By Dr. Einav Rabinovitch-Fox

May 12, 2022

Last Monday, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City returned to its “First Monday at May” tradition, or as it is commonly known: the Met Gala. Drawing media attention and fashionistas from around the world, the Gala is the annual fundraising event for the museum’s Costume Institute. What began as a modest dinner held outside of the museum in 1948, has turned in recent years into a mega publicity event that brings to the museum millions of dollars in donations.

The Met Gala is perhaps the most important fashion event of the year, one that combines popular culture, money, and design. Usually themed around the topic of the annual costume exhibit, the night revolved around “Gilded Glamour,” as the museum celebrated “In America: An Anthology of Fashion,” the second portion of a two-part exhibition that explores fashion in the United States.

While the exhibition, located in and inspired by the Museum’s American Wing period rooms, featured clothing from the seventeenth century to the present, the Gala, as the theme indicated, centered around the Gilded Age. The choice to celebrate American design by focusing on a period in which French fashion was the criteria for good taste and a status symbol might seem odd at first glance. Certainly, as the exhibition itself shows, there are better periods that embody the idea of “American Fashion.”

Yet it seems that the decision to focus on the Gilded Age was less because of the period’s sartorial connection to America than the museum’s hope to harness the popularity of TV shows such as Yellowstone, 1883, and of course The Gilded Age, HBO’s newest hit, that center the period.

And like the shows, the museum chose only to highlight a narrow vision of the Gilded Age—that of the “Gilded Glamour.” Despite being a period of increasing class divisions, rampant racial violence, brutal industrialization, and the exploitation of immigrants and women, the Gilded Age that the Met Museum celebrated revolved around fancy dresses and opulence, or what Thorstein Veblen defined as “conspicuous consumption.”

This interpretation of the Gilded Age is not that surprising coming from the Met. After all, the idea of an over-the-top costume party attended by the richest few is no stranger to Gilded Age culture. Although the extravagance of the Gala is a relatively new phenomenon in the event’s history, this is not the first time the city has seen such an event.

Back in 1883, New York elite gathered at one of the city’s grand mansions for an elaborate costume ball that fused together, like the modern Gala, fashion, wealth, and performance. The ball, organized by Alva Vanderbilt, the wife of railroad magnate William K. Vanderbilt, served both as a housewarming party and, and most importantly, as a way to claim the Vanderbilts’ prominence among the New York elite. Drawing media buzz and public attention, the ball symbolized the shifting power from “Old Money” New York, represented by Mrs. Astor and her “400 list,” to “New Money,” represented by the Vanderbilts and their conspicuous exhibition of wealth.

The ball, which was covered heavily by the New York Times, included five choreographed quadrille dances and an elaborate dinner served by the chefs of Delmonico’s—one of the most prestigious institutions of the time. The 1200 guests, all from the highest social ranks, arrived in costumes, even the reluctant Mrs. Astor. Among the more ostentatious dresses were Mrs. Cornelius Vanderbilt II’s “Electric Light” dress, which had a torch that lit up, and Miss Kate Fearing Strong’s outfit, which paid homage to her nickname “puss” and included a taxidermied cat head as a hat and seven cat tails sewn onto the skirt.

The outrageously Vanderbilt ball, with an estimated cost of $250,000 (around 6 million today), symbolized the detachment of these rich elites from the growing suffering of the poor and the insurmountable gaps in wealth of that period that would eventually lead to social unrest. In a sense, it was the ball, and others like it, that epitomized the “Gilded” nature of the Gilded Age, a term coined by Mark Twain in 1873 to point to the greed and corruption that defined the era which was far less golden than it seemed.

The Met Gala, with ticket prices running from $30,000 for a single seat and up to $250,000 per table, can be seen as a modern incarnation of these balls. Like them, it relies on exclusivity and affluence. Unlike popular award shows like the Oscars or the Grammys, the Met Gala rewards nothing and instead serves as the ultimate opportunity to see and be seen by an elite milieu, solidifying its status while simultaneously demonstrating its aloofness. Gathering donations for one of the richest museums in the world, the Gala is not about bettering society through philanthropy but about maintaining the power structure that created the museum as a refuge for the wealthy.

