By Dr. Joseph M. Gabriel

July 21, 2020

This is the first of two posts on teaching the 1918 influenza pandemic, as part of a series exploring the lived experience of Americans during the pandemic. Read part two here. Read the other posts in the series here.

The influenza pandemic of 1918 is often left out of history courses and other classes that cover the early twentieth century. Unfortunately, COVID-19 has made the topic newly relevant and as a result many educators may want to add a lecture or other material on the 1918 pandemic into their courses. In this post I’d like to offer some general information about the 1918 pandemic and some suggestions about how to discuss it with students in the context of COVID-19 that might be helpful for historians and others who do not have a lot of experience with the history of medicine or public health. In a follow-up post I will then discuss some ideas, themes, and exercises that I think can be usefully incorporated into classroom discussions of the 1918 pandemic. My focus in both posts will be on the United States and on themes geared toward general history courses (as opposed to, say, clinical education for healthcare providers). Given the nature of the topic, some of my discussion may veer into territory that is unfamiliar to many historians who do not teach medical history or the history of science. In particular, I will discuss some of the differences between influenza and coronaviruses and why these differences are important to keep in mind when teaching the 1918 pandemic. I’ll also touch briefly on how the distribution patterns of the two pandemics differ. Please bear with me. In my view, teaching this topic properly at this moment in time requires some familiarity with these types of issues.

To begin with, you should make it clear to your students that influenza and COVID-19 (short for “Coronavirus disease 2019”) are different diseases and that this difference matters. You should also make it clear that both diseases are caused by viruses (as opposed to bacteria) and that viruses evolve and therefore change over time. This might seem obvious, but it really is not. Many students do not know that bacteria and viruses are different types of organisms and as a result do not understand why antibiotics can be used to treat one but not the other. And most students are not used to incorporating an evolutionary perspective into their understandings of historical change. In my view, however, doing so at least at a basic level is important if we want to properly contextualize the 1918 influenza pandemic. There are actually four types of influenza virus (A, B, C, and D), the first two of which cause the large majority of influenza cases in humans. Influenza A also circulates widely in a variety of animal populations, including swine and birds, and is responsible for the major pandemics that have caused large loss of human life, including the 1918 pandemic. Influenza A is further divided into multiple subtypes based on variations in two surface proteins (labeled H1-H18 and N1-N11) and designated by alphanumeric combinations such as H1N1 (a strain of which caused the 1918 pandemic) and H5N1 (the so-called “avian flu”). Each of these subtypes, in turn, is comprised of a variety of circulating strains with novel forms periodically emerging as a result of mutation. Exposure to a strain of influenza virus can confer partial or full protective immunity to that and similar strains, and a variety of influenza vaccines are available that, while not always effective, reduce the rate of infection overall. Thankfully, the strain of H1N1 that caused the 1918 pandemic no longer exists in the wild—although reconstructed forms of the virus have recently been created and studied in laboratory settings.

SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, belongs to an entirely different class of virus known as “coronaviruses” and should therefore be clearly distinguished from influenza viruses. Coronaviruses circulate in both human and animal populations. There are no vaccines. There are four types of common human coronavirus which circulate widely and typically cause mild to moderate upper respiratory illnesses (including the common cold). There are also three types of highly pathogenic coronavirus which have recently circulated in humans: MERS-CoV (which first appeared in humans in 2012), SARS-CoV-1 (which first appeared in humans in 2002 and has since been contained, with no new known cases since 2004), and SARS-CoV-2. Although MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV-1 are both highly dangerous viruses, so far their global impact has been relatively small. Not so SARS-CoV-2 which has, as I write this in mid-June, been responsible for more than 420,000 deaths worldwide since the first cases of COVID-19 were identified in December of 2019.

All this is important to keep in mind because faulty comparisons between “the flu” and COVID-19 that downplay the severity of the current pandemic are commonplace. SARS-CoV-2 is far more dangerous than any of the strains of influenza virus currently circulating. Although we still do not know the true rate of transmission, COVID-19 appears to be significantly more contagious than influenza, appears to have a significant dormant period in which transmission by pre-symptomatic carriers is possible, and can lead to a variety of severe long-term health problems in a way that influenza does not, including heart disease, neurocognitive impairment, and permanent lung damage. Thankfully, SARS-CoV-2 does not appear to be as lethal as the strain of H1N1 influenza that caused the 1918 pandemic, but it is clearly more dangerous than the other strains of influenza A and B now circulating (including other strains of H1N1). Comparing the 1918 influenza pandemic to the COVID-19 pandemic without making clear the distinction between the two diseases and the way that influenza viruses have changed over time may lead to significant confusion. As I discuss at the end of the post, it may also lead students to underestimate the threat posed by novel coronaviruses and strains of influenza A. And, perhaps most importantly, simplistic comparisons between the two can obscure the fact that at this point we simply don’t know very much about COVID-19, including whether or not people develop significant immunity after exposure to the virus and whether or not the development of a vaccine is even feasible. We don’t yet know how our own story ends.

