By Elizabeth D. Katz, Ph.D., J.D.

September 8, 2021

This is part of a series of blog posts on women’s history and the long Progressive Era, honoring the legacy of the late Elisabeth Israels Perry. Perry served as SHGAPE President from 1998-2000 and had a long and distinguished career that highlighted women’s political activism in GAPE and in the “long Progressive Era” that stretched into the 1920s and 1930s. This blog series coincides with the July issue of the Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era, which includes a roundtable (available to subscribers online) on Perry’s After the Vote: Feminist Politics in La Guardia’s New York (2019). Read the other posts in the series here and find the CFP here.

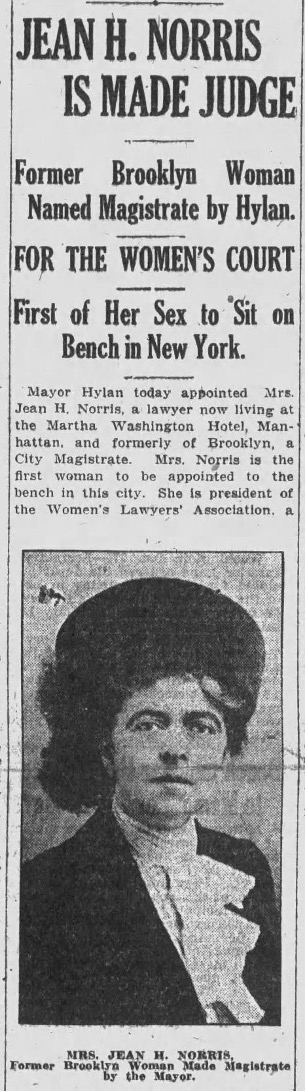

In 1919, two years after women secured suffrage in New York, a pair of the country’s most distinguished and prominent women lawyers sought positions in New York City’s judiciary. Only one succeeded. Jean Norris was appointed to a low-level criminal court position focused on prostitution and family disputes, making her the state’s first woman judge. Heralded as an early step in women’s political empowerment, the selection seemed to be an unambiguous stride forward in women’s rights. But in order to fully appreciate the significance of this milestone, it’s revealing to juxtapose Norris’s appointment to another woman’s disappointment that same campaign season: Bertha Rembaugh lost an election that would have made her the first woman to serve as a judge in any of New York’s civil courts.

Though the fact that Norris and Rembaugh were even in contention for judicial posts was novel, their divergent experiences reflected and reinforced longstanding obstacles to women’s pursuit of public offices. Like generations before them, Norris and Rembaugh found that women had an easier time obtaining select positions. Initially deemed ineligible for all public posts, by the late-nineteenth century, women had gradually secured legal authorization to hold appointed positions—especially those focused on women, children, education, or charity. After women’s enfranchisement in 1917 removed the final legal obstacles to women’s officeholding (based on a contested understanding that suffrage included officeholding), social and political factors kept similar constraints in place. The path to the judiciary was especially “chilly,” as a journalist remarked at the time, yet it warmed more quickly for women seeking appointment to gendered judicial posts than for those running for election to a bench for which women could claim no special authority.

Women’s Eligibility for New York’s Public Offices

Long before Norris or Rembaugh could even contend for judicial posts, women in New York had to fight for the legal right to hold any offices at all. From the colonial period until Reconstruction, state constitutions governed qualifications to vote and hold state offices. As in many states, New York’s constitution limited suffrage to “male citizens” who met certain residency requirements. Also like many states, New York’s constitution did not specify if there were restrictions based on sex for public officers, including judges. This omission left the question of women’s eligibility open to argument.

New York politicians first squarely considered women’s eligibility for public offices in 1871, after newspapers across the nation publicized that women in Western territories and Midwestern states had secured positions as notaries public and even as justices of the peace. Many women sought to be notaries in this period because the position facilitated their work as law clerks and stenographers. The New York governor accordingly asked the state’s attorney general to advise him on whether he could appoint women to this position. The attorney general said no. In fact, he responded, women were ineligible for “election or appointment to any civil office within this State.” Under the state’s constitution, only men could vote and, he reasoned, “[it] seems to be the theory of our Constitution and laws, that all officers to be elected or appointed should be selected from the body of electors.”[1]

The fact that New York’s constitution did not directly address women’s eligibility allowed a reversal in women’s favor in the mid-1880s. When a new attorney general advised that women were eligible to compete with men under the civil service rules, he cast doubt on the earlier notary opinion but was not in a position to overrule it. Likely relying on this response, the governor appointed Jennie Turner, a lawyer and stenographer, as a notary. In January 1885, the defendants in a lawsuit challenged Turner’s authority in an effort to disqualify a document she had notarized. The judge in the case recognized that he faced a novel and debatable legal issue but concluded it would be up to the attorney general to challenge Turner’s authority, which did not occur. Seemingly reassured, the governor appointed five more women as notaries the following year.

