by Dr. Wesley Bishop

June 26, 2019

This is the second of two posts written by participants in the SHGAPE-sponsored lightning round at OAH 2019, “The Gilded Age and Progressive Era: Emerging Scholarship in the Field,” organized by Cynthia Heider. Read the previous post here.

Jeffrey Ostler once stated that the contentious field of Populist studies was, “one of the bloodiest episodes in American historiography.” The historiographical debate over Populism is, to say the least, long and nuanced. Historians as different as Richard Hofstadter, Walter Nugent, Lawrence Goodwyn, Elizabeth Sanders, Michael Kazin, John Judis, Jan-Werner Muller, Charles Postel, and Omar H. Ali (to name just a few) have all found different ways to interpret Populist movement of the nineteenth century and populism more generally. Yet what is particularly fascinating about the subject of Populism is that despite this considerable amount of scholarship, historians disagree over the most basic definitions and characterizations of Populism. Is Populism inherently right-wing, maybe even quasi-fascist, a form of mob rule tending toward authoritarianism? Is Populism a movement that is left-wing, emancipatory, one that promises more expansive democratic government? Is Populism none of these and merely a way of “doing politics”? These questions continue to animate the debate over Populism as we continue to study the late nineteenth century, begin periodizing the late twentieth, and navigate the early twenty-first.

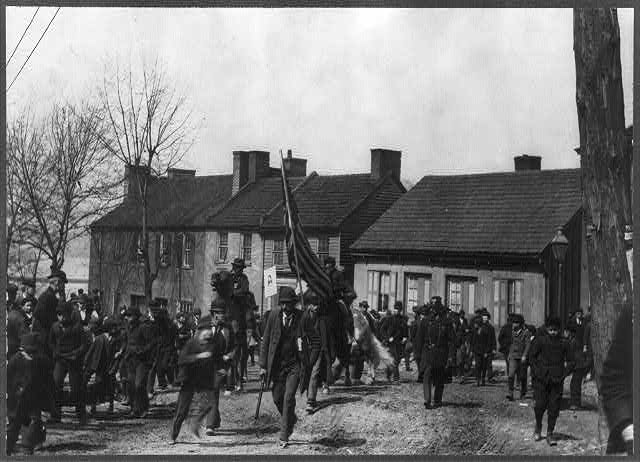

My research examines this question of Populism’s influence on American politics beginning with the first national march on Washington in 1894, typically referred to as “Coxey’s Army,” and tracing the impact of that march and its organizers on American politics up through the establishment of the New Deal Era.

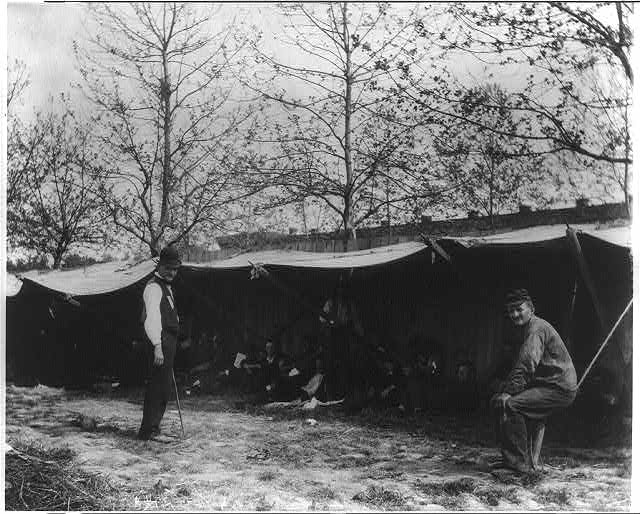

Previous scholarship has examined this march, noting the various idiosyncrasies and features that make Populism so fascinating. The march was organized by Jacob Coxey, a wealthy Ohio businessman, but was comprised mostly of unemployed workers; it was racially integrated, with black and white workers marching together during a time in which segregation and white supremacy in U.S. society was on the rise; and it was part of a broader Populist uprising in American society and politics following the Panic of 1893. As such, historians have identified the march as one of the major episodes in American Populist history. However, despite the national significance of the march, much of the works looking specifically at Coxey focus heavily on his activities in the summer of 1894. Although it is well known that he remained active in politics after 1894, there has been few extensive studies concerning his other campaigns, his brief term as mayor of Massillon, Ohio, and the political alliances he made well into the 1930s.

