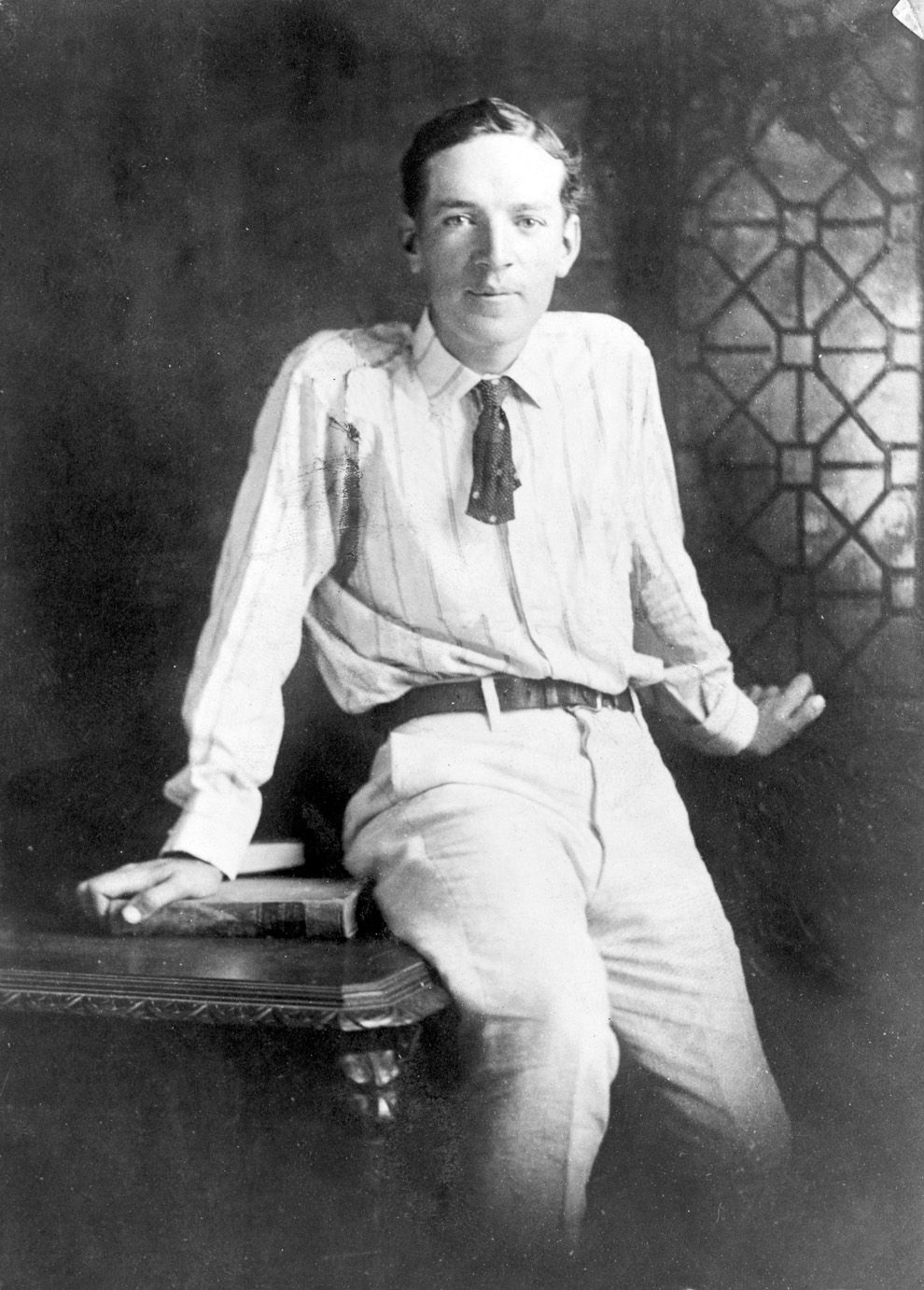

My research is on the Princeton sociologist Walter Augustus Wyckoff. Readers may recall that Wycoff gained a fair amount of fame at the turn of the 20th century through the publication of his two-volume investigation, The Workers: The East and The Workers: The West (1897, 1898). My dissertation traces the connections between Wyckoff’s work and that of authors like Stephen Crane, Jack London, and Upton Sinclair. It is also the first biography of Wyckoff. I show that Wyckoff’s motivation to investigate the working class came from the influence of his “Third-Culture Kid” (TCK) upbringing, as the son of missionaries in India. TCKs have a tendency to identify with numerous cultures easily because their own cultural identity is not well-defined due to having lived outside of their “home culture.”[1] Wyckoff was a middle-class man who had travelled extensively and had worked as a personal tutor to George Morgan, nephew of the great industrialist, J.P. Morgan, and younger brother of Wyckoff’s good friend, Junius Spencer Morgan II. Yet, his life abroad—combined with his experiences with the very wealthy and the very poor—gave him the tools he needed to cross cultural boundaries and the empathy that allowed him to identify with his subjects. In The Workers, Wyckoff details how he made his way across the United States by working odd jobs as an unskilled laborer. His goal was to find “a place among original investigators” of class. The journey across the continent was recommended to him by a Colorado mining executive. Feeling that his understanding of the working class was far too academic, Wycoff immediately made plans to embark upon his “experiment in reality.”

Wyckoff left his middle-class world in June of 1891 when he began to walk across the United States. He eventually made his way from Connecticut to California. During his “tramp” across country, Wyckoff passed through lumber camps in Pennsylvania and vast farmlands in the Midwest. He worked in the industrial world of Chicago’s factories, on the crews at the site of the 1893 Columbian Exposition. He observed mining camps of Colorado and finally reached the Pacific in early 1893. Wyckoff then turned his notes on his travels into The Workers, which brought him fame as an investigator of class and connected him to people like Theodore Roosevelt, Henry James, and Hamlin Garland.

