By Thomas Jepsen

June 13, 2023

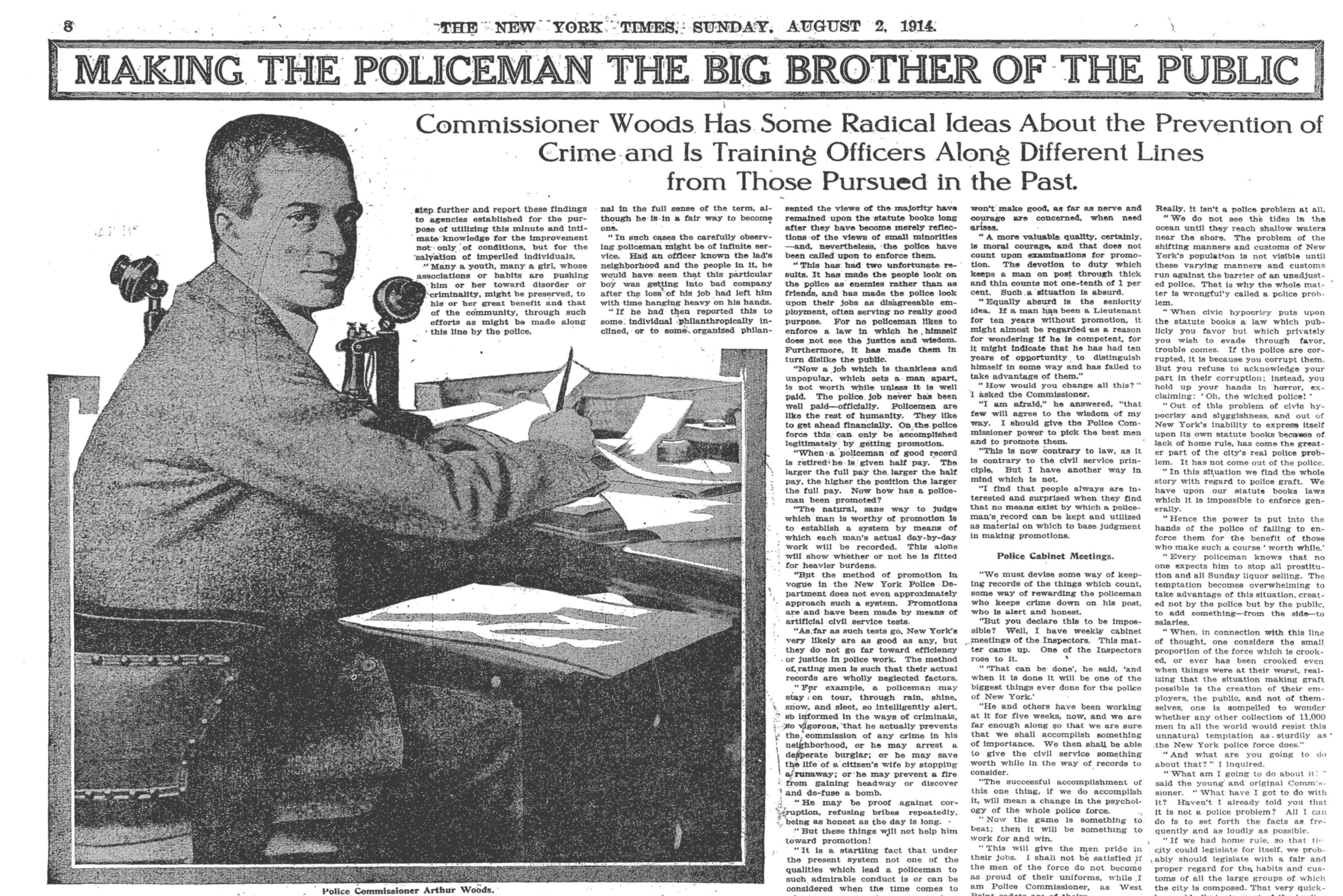

This is part of a series of blog posts on crime and punishment in the Gilded Age and Progressive Era, covering histories of violence, law, criminal justice, and incarceration. Read the posts in this series here and find the CFP here. For a multimedia take on the wiretapping scandal of 1916, see Jepsen’s video essay, “Making the Policeman the ‘Big Brother’ of the Public.”