By extending the period of study to include Jacob Coxey’s long lifetime of activism, I argue that Coxey’s Army was both an expression of anger and concern over general inequality in American society and also a protest for specific demands that led to a broader shift in American politics. Marchers demanded a program for public works and a fiat currency for the United States. By focusing on the life and activism of Jacob Coxey, we see that both of these demands grew out of broader issues in American society and politics, and reflects a longer history linking the activism of greenback labor to the New Deal.

One of the most interesting and understudied aspects of the march was how Coxey linked the currency debate to his overriding concern for unemployment. Coxey took part in the era’s wide-ranging debate over whether or not the U.S. should rely upon a gold, silver, or fiat standard for its currency. Coxey, who had roots in the greenback labor movement in the 1870s, continued to adhere to the fiat currency position, even as other populists and labor activists had turned to silver as a solution. Coxey hoped that the Populist uprisings of the 1890s would provide an opportunity to wed this greenback-labor outlook to the broader movement of labor-populists to establish a more socialist commonwealth in the United States. Long after 1894, Coxey continued to organize marches on themes such as these. In doing so, he contributed to the long tradition of American social movements’ efforts to reshape and redefine the popular concept of “the people.”

My research, then, focuses on four major ideas/arguments. First, I am among those who view American Populism as a broad-based, elastic movement with no specific or essential ideological character. Attempts to define Populism as either reactionary or radical miss the broader point that Populism could (and often has) take on various political flavors, depending on how such movements have positioned themselves in opposition to the American state, economy, and civil society.

Second, Coxey’s Army was not important merely as a communicative act. Instead, Coxey’s Army was significant because it helped reconceptualize “the people” and force politicians to reconsider programs of economic and social welfare. We can see this most clearly at the presidential political conventions of 1896, where the Democratic, Republican, and short-lived People’s Party all were forced to contend with the fallout of the summer of 1894 and

the concerns of working-class people.

Third, the concept of the commonweal was part of a much deeper and intellectually rich fight between activists and thinkers in the Gilded Age, Progressive Era, and New Deal. The “commonweal,” a shortened version of the concept of “commonwealth,” differed greatly depending on which movement, actor, and period discussed it. But essentially it was a concept that dealt with a more just and equitable organization of American society. The socialist, and labor-populist journalist and activist Henry Demarest Lloyd discussed the concept in detail following the 1894 march, arguing that it represented a new phase of American society. “The Co-operative Commonwealth is the legitimate offspring and lawful successor of the republic,” Lloyd explained during a speech at a convention in October of 1894. “Our liberties and our wealth are from the people and by the people and both must be for the people. Wealth like government is the product of the co-operation of all, and like government must be the property of all its creators, not of a privileged few alone.”

Yet, this concept was far from agreed upon, especially when activists in the labor, populist, and socialist movements envisioned how this commonweal would be established. At stake was how movements and parties conceptualized the social, economic, and political order of the United States, what was the common good, and most importantly how should the country be governed? In this regard, the currency question, far from being a panacea and distraction (as some labor-populists such as Henry Demarest Lloyd asserted), was central to how activists envisioned the role of the market and state in a more equitable society.

Finally, I look at the understudied career of Coxey after the march, specifically his time in the Democratic, Republican, People’s, Socialist, Farmer-Labor, and Union Party, and his brief tenure as mayor of Massillon, Ohio in the opening of the New Deal era. His failures, especially as mayor, raises further questions about the promise and limitations of American Populism, both as a protest style and political force.

Dr. Wesley Bishop

Wesley Bishop is an assistant professor of American history at Marian University in Indianapolis. He studies the history of American political thought, the working class, and social movements.