By Jessica Brabble, Dr. Ariel Ludwig, and Dr. E. Thomas Ewing

August 11, 2020

This post is part of a series exploring the lived experience of Americans during the 1918 influenza pandemic. Read the other posts in the series here.

Influenza Masks in Stockton

On November 15, 1918, in the midst of the influenza epidemic, C. E. Stanford, a resident of Stockton, California, openly defied the city’s mask ordinance saying, “I have never worn an influenza mask and never will. I am a healthy man now and know full well if I put one of those things on, I will get sick. I would rather stay in jail the rest of my life than wear one.”[1]

An extended account of Stanford’s defiance provides insights into the tensions between enforcing, contesting, and evading mask ordinances. After proclaiming “that [he] had never worn a mask, was not wearing one, and would never wear one,” Stanford was “gathered in by the alert police force and forthwith confined in the county jail,” where he spent the night. The next morning, Stanford’s fifteen-year-old son came to the jail “and pleaded that his father be released, saying that he had bought masks for his father at different times but he refused to wear them.” Told that $25 bail would bring his release, “Stanford flatly refused…and the boy left the jail crying.” Later that day, however, Stanford “changed his mind.” Appearing before Justice Parker, “incidentally wearing a mask of generous proportions,” he declared his “intention of following out the letter of the law,” at which point he was released, “no formal charge having been made against him.”[2]

Stanford’s bold statement seems especially evocative in summer 2020, as the COVID-19 epidemic has forced the United States and the world to think about masks in three crucial ways: as a public health recommendation, an individual choice, and, increasingly, a legal requirement. The current situation has brought new attention to the in 1918-1919, particularly the most familiar example, San Francisco, which has been examined in historical accounts, document collections, and popular articles. This essay explores the example set by the city of Stockton, which makes for a powerful case study because the city council, the mayor, and the city health officer implemented the mask ordinance three times across the influenza epidemic from late October 1918 to early February 1919.

This essay examines two ways in which the mask ordinance involved forms of bodily control, personal choice, and public performance: first, the arrest of individuals defying the law, and second, the public parade celebrating the war’s end on November 11, 1918. Both arrests and celebrations demonstrate how local officials, including the government and the police, used the mask ordinance as a disciplinary tool that forced individuals to modify behaviors to meet legal requirements. Public arrests and celebrations illustrate how the mask mandate involved complicated performances. Individuals arrested for defying the mask ordinance found their transgressions displayed in public spaces, especially those whose names were published in the newspaper, regardless of whether their actions resulted from deliberate defiance or simple neglect. Photos of the November 1918 celebration show that some individuals displayed their adherence to the mandate while wearing masks, yet many others did not wear masks at the parade, which confirms that encouraging and requiring certain forms of behavior did not ensure uniformity in public performances. This historical analysis of ordinances, arrests, and celebrations in Stockton thus contributes to contemporary debates about the use of masks as forms of legal, individual, and community responses to COVID-19.

Mask Ordinances

From the middle of October 1918 through early February 1919, Stockton lived under a mask ordinance for seventy-three days, approximately 60 percent of the epidemic. During the first weeks of the epidemic in Stockton, the local health board initially recommended masks for nurses caring for influenza patients and then for occupations “coming into contact with the public,” such as bank employees, store clerks, and restaurant waiters.[3] On October 24, the city council passed an ordinance requiring masks for “every person appearing on the public streets,” in any place where “two or more persons are congregated” other than homes, and for anyone engaged in sale or distribution of food or clothing. Violating the ordinance could bring fines up to $150, imprisonment up to 150 days, or both.[4]

This first mask ordinance ended on November 28, Thanksgiving Day, when the newspaper announced, “Masks are Off and Joy Reigns.”[5] Just two weeks later, however, as the number of cases rose, an emergency ordinance “requiring all persons to wear the prescribed mask to safeguard against the spread of the influenza” went into effect on December 13.[6] After cases decreased, the city council repealed the second mask ordinance on December 23.[7]

On January 10, 1919, the city council imposed the mask ordinance for a third time, when the Mayor called for “decisive action.”[8] Toward the end of January, as cases declined, closing orders were lifted, but the mask ordinance remained in effect.[9] On February 7, the mask ordinance was again lifted, leading the Stockton Daily Evening Record to declare, “[O]nce more it is lawful to go about without the gauze face adornment.”[10]