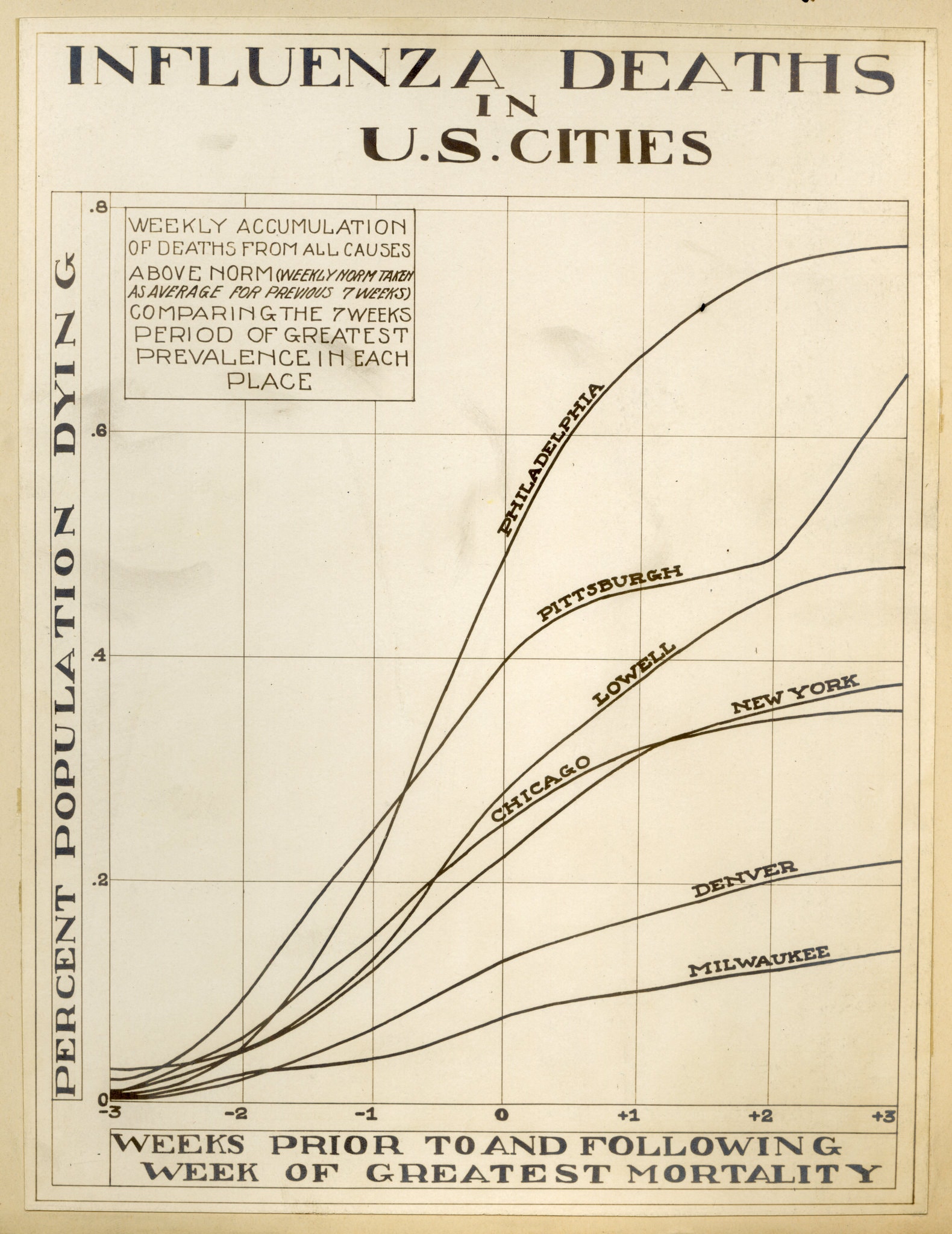

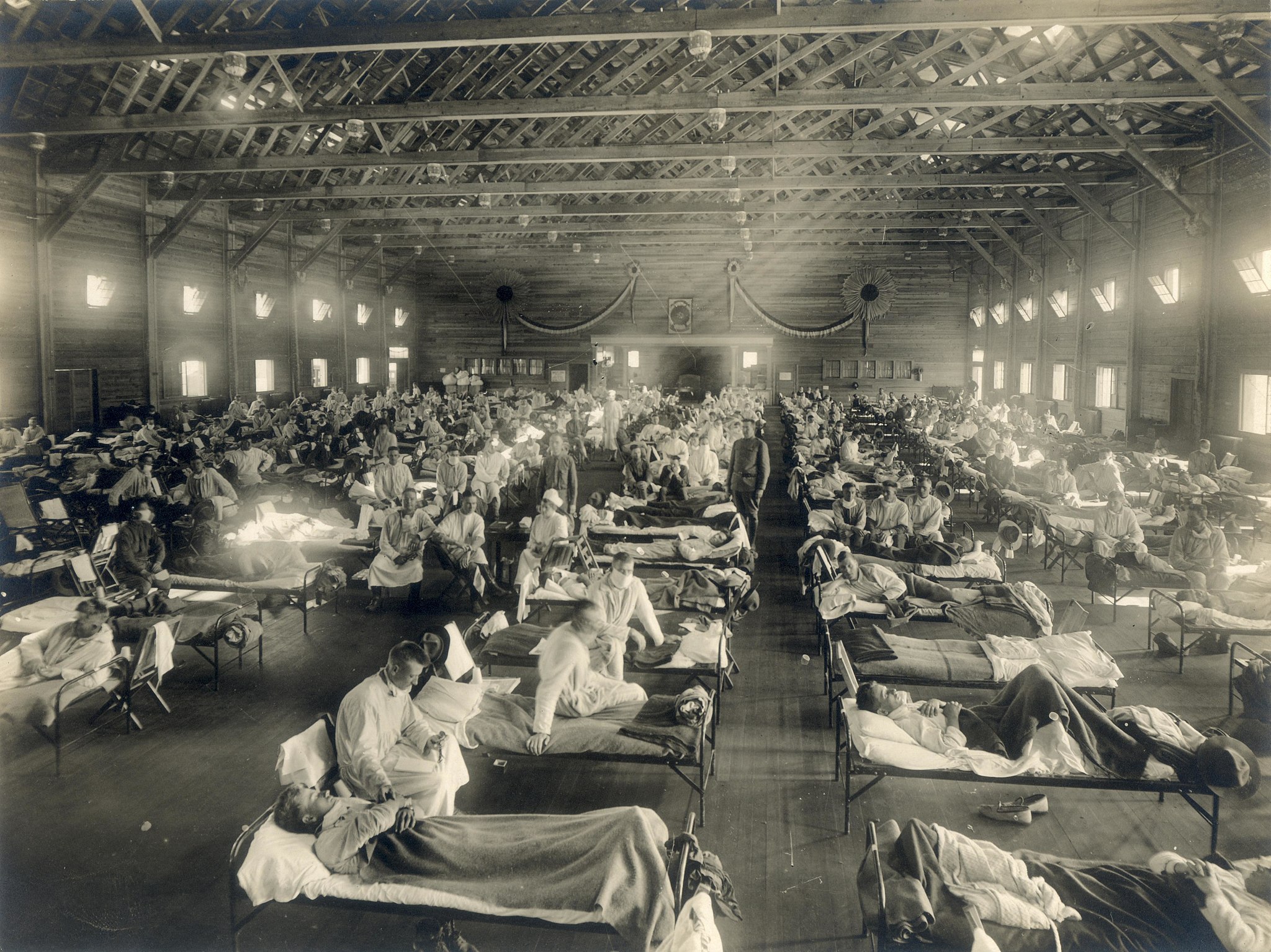

The second point that I think is important to convey is the catastrophic scope of the 1918 pandemic. Importantly, the pandemic was actually made up of two distinct diseases: a novel form of influenza and the bacterial disease pneumonia, which opportunistically attacked weakened hosts and was probably responsible for a majority of deaths. Most accounts suggest the pandemic began in the spring of 1918 at a military base in Kansas; it then spread across the United States and to Europe and Asia through the movement of military troops. The initial wave was relatively minor in terms of mortality. The second wave appeared in August 1918 in multiple locations, spread rapidly, and was far deadlier than the first. In the United States, the worst of it took place in October and November—in Philadelphia, for example, more than 11,000 people died in the month of October. The reasons for the increased mortality of the second wave are unclear but were probably the result of the virus mutating into a significantly more virulent form between the first and second waves. A third wave of the two diseases took place in the winter of 1918-1919 and, in some places, extended into 1920. In the United States, mortality rates reached an astounding 5 percent or more, and about 675,000 people died. Current estimates of total global mortality range from 20-50 million people or more, making the 1918 pandemic one of the deadliest disease outbreaks in human history.