In the years before the United States entered the First World War, New York City was beset with a wave of crime and civil unrest. Violent crimes and prostitution were rampant and often unpunished, and anarchists called for the violent overthrow of the government. A corrupt municipal government, dominated by Tammany Hall, attempted to counter this with a brutal police crackdown, resulting in accusations of unnecessary brutality. The mayoral election of 1913 swept a young reformer, John Purroy Mitchel, into office as the candidate of the Fusion Party. His police commissioner, Arthur H. Woods, pledged to solve the crime problem and quell public disturbances by instituting a series of police reforms based on the progressive principles of “scientific management.” However, one of these initiatives—use of a police wiretapping unit for the clandestine gathering of information—led to a public scandal and contributed to the downfall of the reform movement in New York City.[1]

Arthur Woods was the son of a wealthy Boston textile executive; after graduating from Harvard and the University of Berlin, he taught English at Groton before becoming a journalist in New York City. While working as a reporter for the New York Evening Sun, Woods made the acquaintance of New York City Police Commissioner Theodore A. Bingham, who appointed him deputy police commissioner in 1907.[2]

Woods’ experience as a journalist enabled him to promote his concept of policing in print. Writing in the May 1909 issue of McClure’s Magazine, Woods placed the blame for the high crime rate in New York City on recent immigrants from southern Europe. He pointed to the problem posed by lax immigration policies, which he alleged enabled criminals from Italy to enter the United States illegally and form organized gangs. His proposed solution was to adopt “special surveillance,” an expanded form of probation used by the Italian police to monitor the activities of suspected criminals in their daily lives. To implement special surveillance in the United States, Woods further proposed creation of a “secret police system,” arguing that “to handle this sort of exotic crime the most searching secret service work is necessary.” Betraying a prejudice against southern Europeans not uncommon in his social class at the time, Woods added that if his proposals were put into practice, “the jails would be more full of swarthy, low-browed convicts.”[3]

After a brutal police attack on demonstrators at a Union Square rally, Mayor Mitchel used the opportunity to fire Police Commissioner Douglas McKay and promote Woods to that position on April 8, 1914.[4] Woods sought to restore public order by ordering police to refrain from violent actions, explaining that some of the protesters “would try to make themselves martyrs and desired nothing more ardently than to have the police assault them.”[5]

He began a program of reform of the New York City Police Department that reflected principles of the Good Government movement by limiting the influence of machine politics. He replaced a promotion system based on cronyism with a merit-based plan for advancement. He introduced concepts of sociology and criminology in police work and addressed the need for a better educated police force by establishing a police academy. Woods pioneered the use of recently developed technologies in police work. Woods purchased motion picture filming equipment in order to create “moving pictures of criminals in their daily walks of life,” to be used in training young detectives and was an early implementer of police radio to enable rapid communications between police stations in emergencies.[6]

As he had suggested in his 1909 McClure’s article, one of Woods’ primary goals was improving surveillance of suspected criminal activity in order to change the focus of policing from crime detection to crime prevention. Woods promised to focus on prevention by turning the cop on the beat into a trained observer of his community. As he maintained in a 1914 interview, “The old conception of police work especially charged the force with the detection of criminals… after crimes had been committed. The new conception… demands the establishment of a force, first, large enough, and second, sufficiently well trained to prevent the commission of crime through sheer organized watchfulness.” Using a phrase that had yet to acquire its Orwellian connotation, the New York Times titled the interview “Making the Policeman the Big Brother of the Public.”[7]

Woods’ penchant for surveillance and “organized watchfulness” was not limited to monitoring suspected criminal activity. Informants within the Police Department sent him confidential reports on morale in different precincts, interactions with the public, and what the average cop on the beat thought about the commissioner.[8]

Telephone wiretapping represented a form of surveillance technology already available to Woods and the police department. The New York Police Department had begun secretly tapping the telephone conversations of persons suspected of criminal activity in 1895. At the time, no laws existed regarding the legality of obtaining evidence by wiretapping and so, with the full cooperation of the New York Telephone Company, the police were able to listen in on any telephone call in New York City.[9]

The Wiretapping Scandal of 1916

In the spring of 1916, Mayor John Purroy Mitchel vowed to investigate and improve conditions in publicly supported orphanages, including those run by the Catholic Diocese. An investigation headed by Commissioner of Public Charities John A. Kingsbury found that conditions in some of the orphanages were substandard, and in some cases, truly Dickensian. In one institution, 200 children were found sharing a single toothbrush and bar of soap.[10]