My own journey was a reverse of Wyckoff’s, albeit fueled by gasoline and the internal-combustion engine. It had taken me much less time, but I was just as interested in getting to the root of an issue. The trip in the summer of 2016 was my second journey to do research at the Seeley Mudd and Firestone libraries at Princeton. I aimed to get to the bottom of Wyckoff’s life and more fully understand what would cause a well-educated Princetonian to spend eighteen months among laborers. Wyckoff’s work would make him the most famous of these undercover investigators of class during his lifetime, and I was fascinated by the fact that unlike most of the investigators and journalists that had examined the lower classes before him, Wyckoff specifically tried to live and act like his subjects, the workers. He dressed as a worker and performed his own working-class identity.[2] He also found himself constantly preoccupied by his own masculinity and the fact that his middle-class life did not prepare him to work with the sturdy workmen that he encountered. Wyckoff’s dilemma fascinated me. I felt as though I had been, for the last few years, performing my own version of Wyckoff’s experiment, again in reverse. For my part, I had come to the University of Colorado as a 32-year old from a working-class family and had only just finished my BA in history. I felt very much out of place in the halls of academia, likely in the same ways that Wyckoff felt during his attempts to cut lumber or work demolition. And so, I found myself, a sort of mirror image of Wyckoff, in New Jersey at an Ivy League university.

Princeton University Archives.

However, the discovery I made was not among the stunning collections of Princeton but at the more modest archives at Lafayette College in Easton, Pennsylvania. A short article written about Wyckoff in the early 1960s mentioned, in a footnote, that Professor Alfred E. Pierce of Lafayette College was writing the definitive biography of Wyckoff. A professor of economics at Lafayette, Pierce had become fascinated by Wyckoff as a young man after reading The Workers. When he settled at Lafayette, he began to research Wyckoff in an attempt to bring back some of the fame that Wyckoff experienced in his day. I had no idea how far Pierce had gotten in his efforts or if there would be any trace of his Wyckoff project.

When I got to my hotel in New Jersey, I called the archives at Lafayette to ask if they had any papers from Pierce. It was a long shot. I had spent some time looking at their holdings online and had not seen anything of interest. The archivist on the line asked me to hold, saying that she thought she had seen a box somewhere. The next ten minutes were tense as I waited to hear if there was anything. She came back saying, “There’s just one file box here. It has some folders and it’s all about someone named ‘Wyckoff.’” My reply: “I’ll be there tomorrow.”