During the surrounding decades, women made gradual progress in securing other offices in New York through statutory changes and new interpretations of existing laws. Their efforts showed both ongoing doubt about women’s legal eligibility as well as the gendered nature of the obtainable offices. In 1876, charity reformer Josephine Shaw Lowell was heralded as the first woman appointed to state office in New York, after she became the State Commissioner of Charities. In 1880, the legislature permitted women to hold some public school offices, joining more than twenty other states that had already made this move. In 1914, a suffragist’s appointment as the head of the Bureau of Child Hygiene of the Department of Health provoked eligibility skepticism, but she was permitted to hold the post. The same pattern—women mostly holding offices related to charity, education, and children—appeared in many other jurisdictions, even those with more generous attitudes toward women officeholders.

Campaigning for Women Judges

In the 1910s, New York women persistently demanded the right to be judges. Proponents, mostly women lawyers, strategically prioritized appointed positions in courts where they could claim special authority: the Children’s Court (which handled juvenile delinquency), the Night Court (which focused on prostitution cases), and the Court of Domestic Relations (which at the time had jurisdiction over criminal nonsupport cases). By sticking to these courts, discussants could claim women’s unique sensibilities and experiences would add valuable missing perspectives.

Legal authorization was needed before women could join the bench in these courts. In 1914 and 1915, women lobbied the legislature for the mildest possible advancement: permission for women to serve as “assistant” judges in the Children’s Court. They met stiff opposition. Male judges objected, explaining they could already rely on women probation officers when a woman’s involvement was needed. The all-male New York Bar Association charged that the proposed bill was unconstitutional, an argument reported in a column republished by newspapers across the country. The column’s anonymous writer explained in an exasperated tone: “‘Because there was no woman judge prior to April 19, 1775, therefore we can have no woman judge now!’ Something to do with some ancient common law or state constitution.” Though the writer found the premise ridiculous, the Bar Association was in good company. A leading 1871 Massachusetts case held the same. The New York legislature did not pass the bill.

After the Vote: Women in the New York Judiciary

After women won the vote in New York in 1917, one immediate question was what this meant for women’s officeholding eligibility. The state constitutional amendment merely deleted “male” from the qualifications for the franchise, arguably leaving officeholding rules unchanged. But this time the attorney general sided with women, reasoning that enfranchisement implicitly made officeholding rules gender neutral because of a perceived close connection between voting and holding office.

Before even receiving this legal opinion, just days after women won the vote, New York City women lawyers were already pursuing mayor-appointed judgeships. Sarah Stephenson sought a post on the New York City Children’s Court bench, noting that women had been “fighting for a long time for legislation” compelling the appointment of women to this court. Amy Wren pursued an appointment to the Brooklyn Magistrates’ Court, specifying she wished to serve in a proposed “woman’s court” division, which would hear low-level criminal cases against women. Both candidates were endorsed by the National Association of Women Lawyers (NAWL), an organization headquartered in New York City of which Stephenson was then president. “Now that women have a voice in the political world,” a Brooklyn newspaper suggested, “it may be that a larger measure of justice will be accorded them.” But neither woman was selected. Women continued pursuing judgeships in the next election cycle.

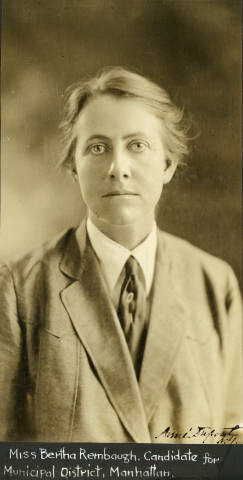

In October 1919, Bertha Rembaugh campaigned for the New York City Municipal Court. Rembaugh’s ambition was particularly bold, as the Municipal Court’s jurisdiction far exceeded subjects typically understood as women’s special domain. The court’s twenty-six judges heard a range of civil matters, such as employment, landlord-tenant, and personal injury claims. Rembaugh was a credible candidate: she was well-known and respected in New York City’s legal, charitable, and suffrage communities; she regularly volunteered at the Night Court; and she had published a book on the political status of women that examined women’s officeholding rights in every state.

