By Donald Thomas Hickey

July 18, 2018

Historians measure change over time in many different ways. When examining the cultural history of the American Civil War Era, for example, analysis of popular literature from Harriet Beecher Stowe’s incendiary Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852) to Jefferson Davis’ turgid The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government (1881) reveals the conflicting ways Americans recorded their experiences of the secession crisis, war, and the uncertain peace that followed. Moreover, popular literature can also create history, as with Thomas F. Dixon’s novel, The Clansman: A Historical Romance of the Ku Klux Klan (1905), which played a central role in shaping post-Civil War culture of the United States. The Clansman was a thinly veiled polemic against biracial Republican “misrule” of the immediate postwar South. In Dixon’s egregiously racist rendering, the folly of rapacious Reconstruction Republicans and their political enabling of Southern Blacks nearly destroyed the South before the heroic Ku Klux Klan reasserted white supremacy. Ten years later, D.W. Griffith adapted The Clansman into the epic film, The Birth of the Nation, which held the honor of an early screening in Woodrow Wilson’s White House.

When Civil War veteran Ambrose Bierce’s signature volume, Tales of Soldiers and Civilians, appeared in 1891, most Gilded Age fiction openly promoted reconciliation. Published as a rejoinder to the sentimental Civil War fiction and non-fiction of the 1880s and the proliferation of what Bierce detected as self-aggrandizing soldier-reminiscences, Tales of Soldiers and Civilians instead demonstrates some of the most apolitical and lurid, if cryptic, Gilded Age literary treatment of American Civil War.[1]