Some scholars suggest that the high virulence of the disease meant that it killed indiscriminately, but this is not really accurate. The pandemic had an unusual pattern of age-specific mortality, for example, with atypically higher death rates among young adults aged 20-40 and lower death rates among older adults (a reversal of the usual pattern). The causes of this unusual distribution remain a mystery but may have been related to some developed immunity among older adults related to earlier exposure to the 1889 Russian influenza pandemic. The 1918 pandemic also appears to have impacted rural populations more heavily than urban ones, perhaps due to greater exposure in urban areas to other strains of influenza then circulating. Overall it appears to have affected the poor more heavily than other groups, although the debate about the issue is complex. This was probably at least partially a function of biology. As physician and historian Margaret Humphreys points out, the overall strength of the immune system can be depressed by malnutrition, fatigue, stress, and other factors. Some people were therefore more susceptible to the virus and to secondary pneumonia infection than others due to the conditions in which they lived. For these and other reasons, the social determinants of health played an important role in the distribution of mortality associated with the pandemic.

What are we to make of this catastrophe? Historians have written a tremendous amount about the 1918 pandemic, including widely read books by John Barry and Nancy Bristow. Historians sometimes make claims that are not well-supported from a scientific perspective (a point that is worth talking about with your students), and unless you are comfortable with the science you should probably be cautious about discussing technical details about how viruses behave. There are numerous resources available online about the pandemic and the history of disease more generally, including public lectures, documentaries, and a recent series of useful webinars hosted by the American Association of the History of Medicine organized in response to COVID-19. These resources should give you plenty of ideas about how the pandemic can be linked to other themes in your course. One important point to keep in mind is that epidemics act, as Charles Rosenberg puts it, as stress tests on societies, revealing their strengths, weaknesses, and contradictions in moments of crisis. Troop mobilization during World War I, for example, was clearly linked to the rapid spread of the disease and a good case can be made that the social disruption associated with the war led to increased immune-vulnerability among many groups. Whether or not this means that the war and the pandemic were “inextricably linked,” as Carol R. Byerly put it, is a matter of debate—among historians and perhaps also your students – but the connection between the two can be used to raise questions about globalization and vulnerability, national identity, the mobilization of public opinion in times of crisis, and numerous other issues.