Arrests for Mask Violations

The enforcement of the mask ordinance began on October 26, when three men were brought to Justice H. Tyre for “severe reprimands” for failing to wear masks. In the next few days, two more people were arrested, but the Record claimed that “the majority of the people are cheerfully following out the request of the board of health.”[11] The first case of open defiance occurred when R. F. Hollingshead, a laborer, allegedly “sassed” a police officer who questioned Hollingshead about the wearing of a mask under his chin, and then, “to make his argument still stronger, he pulled his mask off.” This exaggerated act of defiance confronted the policeman with a public performance that required a forceful response. Hollingshead was arrested, fined $10, lectured by Justice Tye, and “much chastened, he promised to behave himself in the future.” On October 29, the Record published the names of fourteen people arrested for mask violations.[12] On November 15, Stanford issued his defiant statement cited above.[13] On November 19, three men were fined $5 when they “showed their faces on a public street.”[14] As of November 23, police officers had “brought 232 offenders to court,” for an average of eight arrests per day.[15] Although the newspaper did not provide detailed reports by race, a report on November 2 that “nine Japanese” were arrested and another report on January 14 stating that “offenders were mostly Mexican” certainly suggests that minority and marginal populations may have been more vulnerable to arrest.[16]

During the ten days of the second mask ordinance, however, no arrests were reported in the newspaper. On December 18, four days after implementation, the Record conceded that many people “on the streets are seen without masks, and no arrests are reported.”[17] At the city council meeting on December 23, Commissioner Smith of the Department of Health and Safety admitted that the law was not being enforced: “But the people are not in back of the ordinance and it is simply impossible to enforce it. Why, I could order the police to start arresting on the streets this afternoon and they would arrest 99 of 100 persons.” Health Officer Dr. Minerva Goodman responded, “But why not try that? If you arrested 99, perhaps we could enforce the ordinance.” Both officials agreed that the ordinance failed to change behavior, yet they disagreed about arrests as a tool to advance this goal.

In the two days following the initiation of the third ordinance, more than two hundred arrests were made, leading the newspaper to conclude, “[N]o one wants to be seen on the streets today in the downtown section who did not have the regulation mask over his or her face.”[18] One week later, the Record reported an increase in arrests for “mask violations,” “[p]eople again having begun to grow lax in their observing the masking ordinance.”[19] Chief of Police Simpson reported 909 arrests in January, the “greatest number of these, 433, were for violation of Ordinance 686, the mask ordinance.”[20] After 200 arrests were made in the first two days, the average for the rest of the month was twelve per day, much higher than during the first mask ordinance. These rates of arrest point to the underlying logic that assumes arrest will compel behavior change, yet this tool was used inconsistently, unevenly, and with limited success. Although this record of arrests demonstrates the willingness of Stockton city officials to enforce the law, this record does not provide any evidence that the law itself resulted in any meaningful containment of the epidemic’s spread in the community. The mask ordinance thus functioned more as a tool to change how people appeared on the streets than it served as an effective public health measure.