To the extent sex factored into Rembaugh’s election strategy, she cast her identity as a matter of representation rather than substantive difference. According to a journalist who described her campaign, Rembaugh’s “clothes were of the sensible, mannish variety and her ideas … were of the same brand.” Rembaugh pointed out that about a third of the Municipal Court’s cases had a woman plaintiff or defendant, and nearly every case had a woman involved in some way. “I do not believe there is much difference between the viewpoint of the man and the woman as most people think,” she offered, “but, just the same, the people most concerned should be represented by one of their sex.” As a Republican in a Tammany Democrat district, Rembaugh faced a difficult path to victory. Still, according to the journalist, Rembaugh had a chance because she enjoyed bipartisan support from women—“It is a woman’s rather than a party campaign.” The real challenge was for a woman to be elected as a judge. The journalist continued, “If ever there was a chilly path for a woman’s feet to tread it is the road that leads to the bench.” The poll results revealed that “sex loyalty” hadn’t won the day, as Rembaugh was “snowed under.”

The honor of being the first woman judge in the state instead went to Jean Norris, a Tammany supporter whom the mayor appointed to fill a temporary vacancy on the Magistrates’ Court on October 27, 1919. The Magistrates’ Court was a low-level criminal court, with subdivisions including the Night Court and Court of Domestic Relations. And it was to these gendered subparts that Norris was assigned. Norris had long shown interest in these specialized courts. Unlike Rembaugh, Norris embraced what she perceived to be the special contributions women could make to the judiciary and suggested all courts needed a woman’s point of view. Rembaugh charitably cast Norris’s victory as her “consolation prize.” NAWL requested Norris be reappointed, which she was twice. (In 1931, she was among a group of judges accused of improper conduct. According to legal scholar Mae Quinn, Norris’s treatment during the investigation and her removal from the bench may have been unfairly influenced by sex.)

While Norris’s and Rembaugh’s differing results surely were due at least in part to party politics, they also followed and furthered the pattern of women’s easier route to posts viewed as gender appropriate. This trend continued in the following decades. The women who next secured judgeships—Clarice Baright (1925), Jeannette Goodman Brill (1929), and Anna Moscowitz Kross (1933)—all were nominated to serve in the gendered subparts of the Magistrates’ Court. No woman was elected to the Municipal Court until Agnes Craig’s victory in 1935. The New York Times covered Craig’s election under the headline: “New Woman Judge Boasts of Cooking.”[2] And still, gendered posts remained the more common opportunity. In 1935, NYC mayor Fiorello La Guardia—whose unprecedented support of women in government posts is explored in Elisabeth Israels Perry’s After the Vote: Feminist Politics in La Guardia’s New York—appointed Rosalie Loew Whitney and Justine Wise Polier to the recently redesigned Family Court, even though neither had notable experience or interest in family law. A few years later, he added Jane Bolin to the same bench, making her the country’s first Black woman judge.

In what scholars have termed the “Long Progressive Era,” gendered judicial benches opened opportunities for New York’s leading women lawyers yet simultaneously reinforced the understanding that only certain posts were proper for women. Echoing the days when women were legally ineligible for judicial posts (as well as many other categories of public offices), women were most successful in joining the judiciary when they sought appointment to gendered benches and stayed away from elected judgeships and those with broader jurisdiction.

Cover Image

“A Few of the Women Who Are Running for Nomination,” New York Tribune, Sept. 1, 1918, 34.

Elizabeth D. Katz, Ph.D., J.D.

Elizabeth D. Katz is an Associate Professor of Law at Washington University in St. Louis. She received a Ph.D. in History from Harvard University and a J.D. from the University of Virginia. Her newest article, “Sex, Suffrage, and State Constitutional Law: Women’s Legal Right to Hold Public Office,” is forthcoming in the Yale Journal of Law & Feminism. Follow her on twitter at @elizabethdkatz.