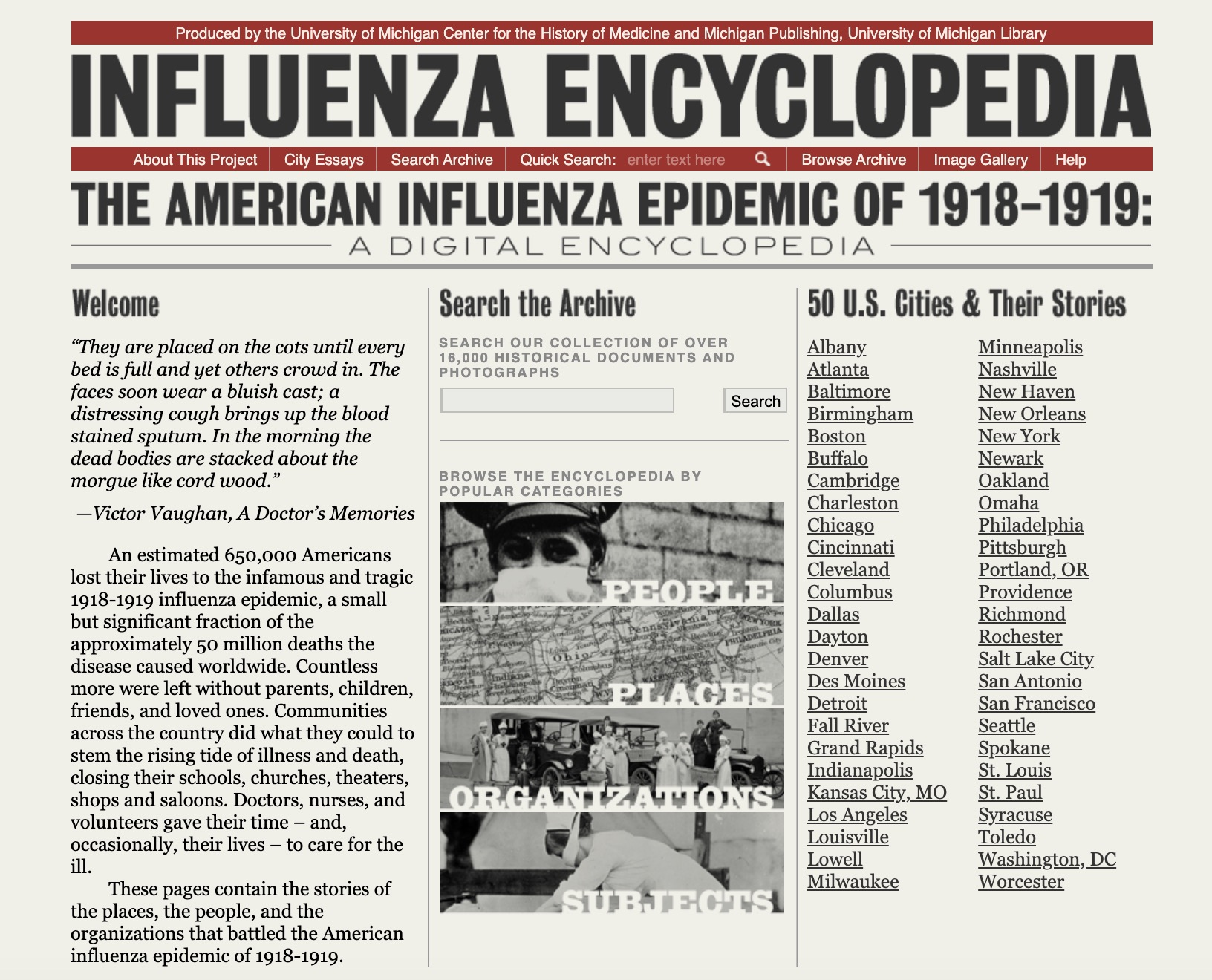

The scale and horror of the 1918 pandemic can be difficult for students to grasp. One useful approach is to examine the local impact of the pandemic on the histories of specific cities, institutions, or individuals and families that suffered. The University of Michigan’s Influenza Encyclopedia is particularly helpful in this regard; it includes narratives covering 50 cities and thousands of primary documents that can be used to explore the history of the pandemic in local contexts. A large number of secondary articles have also been written over the years detailing the effects of the pandemic in specific cities or regions. Depending on where you teach, archival material documenting the pandemic may be available that could be used as the basis for student research projects. A variety of diaries, letters, and other first-person narratives are available online and in hardcopy that can be used to examine individual people’s experiences. One of the points you might want to emphasize is that different people and communities were affected by the pandemic in ways that were both similar and different from one another. In my experience, emphasizing the diversity of experience during an epidemic can help students make sense of the fact that their own personal experiences may not directly conform to the patterns that they hear about in class. This is a particularly important point when discussing racial, gender, class, and other dynamics that shape the overall way epidemics play out but that may not be easily discernible when examined through the lens of individual stories. We need to be sensitive to the fact that our students’ experiences with COVID-19 are their own, even as we try to help them place these experiences in broader contexts.

More generally, the social determinants of health undoubtedly played a role in who lived and who died, although the way these determinants acted in racial and class terms is complex and open to debate. In Chicago, for example, deaths from influenza and pneumonia were highly clustered, disproportionately distributed among lower-income neighborhoods, correlated with illiteracy, and negatively correlated with home ownership (which in turn can be understood as a proxy for family wealth). It is worth asking your students why these types of correlations existed. Were the poor less likely to remain quarantined, and if so why? Were the illiterate less likely to follow public health advice? Why would the disease appear in geographic clusters rather than being spread through a city evenly? How did these dynamics play out in terms of race and class? These and other questions can be used to interrogate the unequal way the 1918 pandemic affected different communities, and they can be used to raise further questions about how and why COVID-19 is affecting different groups of people at different rates, most notably the differences between the young and old, racial disparities in mortality, and the fact that exceptionally high rates of infection take place in institutions such as prisons and nursing homes. COVID-19 is no more a “great equalizer” than was the influenza of 1918. Both pandemics, as David Jones has recently put it, “provide a sampling device for social analysis. They reveal what really matters to a population and whom they truly value.”

Dr. Joseph M. Gabriel

Joseph M. Gabriel is Associate Professor in the Department of Behavioral Science and Social Medicine and the Department of History at Florida State University. He studies the history of medicine, with a focus on the history of pharmaceuticals and the pharmaceutical industry. He is the author of Medical Monopoly: Intellectual Property Rights and the Origins of the Modern Pharmaceutical Industry (Chicago, 2014) and co-editor of Drugs on the Page: Pharmacopeias and Healing Knowledge in the Early Modern Atlantic World (Pittsburgh, 2019).