Celebrating the End of War

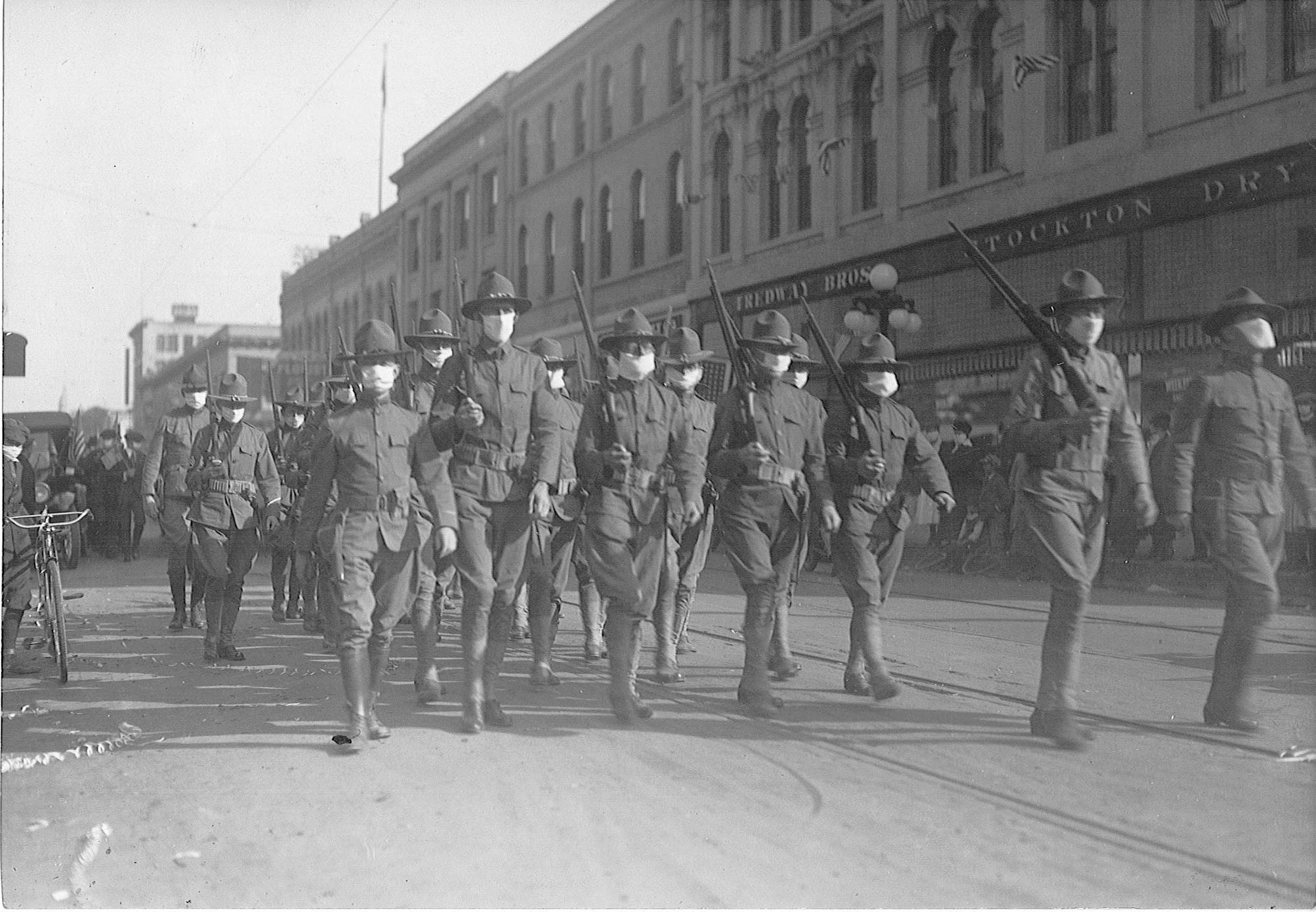

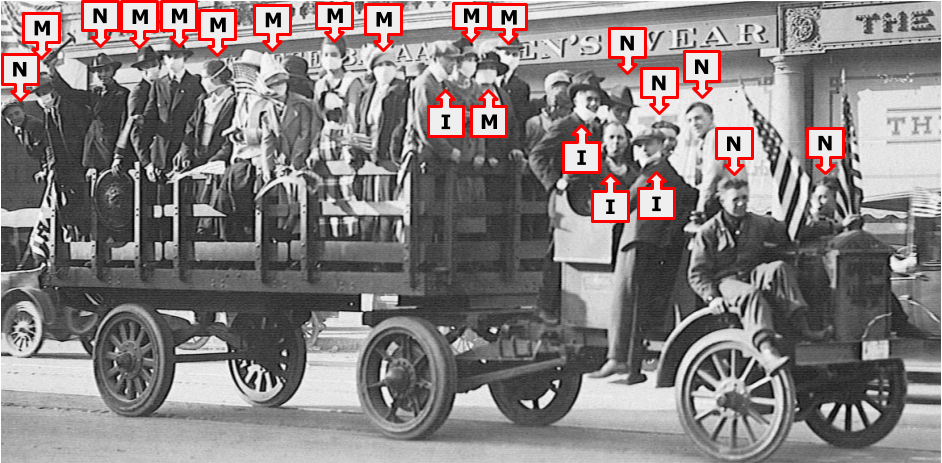

As the war neared an end, Stockton looked forward to a “monster parade as soon as armistice news is received,” but this anticipation was tempered by the Record, which cautioned, “The mask law will be rigidly enforced, and the police will take into custody any person who violates the ruling.”[21] Photographs taken on November 11 and preserved in the University of the Pacific library provide evidence of how masks were worn under the ordinance. To count mask wearers, we selected seven photographs of bystanders as well as soldiers, nurses, and citizens marching in the parade t. We classified each person as (M) Mask Worn Over Nose and Mouth; (N) No Mask Worn; (I) Mask Worn Incorrectly (I); (U) Unable to Identify Mask; or (P) Mask Possibly Worn Incorrectly.

Our analysis excluded nurses and soldiers, who wore masks as part of their uniform. Of the 150 civilians, we estimate that approximately two-thirds (100) wore masks, and most wore them correctly, covering their nose and mouth. We calculated that 10% (15) wore masks incorrectly (I) and 12% (18) obviously did not wear masks (N). The faces of 13% (20) were obscured (U). In sum, we estimated that two-thirds wore masks correctly, but nearly one-quarter violated the ordinance by wearing masks incorrectly or not at all.

Our investigation of mask usage by gender suggests that women were more likely to wear masks correctly. Out of 70 women whose masks could be classified, 86% (60) wore masks, 7% (5) wore masks incorrectly, and 7% (5) were not wearing masks. By comparison, out of 110 men, 72% (80) were wearing masks, 14% (15) wore masks incorrectly, and 14% (15) were not wearing masks. Even though a sizable majority of both genders wore masks, the share not wearing masks or wearing them incorrectly was twice as high for men (28%) as women (14%). The evidence suggesting that women were more likely to wear masks and to wear them correctly is suggestive of recent commentary in 2020 about the apparent reluctance of men to wear masks, which has prompted new efforts to emphasize the masculinity of mask wearing in response to COVID-19.

Learning Lessons for 2020