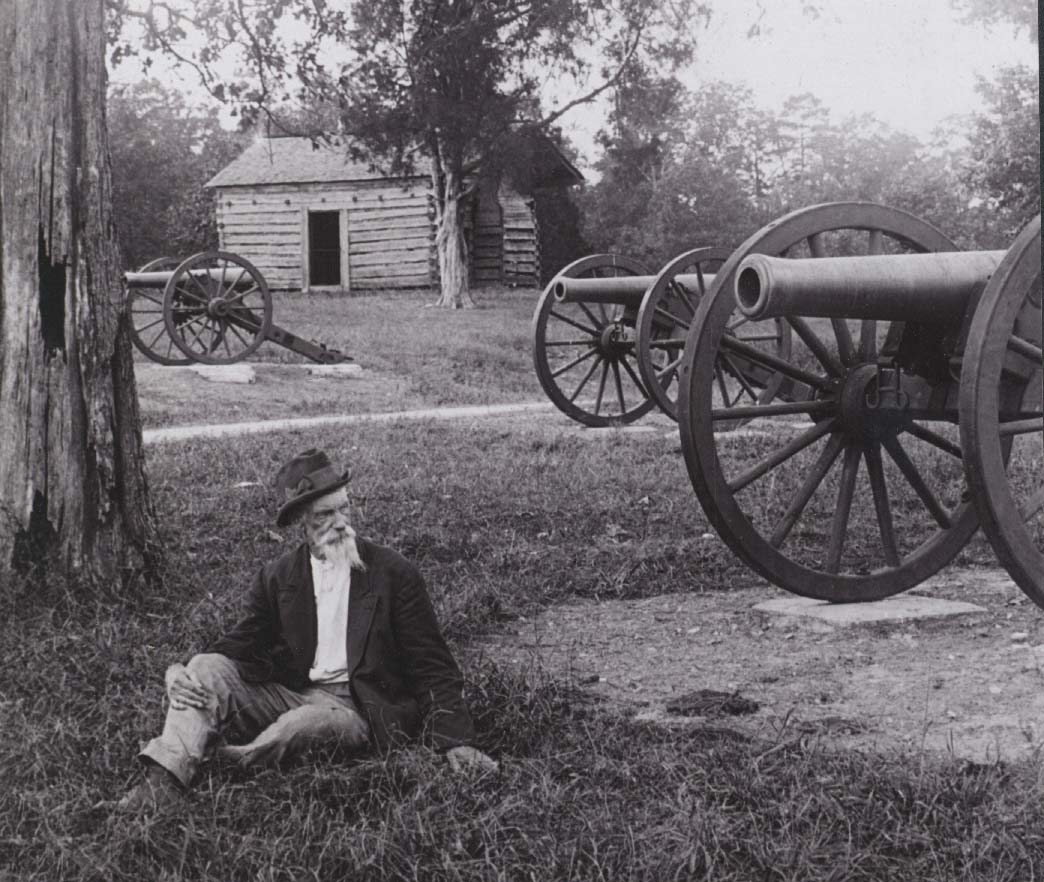

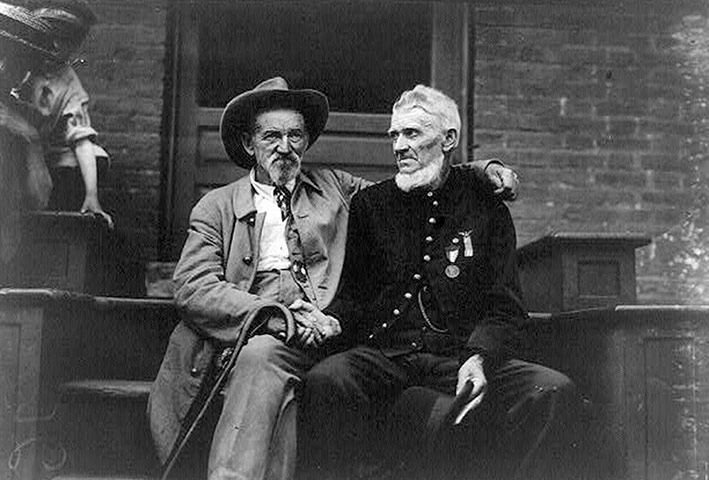

Bierce was born in Meigs County, Ohio in 1842. In 1861, he enlisted in the Union Army’s 9th Indiana Infantry Regiment in response to the outbreak of the Civil War. Commended for bravery in multiple battles, he was eventually promoted to brevet major. After the war, Bierce settled in San Francisco, securing employment as a journalist, editor, and short fiction author. In 1913, after travelling back to the South to visit a Civil War battlefield of his past, Bierce was drawn in by yet another civil war, this time the convulsions of the Mexican Revolution. Rumors suggest he caught up with Pancho Villa’s rebel army, but Bierce soon after disappeared and was never seen nor heard from again.

Drawing on his experience as a combat veteran, Bierce’s stories graphically depict Civil War death in ways that foreshadow a modernist disillusion and cynicism more commonly associated with World War I era literature. Tales of Soldiers and Civilians signaled a challenge, a quarter-century after Appomattox, to what constituted the appropriate rendition of the war’s suffering and death. Death’s significance for the nineteenth-century generation centered on prevailing Victorian assumptions about life’s “proper end”—about who should die, when and where, and under what circumstances. While the majority of Gilded Age American writers sought to valorize and sentimentalize these deaths in the service of national reunion, Bierce’s portrayal of war death mocked these reconciliationist pretensions. In one especially graphic tale, “Chickamauga,” Bierce subverted what audiences of the 1890s expected from a Civil War yarn—heroism, bravery, and sacrifice. Instead, “Chickamauga” spoke of the suffering of civilians. In one scene, a young boy discovers a wounded soldier described as having a “face that lacked a lower jaw—from the upper teeth to the throat was a great red gap fringed with hanging shreds of flesh and splinters of bone.”[2] This same unfortunate boy shortly thereafter discovers that his home has been destroyed by shelling, and finds his mother in this state: “the greater part of the forehead was torn away, and from the jagged hole the brain protruded, overflowing the temple, a frothy mass of gray, crowned with clusters of crimson bubbles—the work of a shell.”[3]

These kinds of characterizations contrasted jarringly to popular Civil War literature at the time, but without offering any reasons for doing so. Bierce’s Tales of Soldiers and Civilians did not serve to enlighten the reader of the lessons of the Civil War as much as they did to underscore its costs. His depiction of the war resisted subsumption into the Gilded Age’s rush to sanitize, valorize, and celebrate the dead of the American Civil War. Bierce, in this reading, is more a proto-existentialist than antiwar, and is thus all the more valuable a resource in expanding the scope of our historical understanding of American reunion. Such a rethinking, I argue, is needed to understand both the limitations of Blight’s Gilded Age reconciliation consensus but also the roots of wartime existentialism most often attached to World War I.

Donald Thomas Hickey

Donald Thomas Hickey is a PhD student at the University of California, Santa Cruz, focusing on nineteenth century cultural and intellectual U.S. history, especially the post-Civil War Far West, and can be reached on Twitter @dthomashickey.