By Dr. Jonathon Booth

April 19, 2023

This is the first in a series of blog posts on crime and punishment in the Gilded Age and Progressive Era, covering histories of violence, law, criminal justice, and incarceration. Read the posts in this series here and find the CFP here.

During the two centuries before 1865, the U.S. South was governed by and for slaveholding planters. Southern law gave these enslavers almost total authority over the lives of enslaved people. To boost the agricultural production that built their fortunes and made them some of the richest people in the country, planters frequently resorted to brutal and violent methods. The Civil War, however, destroyed the legal institution of slavery and, with it, the legal power of the slaveholder.

At the end of the war, Southern states faced the question of how to maintain the cotton economy without slavery, or in the words of the Georgia Senate’s Committee on Freedmen, “How are we to control this free labor?”[1] Their solution was to transfer the legal power over Black Southerners that had been held by slaveholders to the state. In Georgia, the creation of a new County Court system was at the heart of this plan. Georgia’s white politicians believed that a local court, which would be controlled by white elites and would have broad discretion to punish minor offenses, was the perfect solution. It would keep Black Georgians at work in the cotton fields and provide a way to criminalize Black leaders who attempted to organize to win economic and political power. During their brief time in power, the Republicans, who supported abolition and equal rights, eliminated the County Court and attempted to create a more equitable justice system, but after Reconstruction was overthrown, Democrats recreated it and made it a pillar of Jim Crow justice.

When they had been enslaved, Black Georgians were subject to the authority of their enslavers, but now that they were free, they had to be brought under the authority of the state government. To accomplish this goal, Georgia’s leaders quickly drafted a new state constitution that defined the legal status of the state’s Black population. In late 1865, the constitutional convention, controlled exclusively by white Democrats, created a committee “to provide by law for the government of free persons of color … guarding them and the State against any evil that may arise from their sudden emancipation.”[2] The committee acknowledged that its task was vital because “immediate legislation on this important matter is demanded and expected by the Planting interest of the country.”[3] The committee proposed a “Black Code,” one of many proposed or enacted across the South, that laid out the minimal freedoms and many restrictions of the newly freed population. It allowed freedpeople to marry, own property, make contracts, and give testimony in cases where other persons of color were involved. It also proposed that criminal punishments for Black Georgians be more severe than for white Georgians and that a class of crimes should be created that could be committed only by Black people. To enforce these new laws and discriminatory punishments, the committee recognized that an expanded court system would be necessary.

During slavery, Georgia’s criminal justice system had applied almost exclusively to free people. Although enslaved people occasionally appeared in court, they were much more likely to be punished in private on the plantation, most often whipped by an overseer. Emancipation meant that nearly four million formerly enslaved people across the South were suddenly subject to the public authority of the courts. Before the Civil War, each Georgia county had its own trial court, known as the Superior Court, which heard a full range of both civil and criminal cases and whose decisions could be appealed up to the state’s Supreme Court. The Superior Court, however, met just twice a year in most counties. Due to its infrequent meetings and relative commitment to procedural fairness, Georgia’s white elites considered it insufficient to maintain the subordination of the newly freed Black population. Consequently, the committee proposed the creation of a County Court system to supplement the existing Superior Courts.