On June 9, 2020, the Stockton City Council rejected a proposal from Mayor Michael Tubbs to require masks in public in response to COVID-19. Echoing the grim predictions made a century earlier by his predecessors in city government, Tubbs warned: “If we don’t get a handle on this and start to bend the curve again, the state could come back and tell us to go back to shelter in place.” His proposal was not supported by any of the six other city council members, despite the rapid rise in cases. In fact, even after Stockton’s Sheriff tested positive for COVID-19, he announced that his office would not be enforcing Governor Gavin Newsom’s requirement to wear masks in public, even with a fine. The arguments for and against masks in 1918-1919 and 2020 have key similarities, including disputes about the government’s authority to regulate personal choices, the challenge of mandating specific forms of public behavior, questions about the effectiveness of masks in preventing infectious disease, and concerns by physicians, city leaders, and the public about mask refusal threatening community health. Now, as it was then, the politics of masking remain complicated, as public health officials try to find the right balance between recommending responsible practices and compelling radical changes in personal conduct. Dr. Maggie Park, San Joaquin County Health Officer, stated that social distancing, hand washing, and disinfecting frequently used items “are the most important steps to stop the spread of coronavirus,” but her statement included this bolded concession: “It is not an order or required that you wear a face covering; it is voluntary.” In a now largely Republican county, masks have come to be associated with the state’s infringement upon autonomy, foregrounding the politics of public health.

This case study of Stockton during the 1918-1919 epidemic provides some cautionary tales for Americans facing COVID-19. First, while the evidence for the effectiveness of masks in preventing the spread of disease is complicated, incomplete, and inconsistent, the arguments made by city health officials a century ago and echoed now demand attention: masks contribute to containing the spread of disease when they are worn correctly, consistently, and constantly. Second, while arrests targeted individuals, whose lack of a mask may have resulted from indifference, ignorance, or opposition, as voiced by Stanford, history teaches us that masking is a community effort in which individuals choose to act for the good of all, despite the inconvenience or discomfort. Finally, Americans in 2020 must remember that masking isn’t totally new. We have faced the ravages of a pandemic before and we can learn from our past as we debate wearing masks in schools, shops, businesses, and celebrations of patriotic holidays.