In the single box that Pierce left to Lafayette was a treasure trove of material for me. Pierce had begun working on his biography of Wyckoff in 1956, when he had written to the American Wyckoff Association, a genealogical group of the Wyckoff family, for info. A few years later, Pierce came into contact with Walter Wyckoff’s only child, Constance Wyckoff, and through Constance, he met Leah Wyckoff, Walter’s widow.

The problem with researching Walter Wyckoff is that he left very few papers. Wyckoff died in 1908, at the age of 43. I surmise in my dissertation that this early passing was a significant part of why he is not better remembered today, as was the fact that he did not fit neatly into any single discipline during his lifetime. Had he continued to be a productive scholar for another twenty or so years, he might very likely would have solidified his place among other influential social scientists like Frank Lester Ward, Richard T. Ely, and Charles A. Beard. Further, because of his passing at a young age, and because he had only been teaching at Princeton for twelve years, the board at Princeton deemed that he had not been there long enough to warrant a pension for his widow and daughter. It also may be that Leah Wyckoff’s Jewish background influenced the decision of the president of Princeton, Woodrow Wilson, not to grant her a pension. Justifiably upset by this, Leah Wyckoff did not have an interest in making sure that Wyckoff’s papers were given to the university. When Pierce contacted Constance, she had only a small number of her father’s papers, none of which were left in the collection of Pierce at Lafayette. However, Pierce had taken fastidious notes of interviews and conversations that he had with Constance and Leah—along with other family members and a few students of Wyckoff’s—and listed all of the items that Constance sent to him for his research.

Pierce used these interviews along with the few papers that Wyckoff’s family still had to construct a biography of the man. Unfortunately for Pierce, no publisher that he reached out to had an interest in publishing his manuscript. Around 1970, Pierce shelved the project and apparently never returned to it. When he died in 2008, he left his box of material to Lafayette, no doubt hoping that someone would come along and pick up the project. And here I was, sixty years after Pierce started his biography.

Even with Pierce’s papers, there is scant information to use. Wyckoff published during his most productive years, but they were cut short. Pierce’s box of material holds a few great insights, but it also holds frustration and tantalizing evidence that is lost to me. For instance, Leah Wyckoff wrote an autobiography, A Wonderful Life’s Ups and Downs, which Pierce read and made notes about. But the manuscript was returned to Leah, and all that I have are a few of Pierce’s notes on its contents. Twenty years later, Pierce, no doubt, would have had access to a Xerox machine to photocopy these materials. Alas, they are gone.

One other thing that remains is a note from Upton Sinclair. It was this discovery that brought on such a rush of excitement that I had to go outside into the summer afternoon for a moment to collect myself. On September 20, 1963, the Lilly Library at Indiana University opened an exhibit of “books, manuscripts and other materials” from the Upton Sinclair Archives. In the Alfred E. Pierce papers at Lafayette College, there is a program from this event. It notes that Indiana University opened this exhibit to mark the occasion on Upton Sinclair’s eighty-fifth birthday. On the back of Pierce’s copy, one finds this handwritten note:

Dear Mr. Pierce,

Yes, I read Wyckoff’s book when it appeared and it taught me a lot.

Sincerely,

Upton Sinclair

While many readers of this blog are not likely to be familiar with Wyckoff, it seems to me that nearly all of them will know Mr. Sinclair. This one small note has helped me to connect Wyckoff’s work to that of similar writers during the Progressive Era. It has opened my dissertation up in ways that I did not expect. Further, these connections to “muckrakers” like Sinclair helps to place Wyckoff’s work in the context of the next generation of writers who sought to understand the lives and labors of American workers at the turn of the twentieth century.

Beau Driver

Beau Driver is a Ph.D. Candidate at the University of Colorado, Boulder, where he will defend his dissertation, "The Worker: Walter Wyckoff and His Experiment in Reality," this spring. Beau is also a co-founder of Erstwhile Blog, a blog created and managed by history graduate students from CU.