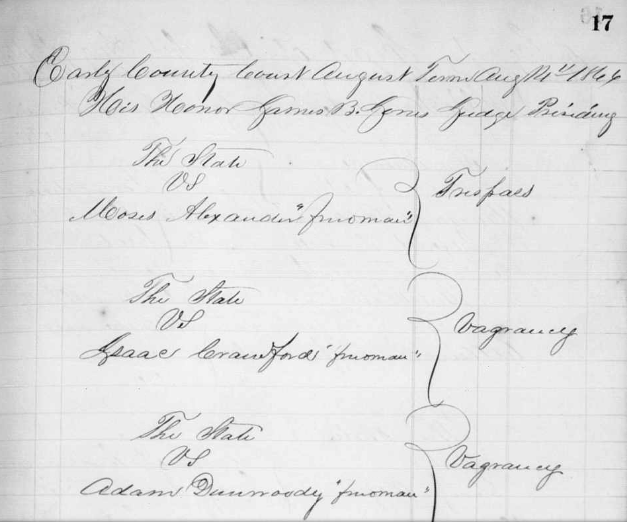

As proposed, the County Court would meet at least four times per year and would hear both criminal offenses by Black Georgians and civil lawsuits about wages and working conditions. The committee believed that the County Court could handle the conflicts that were expected to occur as freedpeople began to work for wages and could make sure that freedpeople who stepped out of line were swiftly punished. (Serious felonies, such as murder and arson, would still be tried by the Superior Courts after 1865, but the County Courts were now responsible for all minor offenses, which made up the majority of cases in the state.) The committee believed that, combined with the broad restrictions of the proposed Black Code, the County Court would help maintain cotton production and the state’s racial hierarchy, even with slavery abolished.

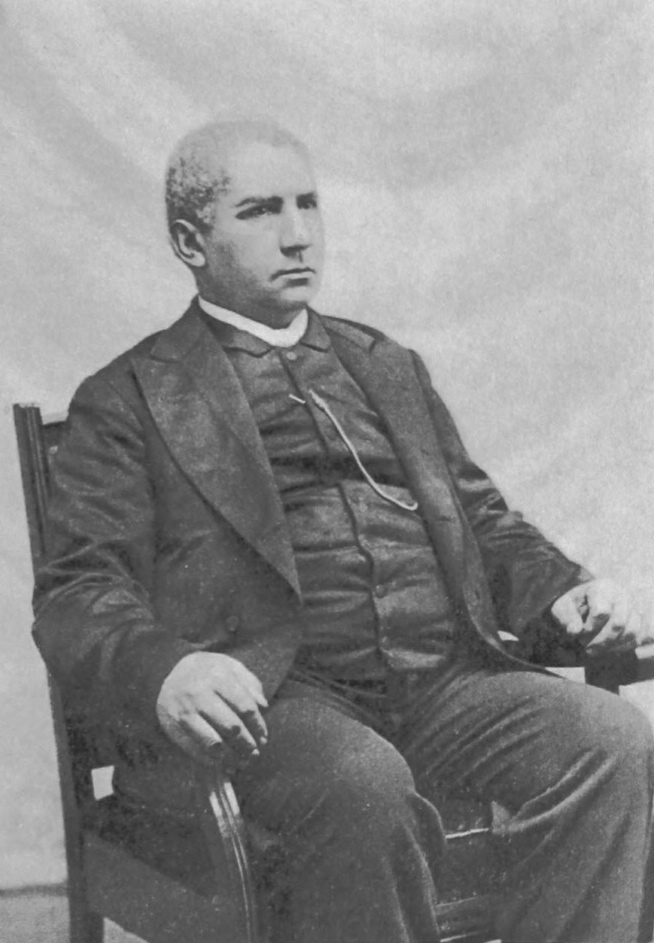

Black Georgians objected to the proposed Black Code and its attempt to encode racial subordination in law. A freedmen’s convention, attended by Black leaders including Rev. Henry McNeal Turner, denounced the proposal and demanded equal citizenship rights as well as laws that were “equitable and progressive.”[4] The convention argued that during slavery “we had as many different laws, as we had masters…. But now a uniform system of laws must govern us.” Their anger was shared by Northern Republicans who feared that slavery would be recreated through oppressive laws. In response to oppressive Southern laws, Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1866, which forbade states from passing overtly discriminatory legislation such as Georgia’s proposed Black Code. Georgia’s elites, however, realized that they could accomplish the same goals through legislation that did not explicitly discriminate on the basis of race.