A Catholic priest, Father William Farrell, felt that the Catholic Diocese was being unfairly singled out for scrutiny, and wrote a series of anonymous pamphlets criticizing Mitchel’s administration and the investigation. Convinced that Farrell was the ringleader of a conspiracy to defame the city government, Kingsbury asked Woods to have the Police Department tap the wires of Farrell and other officials of the Catholic Diocese.[11]

Suspecting that his telephone had been tapped, Farrell engaged in a number of staged telephone conversations with his superior, Monsignor John Joseph Dunn, in which they made up stories and fabricated non-existent plots. His suspicions were confirmed when investigators began to refer to details of the nonexistent plots in their questions. Farrell went public with the wiretapping allegations and demanded an apology from Mitchel. Headlines appeared in New York City newspapers, accusing the mayor and police commissioner of tapping the telephones of Catholic priests. It was, their Bishop opined angrily in the pages of the New York Tribune, “about the most outrageous offence on the constitutional rights of the people that has ever been committed here.”[12] Brooklyn District Attorney Harry E. Lewis announced that a Kings County Grand Jury would consider the charges of wiretapping by the police.[13]

Woods defended the use of wiretaps by the police, stating that it was “one of the most valuable methods we had.” He was supported by Mitchel, who praised the work of his police commissioner in reducing crime in New York City.[14] Although a practicing Catholic, Mitchel began to receive anonymous letters accusing him of anti-Catholic bias for ordering the charity’s investigation and allowing the wiretapping.[15]

While the Kings County Grand Jury failed by one vote to bring an indictment against the mayor, his image as a reformer had been tarnished by the scandal. The Grand Jury found that “the conduct of the Mayor and the Police Commissioner merits most severe condemnation” for approving the wiretap.[16]

What is “Progressive Policing”?

Arthur Woods termed this new style of policing “progressive policing,” but what did he mean by that term? Woods’ use of surveillance instead of force can be seen as an example of “scientific management” as progressive reform. Scientific management, as defined by Frederick Winslow Taylor in his 1911 monograph, The Principles of Scientific Management, and applied to industrial management, involved close observation of work with the goal of increasing efficiency and productivity.[17] Woods’ derived strategy of “organized watchfulness” made police power less visible, while relying on undercover agents and wiretapping to keep track of those suspected of crime and political dissent. But the perceived violation of the public’s right to privacy led to the downfall of the progressive administration it was intended to support.

Allegations of warrantless wiretapping by the police in 1916 is particularly significant because it took place at a time when the legality of such actions had not yet been firmly established by the courts. While cases involving interception of telegrams had been tested by state courts in the nineteenth century, and the assertion of a “right to privacy” had been proclaimed by Louis Brandeis and Samuel Warren in an essay in the Harvard Law Review in 1890, the law had not yet caught up with the widespread use of the telephone for communications.[18] Woods escaped criminal prosecution in the wiretapping case due to an interpretation of an 1895 New York State law which permitted the police to use wiretapping to investigate criminal activity.[19] However, use of this legal loophole in his defense required Woods to allege criminal activity on the part of the priests, a claim which enraged many Catholics.

The wiretapping case revealed a class divide between the predominantly White Anglo-Saxon Protestant Progressives of the era and working-class Catholics, many of whom were recent immigrants. Woods’ Harvard education and prejudice against immigrants made him a target of charges of elitism. As Kirsten Swinth points out in her essay on Progressive reform, “The good government movement attracted men of good standing in society,” but many of these same men were “suspicious of the lower classes and immigrants.”[20]

Woods’ use of surveillance techniques in his attempt to reform the New York Police Department points to a fundamental contradiction in the progressivism of the era and an unanswered question. Does the emergence of a surveillance state represent the logical outcome of the progressive belief in “bureaucratic management” or is it an aberration? Does the “search for order” lead ultimately to repression? This is a contradiction perhaps best understood by considering Robert Wiebe’s view of progressivism as an unfinished product—a “loose framework” with a “plastic center” that “invited precisely that sort of contradictory experimentation.”[21]

For a multimedia take on the wiretapping scandal of 1916, see my video essay, “Making the Policeman the ‘Big Brother’ of the Public”:

Thomas Jepsen

Thomas Jepsen is a historian of technology. His publications include My Sisters Telegraphic: Women in the Telegraph Office, 1846-1950 (Athens: Ohio University Press, 2000) and “’A New Business in the World’: The Telegraph, Privacy, and the U.S. Constitution in the Nineteenth Century,” Technology and Culture 59, No. 1 (Jan. 2018).