Just like the crowds who gathered in 1883 to get a glimpse at the rich in their costumes, the masses today also function as outside viewers, who get a tease of another world but never an invitation to step in. The only broadcasted part of the event is the red carpet, where guests have the chance to show their outfits, but the inner workings of the party remain a secret, privy only to the selected few, which intensifies even more the exclusivity of the event.

And it seemed that this invisible barrier between the world of the wealthy and the rest of us, the one that the Gilded Age was so successful in crafting, was what became most evident at the Gala, not a celebration of fashion. Contrary to predictions that the event would be a tribute to the period’s styles of luxurious corseted ball gowns, puffy sleeves, and elaborate bustles, guests brought their own versions of gilt that did not always correspond to historical accuracy.

Indeed, the interpretation of the period’s styles was overall lacking. Despite many examples for Gilded Age fashions, some of them—like the famous John Singer Sargent’s Madame X—literally hanging on the Met walls, most guests decided to concentrate on the “Glamour” side of the theme, featuring dresses inspired more by the 1920s, 1940s, and Art Deco than the Gilded Age. Even actress Christine Baranski who plays the “old money” matron Agnes Von Rhijn in HBO’s The Gilded Age decided to abandon her period dresses in favor of a modern suit.

Only a few Gala guests, among them singers Billie Eilish and Lizzo, as well as actresses Nicola Coughlan and Blake Lively—who wore a copper dress that patinated on the red carpet as a tribute to the Statue of Liberty—understood the assignment. Corsets were also a rare sight on the red carpet, and interestingly it was mainly men—such as Lenny Kravitz and Ben Platt—who donned the famous clothing item that defined the period’s styles. Those who hoped to see modern interpretations of the Gibson Girl however, the most marketable image of the 1890s, remained disappointed.

To be sure, the theme of the Gala changes from year to year, and sometimes guests do use the platform to make political statements (the previous Met Gala that celebrated the first installment of the exhibit “In America” contained multiple statements of political nature). However, for this Gala, guests seemed more comfortable to remain oblivious to the apparent disconnect this show of wealth presents in the midst of a pandemic, war, and soaring inflation. The actor Riz Ahmed was the sole exception, appearing dressed in work boots, blue silk overshirt, and a white undershirt, as an homage “to the immigrant workers who kept the Gilded Age going.” Other guests preferred to avoid any political controversy, even the one that was unfolding as the evening progressed with the news of the leaked SCOTUS opinion draft that overturns Roe v. Wade.

Yet this out-of-touch event that focused on glamorous fashion devoid of political meaning is just what made the Gala so in line with the Gilded Age: the celebration of celebrity and wealth, most notably the presence of billionaire Elon Musk who is maybe the closest modern incarnation of the robber baron, absent of any regard for the plea of laborers. No one on the red carpet, including Anna Wintour, Vogue’s chief editor, seemed to mind that Condé Nast, the publisher sponsoring the event, has still not recognized its employees’ union.