The County Court, modified to be race neutral, exemplified this new strategy.[5] Georgia’s legislators recognized that they could comply with the Civil Rights Act by granting local sheriffs and judges discretion and trusting them to use their positions to enforce white supremacy. The County Court soon became, in fact if not in law, a court almost exclusively for Black Georgians. In addition, new laws made the County Court a key instrument to police Black labor. For example, those charged under the post-emancipation vagrancy act, which was intended to keep freedpeople working on cotton plantations, were tried exclusively in the County Court rather than the Superior Court. In addition, the legislature revised the state’s criminal code to expand the power of the County Court. The revision increased the punishments for some serious felonies while reducing the punishments for property crimes. Georgia’s legislators assumed that property crimes would be committed mostly by freedpeople, and the lesser punishments allowed them to be tried and punished in the County Court. Quickly, minor thefts, especially the theft of food, forced many Black Georgians into the County Court. They were quickly found guilty and sentenced to build roads on the county chain gang, where forced labor was permitted by the Thirteenth Amendment’s exception allowing involuntary servitude as punishment for crime.

White Georgians celebrated this accomplishment. One newspaper argued that the “speedy trial and punishment” of Black Georgians showed them that “labor on a plantation is preferable to the hard, and precarious life of a vagrant.”[6] Once the County Court was established, a correspondent from Newnan, Georgia, reported that it had the “desired effect” of forcing Black Georgians out of the town and back to the plantation areas.[7]

This first version of the County Court system, like Presidential Reconstruction, was short-lived. Georgia was put under military rule by the Reconstruction Act of 1867 and was required to give all adult men the right to vote. Black voting rights made significant political change possible. In 1868, these newly enfranchised voters ratified a new constitution and narrowly elected Republican Rufus Bullock governor, the last Republican elected to the role until 2003. Georgia’s 1868 constitution abolished the County Court system because its drafters understood that it was a tool for Black oppression. Still, there was an obvious need for even-handed justice for minor offenses, so the Republican legislature expanded the jurisdiction of justices of the peace to fill the gap created by the elimination of the County Court. This strategy worked badly, however, because justices of the peace were under-resourced and overwhelmed with cases, many brought by white landowners against their Black employees. Republicans then attempted to create a “District Court” system, which could both handle caseloads and treat Black Georgians fairly. This system, like all aspects of Reconstruction in Georgia, survived for only a few years.

When Democrats regained control of the state legislature in the violent election of 1870 – and the governor’s office in 1871 – they moved to recreate the County Court system. This push was part of a broader effort to reassert Democratic control at the county level, where Black Georgians had elected many local officials, including sheriffs. One key tactic of Georgia’s Democrats was to apply certain laws, such as those restricting hunting and fishing, only to Black-majority counties. Although they weakened Black Georgians’ economic prospects, these laws did not violate the Civil Rights Act of 1866 and Fourteenth Amendment because they did not discriminate against Black Georgians as individuals but rather applied to counties as a whole. White residents of the affected counties were confident that local officials would exercise discretion to make sure state laws were enforced only against Black Georgians. The legislature applied this strategy to the County Court, establishing it only in counties with significant Black populations. In addition, since Black Georgians continued to exercise the right to vote in the 1870s, the judges of the second iteration of the County Court system were appointed by the governor rather than elected. As with their first attempt at the County Court system, their second attempt was similarly designed to uphold the state’s racial hierarchy and control Black labor.

With Republicans finally banished from power in the 1870s, the County Court system became the most important institution of Jim Crow justice in rural Georgia. Staffed by white elites, the County Courts were available to punish Black workers who committed minor offenses or simply challenged the state’s racial hierarchy. This state violence was supplemented by the private violence of lynching. After the defeat of Reconstruction, then, Georgia’s politicians were able to create a system that guaranteed continued cotton production and white supremacy while complying with federal laws by trusting local law enforcement to exercise discretion. A legal system that was formally race-neutral still functioned as an engine of racial hierarchy.

Dr. Jonathon Booth

Jonathon Booth received his PhD from Harvard University in 2021 and his JD from Harvard Law School in 2019. He is currently working on a book manuscript tentatively titled "Dethroning Justice: Race, Law, and Police after Slavery" and an article titled "Dred Scott as Law, 1857–1868."