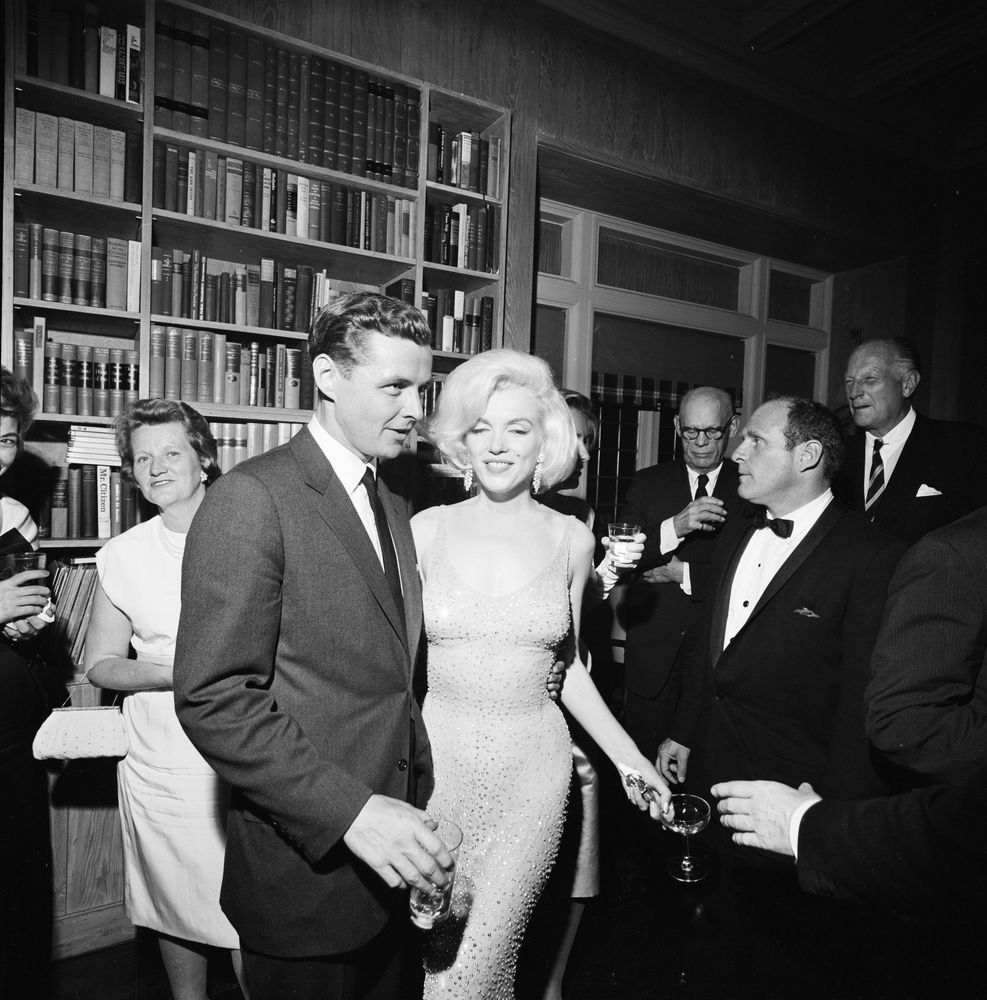

If we needed any more proof that we are in the midst of a “second Gilded Age,” Kim Kardashian, wearing the original Marilyn Monroe’s Happy Birthday Mr. President nude dress, provided it. Kardashian, who made her fame and fortune off of reality TV, and who was once ridiculed and shunned from exclusive events like the Gala, was the last guest to arrive to get the full media attention. Kardashian hoped to send a message of power to the more established elite, but in the process she created a fashion controversy that simultaneously channeled history and showed disrespect to it, underlining the true nature of the evening.

Yet, as much as the politics of the Met Gala were similar to those of the Gilded Age, Kardashian is not the Alva Vanderbilt of a century ago. While Vanderbilt was, too, a scandalous woman who was not afraid to challenge societal norms while creating new ones, she used her power and influence not only to promote her brand. Yes, the balls of the Gilded Age were maybe ostentatious, but they were also very much political. These balls served as a way for women like Vanderbilt to claim their place in what was and still is a man’s world. They allowed her to form networks and assert power, which she later channeled to her work in promoting women’s suffrage and other worthy causes.

Kardashian, Musk, and all the other guests could have used the Met Gala and its platform to advance multiple deserving causes, or even to start a conversation about the place of art and design in the modern world. They could have shown us that beyond the glamour there was accountability. But in the end, all that was left from all the glitter and the gilt, like Kardashian herself, was a pale copy of the original.

Dr. Einav Rabinovitch-Fox

Einav Rabinovitch-Fox teaches at Case Western Reserve University. Her research examines the intersections between culture, politics, and modernity. Her new book is Dressed for Freedom: The Fashionable Politics of American Feminism. She tweets @DrEinavRFox.